The enigmatic mystery religions and secret societies of Ancient Rome

In ancient Rome, religion generally governed public and private life through official rituals and state-funded temples, which provided public ceremony that affirmed loyalty to the gods and the city.

Yet beneath this civic structure, there existed a separate religious world of secretive cults and foreign rites that promised personal change and offered secret knowledge or salvation to followers.

Many of these underground movements attracted devoted followers, which often provoked suspicion from Roman authorities.

Traditional Roman religious beliefs

The earliest Roman religion primarily consisted of practical rites that aimed to gain the gods' favour through public worship and visible sacrifices that included the reading of omens.

Rituals generally followed strict patterns and maintained what the Romans called pax deorum, or "peace with the gods," a state in which correct performance of ceremonies secured the city's prosperity and military success, preserving social harmony.

Officials such as the pontifices, augures, and flamines often regulated these rites and interpreted divine will, which supported the state's authority and tied that authority to divine favour.

Festivals like Saturnalia for Saturn, Lupercalia for fertility, and Vestalia for Vesta, which regularly punctuated the sacred calendar, highlighted public religious life.

Importantly, Roman religion generally emphasised visible action combined with correct procedure, supported by ongoing community practice instead of belief in sacred texts or doctrines.

Temples typically stood in the centre of towns and forums, from which processions often celebreated important feast days on the calendar.

Sacrifices occurred in the open, often accompanied by prayers spoken in fixed Latin forms to ensure consistency with past practice.

The gods, who typically each held defined responsibilities such as Jupiter for the skies, Mars for warfare, and Vesta for the hearth and home, did not offer personal salvation or a personal relationship with the gods.

As Roman power expanded across the Mediterranean, the state gradually absorbed deities from conquered regions and adapted them to Roman ways, and so Greek gods were given Latin names and adapted to Roman custom.

Yet even adopted deities fell under the supervision of Roman officials and became part of public cults.

For that reason, any group that introduced foreign rites outside this pattern often seemed to threaten public order.

Why were Romans suspicious of secret societies?

Romans generally expected religious practice to occur under public supervision.

When groups met in secret, performed unfamiliar rituals, or refused to name their gods, officials frequently viewed them with serious suspicion.

This is because public religion reinforced Roman identity, which meant that private worship that had avoided the state had often threatened the system that tied divine will to civic order.

Therefore, magistrates drew upon older laws, such as the leges de collegiis, to regulate or prohibit gatherings they deemed disruptive.

Religious secrecy made groups seem politically disloyal because Roman religion operated as part of state affairs and any unsanctioned assembly could often resemble a conspiracy.

Since senators had recalled past uprisings that had begun under the cover of religious or fraternal meetings, magistrates often investigated underground cults and asked whether loyalty to the emperor had been compromised.

Cicero and Tacitus both expressed concern over rites conducted in darkness or isolation, fearing that such acts hid plots against the state.

Under Roman law, magistrates could sometimes prohibit religious groups from gathering, especially if they used foreign rites or gathered at night.

If the cult involved blood sacrifice, initiations, or ecstatic behaviour, the Senate might issue a decree banning the rites outright.

At the same time, Roman law did not always persecute new beliefs. The fear often came from the secrecy and from the belief that such groups weakened discipline and public morality, eroding civic loyalty.

1. Cult of Cybele and the Galli

The cult of Cybele first gained Roman attention during the Second Punic War.

The Senate had consulted the Sibylline Books in 204 BCE and had received a prophecy that instructed them to import the goddess from Phrygia to help defeat Hannibal.

So, her sacred black stone, the symbol of the Great Mother, was brought to Rome and placed in a temple on the Palatine Hill known as the Temple of Magna Mater.

Once established, Cybele's rites surprised many Roman observers. Her priests, who were known as the Galli, engaged in intense displays of devotion that involved loud drumming and energetic dancing that included dramatic acts of submission to the goddess.

Ancient sources describe ritual self-castration, colourful robes, and feminine hairstyles and jewellery, though much of this account often shows upper-class Roman disapproval rather than precise documentation.

The self-castration ceremony reportedly took place during the Megalesia festival in March, when religious fervour peaked.

Although Cybele had been officially welcomed into the city, the Senate restricted the full expression of her rites.

Citizens could honour the goddess publicly but were generally prohibited from joining the Galli or participating in their more extreme rituals.

Foreigners and slaves largely became her primary followers. Therefore, the cult had two roles: it received official ceremonial welcome but largely remained at the edges of official religion because of its foreign origins and ecstatic rites.

