Why were Roman soldiers given crowns?

In ancient Roman history, soldiers were awarded crowns as formal honours that were considered to be concrete rewards that recognised specific acts of courage, but they also carried immense social and political value, which affected a soldier's social standing.

Soldiers who received them often raised their status outside the battlefield, earning increased influence and respect in both military and common life.

Understanding Roman military culture

In the strict structure of the Roman military, most ranks had a defined role, and most soldiers understood the consequences of disobedience or cowardice.

Punishments for failure could include fines, demotion, public humiliation, or execution, while success often led to promotion, greater pay, and public honours.

As such, training often focused on building strict discipline, and commanders expected their soldiers to carry out orders exactly, even in the most desperate circumstances.

Because of this, virtus, a Roman ideal that combined bravery with loyalty and martial skill, came to be the measure of a soldier’s worth.

Soldiers who distinguished themselves in battle often did not remain anonymous.

Individual heroism could be remembered through the award of a crown.

Battlefield honours offered a concrete way to reward those who placed the needs of the Republic or Empire ahead of their own.

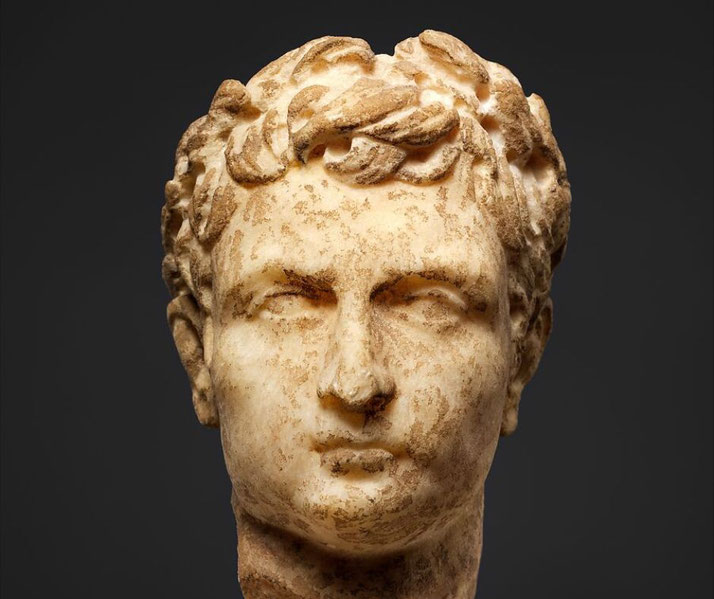

Veterans who had received these crowns often displayed them in public portraits, carried them in victory parades, and mentioned them in their political campaigns.

To illustrate, election notices from the late Republic sometimes included references to a candidate’s military awards.

In a society that valued proven loyalty to the state, these decorations opened doors to public offices and Senate membership.

The visibility of such honours often reinforced the values that bound Roman society together, from the frontlines of distant provinces to the steps of the Capitol.

Evidence from coins and inscriptions shows how commanders often used these images to advertise military honour to the Roman people.

What crowns could a soldier earn?

Romans created a highly specific system of military crowns, each with its own name, material, and rules.

Soldiers who saved the life of a fellow Roman in battle could receive the corona civica, or civic crown, which was made of oak leaves and required sworn testimony from the man whose life had been saved.

Recipients earned the right to wear the crown at public events and to receive a standing ovation when they entered the theatre, because the honour elevated the soldier’s status for life.

The corona civica required sworn testimony by the man who had been saved and often by fellow soldiers, which provided a public proof that reduced false claims.

For those who took the greatest risks during sieges or assaults, the mural crown (corona muralis), which resembled the battlements of a city wall, was awarded to the first man to climb the enemy’s walls during an assault.

Its naval counterpart, the naval crown (corona navalis), bore designs of ship prows and was given to the first soldier to board an enemy vessel during a sea battle.

Each of these crowns had high status, but they recorded a soldier’s willingness to enter the most dangerous position in battle, where survival was uncertain and failure was often fatal.

Even then, one award stood above the rest. The corona graminea, or grass crown, was made from grasses and plants gathered from the battlefield and held the highest distinction.

Unlike other decorations, which generals or commanders bestowed, this one could only be granted by the soldiers themselves to a commander who had saved an entire army from destruction.

That made its symbolism even stronger. The men whose lives had been spared confirmed with their own hands that their general had earned the highest honour Rome could bestow.

As a result, the corona graminea remained exceptionally rare. Ancient authors had treated it as almost unique and had recorded only a handful of cases.

Other crowns included the corona aurea, or golden crown, which could be awarded for acts of general bravery.

It was not restricted to battlefield feats and could also recognise important civic deeds.

Officers sometimes received custom crowns to recognise specific accomplishments, such as an officer who negotiated an enemy’s surrender, who rescued a standard, or who defended a vital position.

