How Saladin united the Muslim forces to defeat the Third Crusade

Saladin rose to power as the Muslim leader who recaptured Jerusalem in 1187 and prevented its recovery by the Third Crusade.

He had spent years planning military campaigns, building religious authority among Sunni scholars and expanding his control across Egypt and Syria.

In 1187 he united fractured Muslim factions by forming alliances, restoring Sunni authority and calling for jihad, which prepared an organised response to the Crusader states.

Saladin's early life

Saladin, whose full name was Yusuf ibn Ayyub, was born in either 1137 or 1138 in the town of Tikrit, where his Kurdish family held a position in local military circles under Seljuk rule.

According to early sources, Zengi expelled Saladin’s family from Tikrit in the year of his birth, causing them to move.

His father, Najm al-Din Ayyub, and uncle, Asad al-Din Shirkuh, later served Zengi’s son Nur al-Din, who governed Aleppo and later Damascus.

The family soon moved to Baalbek and then to Damascus, which placed Saladin at the centre of military administration and political activity in the Islamic East at a time when Crusader attacks had destabilised much of the region.

During his youth in Damascus, Saladin received an education that reflected the expectations of a Sunni Muslim from a military household, which included Quranic studies, Arabic grammar, Islamic law, mathematics and some exposure to classical science and literature.

He likely encountered the teachings of the Shafi'i legal school. Early sources described him as reserved and inclined towards study, but Saladin gradually assumed more responsibility under the command of his uncle, whose campaigns in Egypt exposed him to the wider military challenges that faced the Muslim world.

Under Shirkuh’s leadership, Saladin participated in several expeditions into Egypt on behalf of Nur al-Din.

These campaigns aimed to reduce Fatimid influence and counter Crusader advances, and would give Saladin an important introduction to Egyptian politics and expose him to opportunities that would eventually lead to his control of the country.

Shirkuh remained the dominant figure during these expeditions, but Saladin’s presence at court and on campaign gave him a clear understanding of how to lead, how to organise a military and how to manage Sunni and Shi'a loyalties in Cairo.

Saladin's rise to power

Saladin’s rise began in earnest after the sudden death of Shirkuh in early 1169 and after the successful conclusion of a military campaign that had placed the Fatimid regime under Syrian influence.

Despite his relatively low rank and youth, Saladin was appointed vizier of Egypt with the approval of Nur al-Din.

His elevation also received formal endorsement from the Fatimid caliph al-Adid, whose support gave the appointment official standing but did not shield Saladin from resentment among Fatimid loyalists.

Many Egyptian elites initially viewed his promotion with suspicion, but he quickly strengthened his control by removing unreliable officials and replacing key administrators with men from his own ranks.

Within two years, he had ended the Fatimid Caliphate by ordering that Friday sermons in Egypt name the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad, which formally aligned the country with the Sunni order.

Though the transition occurred gradually, the 1171 khutba in the Abbasid caliph's name was the clear break.

This action satisfied Nur al-Din’s religious agenda and it presented Saladin as a leader of Islamic unity.

In the process, he had strengthened his hold on Egypt, had reorganised its army and the state's finances and military so that future campaigns could be launched with Egyptian resources and troops.

Following Nur al-Din’s death in 1174, Saladin marched into Syria, claiming that he aimed to protect the region from internal unrest and Crusader attacks.

Damascus accepted him without resistance, while other Zengid territories, including Aleppo and Mosul, held out for years.

At that time, Nur al-Din's son, al-Salih Ismail, technically inherited his domains but lacked the authority to maintain them.

Rather than rush into open conflict, Saladin used diplomacy, marriage ties, including one to Nur al-Din's widow, Ismat al-Din Khatun, whom he married in 1176, and some sieges to expand his authority.

The city of Aleppo only submitted to him in 1183, after long negotiations and military pressure.

By that year, he had brought most of Syria under his control, which created a power base that included Egypt, Hijaz and the Levant.

Saladin promoted the idea of jihad against the Crusader states as both a religious obligation and a political necessity.

His court included religious scholars such as al-Qadi al-Fadil and Imad al-Din al-Isfahani, who helped craft sermons, public letters, and proclamations calling for Islamic unity under his rule.

This messaging strengthened his claim to rule and also attracted volunteers and financial support from regions as far away as North Africa, Yemen and the eastern Islamic world.

How Saladin recaptured Jerusalem from the Crusaders

After he had secured his control over Egypt and Syria, Saladin began to prepare for a large-scale war against the Crusader states, whose internal weaknesses gave him an opportunity to strike.

By the mid-1180s, the Kingdom of Jerusalem had fallen into political disorder after the death of King Baldwin IV, whose successors lacked both popular support and military experience.

The influence of aggressive nobles such as Reynald of Châtillon, who defied truces by attacking Muslim trade routes and even threatened to raid the Hijaz, provided Saladin with justification to resume fighting.