Attis, who was her consort, had a story that often added an emotional and mythic element to the cult's theological appeal.

2. Mithraism

Mithraism offered Roman men, especially soldiers, a form of personal religion that emphasised discipline that demanded loyalty and promised an eternal reward.

Originating from a Persian god reimagined within Roman beliefs, the cult of Mithras grew during the 1st and 2nd centuries CE and spread rapidly throughout military garrisons across the empire.

Worship typically occurred in small underground chambers called mithraea, which provided the darkness and privacy needed for secret rites.

Archaeologists have discovered to date more than 400 mithraea, with examples at Ostia, Londinium, Carnuntum, and beneath the Baths of Caracalla.

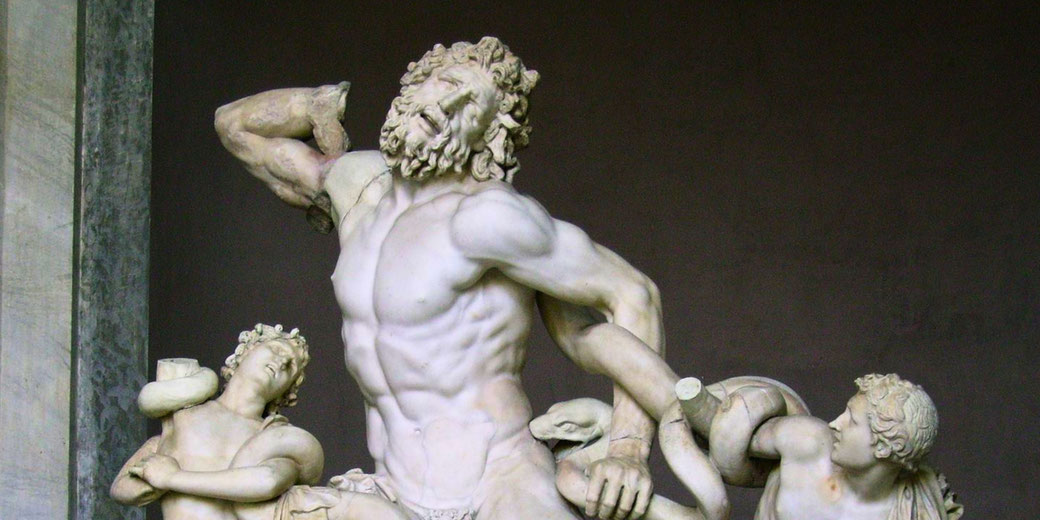

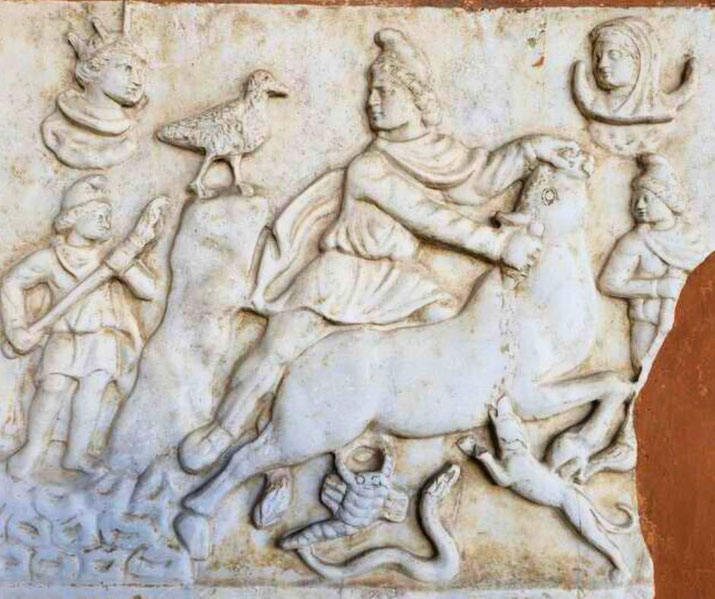

Each mithraeum featured a carved relief showing Mithras slaying a bull. Known as the tauroctony, this image held symbolic meaning known only to initiates.

Members passed through a series of grades, which began with Raven and then continued through Nymphus, Soldier, Lion, Persian, Heliodromus and finally Pater.

The precise order and function of these grades varied regionally, but each stage involved ritual tests and symbolic meals that reinforced group loyalty and gave members a sense of spiritual renewal.

Because of its secrecy and exclusion of women, the cult remained largely hidden from public life.

However, it appealed strongly to the military, where hierarchical discipline mirrored the cult’s structure.