Their designs changed with the situation of the award. However, their purpose stayed the same: each preserved the memory of sacrifice and rewarded those who risked death to uphold Roman power.

Ancient authors who described these honours included Livy (Ab Urbe Condita), Valerius Maximus (Factorum et dictorum memorabilium libri IX), and Plutarch for Republican examples, as well as Cassius Dio (Roman History) for later Imperial accounts.

Suetonius primarily focused on imperial biographies and courtly anecdotes and occasionally referenced ceremonial honours but offered limited detail on military crowns themselves.

These sources have allowed modern readers to trace how crowns also acted as signs of political influence and personal honour rather than just as military awards.

Why were these crowns so important to Romans?

The Roman state encouraged others to act firmly through rewards that recognised individual bravery in visible ways.

It also tied personal courage to the safety and strength of the collective. The soldier who saved a comrade or captured a vital position acted for the Republic or Empire rather than for himself.

His reward demonstrated that such sacrifices would never be ignored.

In fact, Roman honour was often expressed in public space, as most triumphs, inscriptions, and ceremonies aimed to show the citizens what values their state upheld.

The state often indicated that his conduct deserved admiration and imitation when it gave a man the right to wear a crown in the forum or theatre.

However, practical benefits often accompanied these symbols. Recipients of the corona civica, for example, gained exemptions from some taxes and duties, and they could attend public games in reserved seats.

Their families shared the honour, because sons and grandsons could mention the decoration in speeches or funerals.

On tombstones, the crown might appear in sculpture or text, which ensured that the honour would not be lost with time.

Roman families valued family reputation and used these military awards to establish a noble reputation that shaped future political careers.

The man who wore the crown became more than a decorated veteran because he was proof that Rome rewarded service, protected its values, and remembered its heroes.

Even centuries later, those accounts often continued to influence Roman ideas about duty and sacrifice.

Although, modern historians have debated whether crowns were primarily used genuine military rewards or as tools of political propaganda, and many accept that they served both functions at different times and for different figures.

Some very famous recipients of these crowns

Throughout Roman history, several individuals earned military crowns under circumstances that became famous.

Publius Decius Mus was active during the Latin War (c. 340–338 BCE) and performed the ritual of devotio by dedicating himself to death in order to secure Roman victory.

His intentional sacrifice, which was carried out in full view of both armies, became a symbol of virtuous death in service to the state.

Ancient sources do not state that he received the corona graminea, although later traditions associated his name with the highest ideals of Roman heroism.

Livy described the event in detail in Ab Urbe Condita Book 8.

Lucius Cornelius Sulla won honours during the Social War (91–88 BCE), which later helped his rise in the 80s BCE.

His early military achievements, such as the capture of key enemy positions, earned him the loyalty of the legions and the admiration of the Roman electorate.

Valerius Maximus included accounts of his decorations in Memorable Deeds and Sayings.

More famously, Pompey and Julius Caesar used military honours and imagery during their late-Republic careers (1st century BCE) to bolster public support.

Both men included symbolic crowns in their triumphal processions and sometimes featured crown motifs on their coinage.

While such depictions often drew on broader symbols like laurel wreaths rather than specific military crowns, their efforts to align themselves with older martial traditions strengthened their claims to leadership during a time of political upheaval.

Trajan’s Dacian campaigns (101–106 CE) produced victory images that included references to crowns and that appeared on monumental arches and coins.

These images reinforced the idea that the emperor possessed the same courage and command that older Roman generals had displayed.

Cassius Dio recorded the Senate's formal recognition of Trajan’s military conduct in Roman History Book 68.

The important ceremony when giving a crown

The presentation of a military crown often took place in front of the assembled army.

The commanding officer would describe the deed that had earned the award.

Witnesses, who sometimes included soldiers who had been rescued or defended, confirmed the details, and then the recipient stepped forward and accepted the crown in full view of his peers.

The crowd applauded, and the man’s name became known throughout the ranks.

At other times, especially in Rome, when the Senate granted a crown, the ceremony occurred in more public spaces.

Recipients might appear in theatres, forums, or during triumphs. Often, the citizen audience already knew the story behind the award.

To strengthen the authority of the award, ceremonies often included religious elements.

For examples, animals were sacrificed on altars, and prayers were made to the gods.

Even under the Empire, when the process became more formal and symbolic, the structure of the ceremony still followed the traditional pattern.

The army gave its approval, the commander gave his praise, and the gods received their due.

Regardless of the exact ceremonial structure, the moment reminded the audience that Rome owed its strength to those who risked their lives for its cause.

That crown, whether made of grass, oak, gold, or bronze, turned one man’s action into a symbol of the Republic’s values and connected personal sacrifice to national memory to ensure that neither would be forgotten.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.