How the engineering marvel of the Roman roads built an empire

Roman roads supported the expansion and stability of one of the largest empires in ancient history. As an extensive and long-lasting network of routes stretched from Britain to the Euphrates frontier, Roman authorities enabled faster communication and more efficient troop movements while boosting economic activity.

How the network of Roman roads developed

During the early Republic, Roman roadbuilding began as a planned response to military challenges.

In 312 BCE, the censor Appius Claudius Caecus ordered the construction of the Via Appia to connect Rome with Capua, which established the first major paved route.

It later enabled rapid troop movement during the Third Samnite War. Over time, new roads followed as consuls, censors, and emperors sponsored further projects that improved movement across the Italian peninsula and into the provinces.

In many cases, engineers adapted old local tracks to match Roman standards of design and structure.

As new territories came under Roman control, officials focused on routes that linked military garrisons with cities, ports, and government centres.

Local labour contributed to these efforts, often under the direction of magistrates who ensured quality and consistency.

During the reign of Augustus, the system expanded rapidly, though the full extent of over 80,000 kilometres was achieved later in the Imperial period.

Surveyors used a groma to align roads with accuracy, and they laid out direct lines that crossed mountains, forests, and rivers.

At regular intervals, milestones recorded distances and sometimes listed the names of the builders.

In addition, relay stations and rest houses provided support to messengers, merchants, and officials who travelled for business or command.

How were Roman roads made?

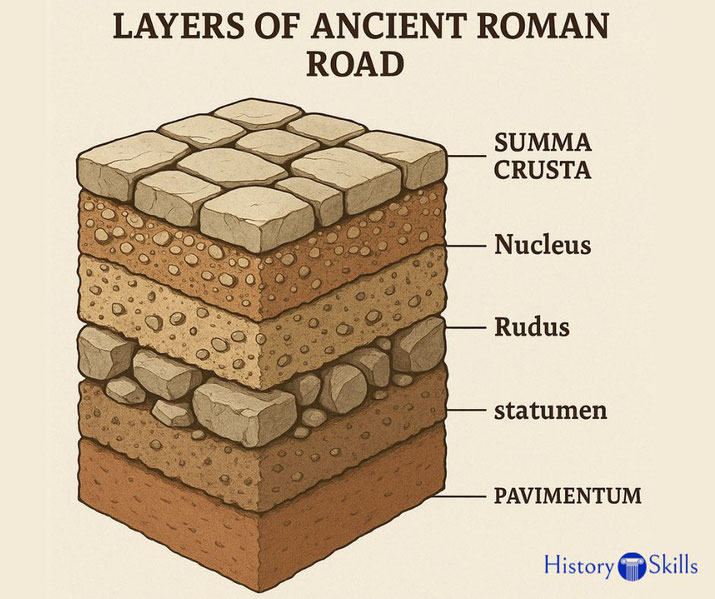

Roman engineers followed a step-by-step method designed for durability. The process began with the digging of a trench along the chosen route.

Next, workers laid the statumen, a foundation of large stones, followed by the rudus, which contained gravel and lime to strengthen the surface.

Then came the nucleus, a pressed layer that supported the final surface, the summum dorsum, made of flat paving stones fitted together tightly.

Builders shaped the surface with a slight arch to channel rainwater into side ditches.

On some roads, kerbstones bordered the edges to protect the structure from wear and collapse.

Skilled labourers worked under the supervision of appointed civic officials or, in frontier zones, military engineers.

In newly conquered areas, Roman soldiers often performed the work themselves, especially where urgency required immediate road access.

In regions where volcanic stone or high-quality gravel was unavailable, builders used whatever durable materials they could quarry nearby, such as limestone or sandstone.

Main highways typically spanned four to six metres in width. In some areas, roads included passing points, raised footpaths, and wheel ruts worn smooth from years of use.

Roads could be up to 1.5 metres deep from the foundation to the surface. Bridges and culverts carried the system across rivers and marshes, while stone embankments supported roads cut into hillsides.

Over time, this engineering expertise created the most advanced road system of the ancient world.

Famous Roman roads

The Via Appia, which we mentioned above, remained the most famous of all Roman roads.

Connecting Rome to Brundisium, it played a major role in troop movements and trade with Greece and the eastern Mediterranean.

Latin writers praised its straightness, reliability, and symbolic value to the Roman psyche.

But it was not the only main road in the empire. The Via Flaminia ran northeast from Rome to Ariminum and opened access to the Adriatic coast.