Roman authorities rarely interfered with Mithraic groups because the cult encouraged obedience and self-restraint, which fostered courage, and so Mithraism thrived in the shadows of Roman cities and operated quietly alongside more visible religious traditions.

3. Cult of Isis

The cult of Isis entered Roman life from Egypt and became one of the most widely practiced foreign religions in the empire.

Isis often offered personal protection, healing, fertility, and the promise of life after death.

For those excluded from Roman public religion, especially women, freedmen, and merchants, her worship often provided meaning and inclusion.

The Iseum Campense, which was a major centre of worship, stood near the Campus Martius in Rome.

Temples to Isis frequently appeared in key port cities. Ceremonies involved processions with music and incense that accompanied water purification rites and detailed prayers to the goddess, who was praised as the "mother of the universe."

Her followers typically wore white linen and generally observed a period of ritual silence before sunrise, when they would greet the rising sun in honour of Isis’ connection to rebirth.

Apuleius’ novel The Golden Ass provides one of the more detailed literary accounts of Isis initiation rites, though the narrative uses symbolic storytelling and a literary style rather than precise ritual instruction.

Since Roman emperors frequently viewed her cult with suspicion, Augustus, Tiberius, and others banned Isis worship from Rome at different times.

Accusations against her followers often included superstition, immoral rites, and dangerous influence over the lower classes.

Yet the cult later returned under later emperors and flourished during the 2nd century CE.

It spread from Spain to Syria, and even members of the imperial household showed devotion to Isis. Emperors like Caligula personally supported the cult, and Hadrian built shrines to Isis and Serapis.

Her popularity grew because she offered care that gave people identity and a promise of spiritual renewal in ways Roman state religion did not.

How the Romans tried to suppress these groups

When religious groups appeared to disrupt public order or contradict Roman authority, the state often used legal and military force to eliminate them.

The most famous example occurred in 186 BCE when the Senate moved to suppress the Bacchanalia.

This cult was dedicated to Bacchus (Dionysus) and had reportedly attracted thousands of followers across Italy.

An informant named Hispala Faecenia had revealed its secret rites, which allegedly included sexual misconduct, forged documents, and plots against Roman families, so the Senate reacted swiftly and ordered arrests, interrogations and executions.

According to Livy, many people faced charges, and a significant number were executed.

Later sources and modern estimates have sometimes suggested thousands were involved, but the exact number remains uncertain.

The Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus made it illegal to hold Bacchic rites without express permission.

No more than five people could gather at a time, and a praetor had to approve the meeting.

The Senate then dismantled temples and published inscriptions throughout Italy to make the new law known.

One such inscription survives from Bruttium in southern Italy.

Over time, other groups also gradually faced restrictions. Astrologers, Druids, and foreign priests were sometimes expelled under Claudius and later emperors.

The justification generally rested on maintaining public order and protecting Roman values.

Because the state accepted religious variety only if the rites supported Roman rule and reinforced public morality, anything that undermined loyalty to the emperor or operated outside the law met swift suppression.

At times Augustus banned druidic rites, and Claudius targeted both astrologers and Egyptian cults.

Was early Christianity a mystery religion?

At first, early Christianity resembled the mystery religions that Romans already feared.

Converts joined small house churches, underwent secret rites such as baptism, and gathered before dawn to share sacred meals and sing hymns to Christ.

They refused to honour Roman gods or offer sacrifices to the emperor, and so Roman officials viewed them as refusing to conform, disloyal and potentially dangerous.

Pliny the Younger wrote a letter around 112 CE in which he described Christian gatherings in Bithynia, in which he explained that the members swore to avoid theft, adultery, and dishonesty, and then dispersed until they met again for food.

Although he found no criminal behaviour, he recommended punishing them because of their defiance and secrecy.

Emperor Trajan responded by advising moderation: Christians were to be spared from being hunted and were to be punished if accused and remained unrepentant.

As persecution increased, Christians developed written texts, defined doctrines, and established leadership structures that set them apart from the cults around them.

Still, they retained some mystery religion traits. Initiation, sacred meals, secrecy, and a promise of eternal life remained central to the faith.

However, Christianity originated in a monotheistic Jewish tradition and developed theological doctrines that distinguished it clearly from the mystery cults.

Defenders such as Justin Martyr and Tertullian wrote defences against Roman accusations of secret plotting.

Because Christianity had become legal and had begun to receive state support after Constantine’s conversion and the Edict of Milan in 313 CE, over the next century it gradually replaced many competing cults, sometimes absorbing their temples, festivals and ritual language into its growing religious organisation.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.