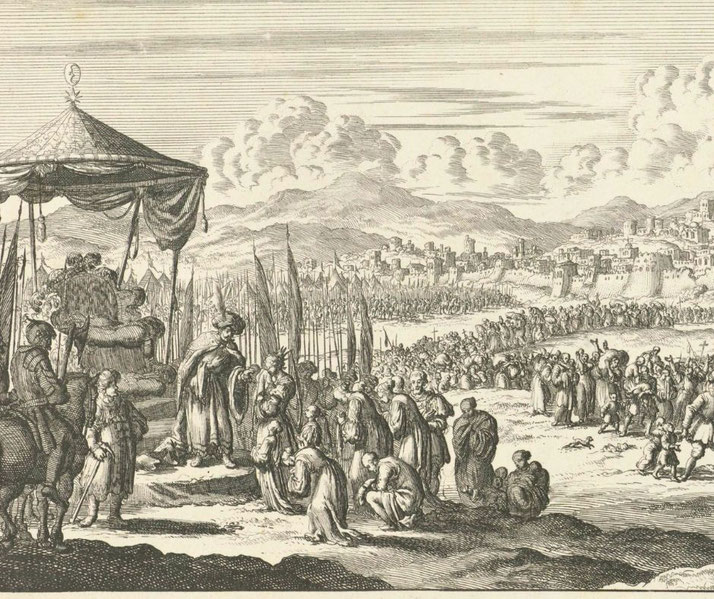

In 1187, he gathered a large force of Muslim soldiers from across his territories and marched north into the Galilee.

On 4 July, his army confronted the main Crusader host near the Horns of Hattin, where a combination of heat, poor water access, and tactical missteps led to the destruction of the Crusader army.

His forces, likely numbering between 20,000 and 30,000 men, surrounded and wore down the Crusader force, estimated at around 15,000, by cutting them off from Lake Tiberias and by lighting brushfires that worsened thirst and caused confusion.

Saladin captured King Guy of Jerusalem and executed Reynald of Châtillon for his repeated violations of peace.

The victory at Hattin destroyed most of the military leadership of the Latin Kingdom and left its cities defenceless.

Saladin used this collapse to launch a rapid campaign through Palestine, and he had taken Acre, Ascalon, Beirut, Sidon and Nablus in quick succession.

By late September, his army had reached the walls of Jerusalem, which now lacked both men and supplies to resist a prolonged siege.

After brief negotiations with Balian of Ibelin, Saladin allowed the city to surrender on 2 October.

He allowed Christian residents to leave after paying a ransom, and he allowed churches to continue to operate.

He also restored Muslim authority over sites such as the al-Aqsa Mosque, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre remained in Christian use under supervision.

The retaking of Jerusalem caused panic in Europe and undermined decades of Christian effort in the Holy Land.

In response, Pope Gregory VIII issued the papal bull Audita Tremendi, calling for a new Crusade to recover the city and halt Saladin’s advance.

Saladin and the Third Crusade

The Third Crusade brought an alliance of major European monarchs to the eastern Mediterranean.

King Richard I of England, King Philip II of France, and Emperor Frederick Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire all took the cross, though only Richard remained active for an extended period in the Levant.

After Barbarossa drowned in 1190 and Philip returned to France in 1191, Richard led most of the campaign.

Between 1189 and 1192, the conflict revolved around coastal strongholds and diplomatic disputes.

The long and bloody Siege of Acre ended in Crusader victory, and Richard won a major battle at Arsuf in September 1191, recapturing Jaffa and strengthening his position.

Despite repeated pressure, he failed to march on Jerusalem, in part because of concerns about stretching his forces too thin and holding territory in the interior without support.

Saladin, meanwhile, avoided large battles and focused on attacking Crusader supply lines, improving city defences and keeping morale up across his large territories.

In mid-1192, he attempted to retake Jaffa but was driven back by an unexpected counterattack led personally by Richard.

The two leaders, each unable to secure a final victory, eventually began direct negotiations.

Their views differed fundamentally, but both understood the limits of their campaigns.

Richard needed to return to Europe to secure his throne, and Saladin recognised the strain the long war had put on his troops and on his finances.

In September 1192, they signed the Treaty of Jaffa, which confirmed Muslim control of Jerusalem but allowed Christian pilgrims limited access to the city’s holy sites under agreed arrangements.

It also secured a fragile peace along the coast, where the Crusaders retained a corridor between Tyre and Jaffa.

The treaty concluded the Third Crusade without resolving its central question, the status of Jerusalem, but it constituted an important victory for Saladin.

He retained the city, maintained control over most of Palestine, and prevented further Western advances into his territory.

Saladin's death and legacy

Saladin died in Damascus on 4 March 1193, just a few months after the treaty with Richard came into effect.

His health had deteriorated from years of continuous campaigns, and his final illness left him bedridden.

He had ruled over extensive lands and commanded large armies, but he had given most of his personal wealth to the poor and to his soldiers, leaving only a few dinars and possessions at the time of his death.

His funeral attracted a large crowd in Damascus, where religious leaders praised his commitment to Islamic unity and generosity.

Historians noted that he had spent more on charitable donations than on luxuries and that his rule had brought stability after decades of conflict between rival dynasties.

He was buried in the Garden of the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus. In 1898, German Emperor Wilhelm II visited his tomb and paid for a new marble sarcophagus to honour his memory, which was placed beside the original wooden one.

In the years that followed, his empire fell apart among his relatives, as none of his sons or brothers could match his skill at balancing command of the army with political administration and the management of religious affairs.

Saladin’s memory endured across the Islamic world. Sunni historians wrote admiringly of his piety, praised his humility and recorded examples of his justice, and even Christian sources praised his chivalry and conduct during warfare.

Mosques, schools, and charitable foundations continued to bear his name centuries after his death.

In modern Arab nationalism, especially during the 20th century, Saladin became a symbol of unity and resistance against Western control.

As a result, his example still affects how political and military leadership is remembered in both Islamic and global historical traditions.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.