It was essential during military campaigns in northern Italy and remained a key transport corridor well into the imperial period.

Also, the Via Aurelia ran toward Pisa and continued past it, linking the capital with coastal Etruria and Liguria.

Another important route, the Via Domitia, connected the Italian peninsula with Hispania.

It was commissioned in 118 BCE under Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, and it ran across southern Gaul and enabled fast communication with western provinces.

In the Balkans, the Via Egnatia allowed troops and traders to travel from the Adriatic coast to the Hellespont, with onward passage by sea to Byzantium.

Throughout the Empire, stone milestones marked each Roman mile. Some included inscriptions naming emperors or governors who funded repairs.

Others featured directional markers or references to military units involved in construction.

In the Forum at Rome, the milliarium aureum that was erected by Augustus in 20 BCE, reminded citizens that all roads, no matter how distant, ultimately led to the capital.

What was it like to travel on a Roman road?

Travel along Roman roads varied widely according to social status and financial means.

Imperial couriers and officials used the cursus publicus, a government-run transport system with access to fresh horses and safe waystations.

Wealthy individuals travelled in covered carriages, often accompanied by slaves and porters who carried their baggage and provisions.

Along the way, inns and mansiones offered meals and rest, although the quality of the comfort they provided tended to range greatly.

Some provided clean bedding, food, and places to wash and rest, while others suffered from poor upkeep and dishonest innkeepers.

Travellers planned their journeys in stages based on known distances between towns and roadside stops.

In some provinces, travel could be fast during the dry season. A courier who used the cursus publicus covered up to 80 kilometres in a single day.

However, in regions with poor drainage or heavy rainfall, roads became blocked for carts.

Travellers risked accidents, delays, and attacks from bandits in remote areas. To reduce danger, some groups travelled together or paid for armed protection.

Ancient guidebooks and route maps helped prepare for long journeys. The Itinerarium Antonini, compiled under or after the Antonine period, listed stations and distances, while the Tabula Peutingeriana showed simple road layouts that included cities, rivers, and main landmarks.

Pliny the Elder also wrote about Roman roads, praising their engineering and reach.

With the help of these tools, travellers could generally navigate across great distances with confidence.

Why the roads were so important to the Roman army

The army depended on reliable roads to move legions, supplies, and messengers quickly across the Empire.

Without permanent roads, defending distant provinces, launching organised attacks, or stopping local revolts would have been impossible.

This is because troop movements required speed and predictability, especially in unstable frontier regions.

As we mentioned before, Roman engineers often built roads as part of their military duties.

On campaign, legions carried tools and materials to build roads on the march.

Once peace came, permanent roads replaced temporary tracks. Defended supply depots and watchtowers also appeared at intervals along major routes to protect travellers and keep use going.

Garrison towns depended on these routes to receive grain, weapons, and reinforcements.

Most importantly, toads enabled the swift transfer of orders from central command to remote units, so governors and generals used them to deliver tax payments and coordinate defence movements among the troops.

In some writings, military units received formal credit for roadbuilding. On boundary stones and triumphal arches, emperors often claimed public recognition for expanding or restoring major routes.

During Caesar’s Gallic campaigns, legions built or improved roads to enable rapid repositioning across hostile territory.

In every case, the road system formed the backbone of Roman military strength.

Why the roads fell into disuse

In the later Empire, economic pressures and administrative decline reduced road upkeep.

As tax revenues fell and internal disorder increased, many provinces no longer repaired roads.

In some cases, roads remained in use but suffered from erosion, flooding, or damage.

After the collapse of the Western Empire in 476 CE, later kingdoms took over the road network but lacked the funds and engineering knowledge to maintain it.

In regions such as Gaul or Hispania, only certain roads continued to serve local trade or pilgrimage.

The Via Egnatia, for example, saw continued use by Byzantine forces and Christian travellers.

Others disappeared under overgrowth or became footpaths used by shepherds and villagers.

In addition, changes in settlement patterns reduced demand for overland routes.

As towns shrank or shifted, old roads no longer served vital purposes. Sea-based trade grew, and rivers offered safer and cheaper transport for bulk goods.

Over time, maintaining roads no longer justified the cost for small, fragmented polities.

Nevertheless, many Roman roads remained partly intact. Some appeared on medieval maps and guided merchants or pilgrims toward religious centres.

The Via Francigena, a pilgrimage route from Canterbury to Rome, followed parts of the ancient system.

In several cases, modern highways follow the original routes. Although the Empire collapsed, the physical remains of its roads continued to shape travel and trade long afterward.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.