How to feast in ancient Rome: The dos and don'ts when attending a Roman dinner party

Among the carefully tiled courtyards, painted walls, and perfumed air of a wealthy Roman domus, the dinner party was a central event in elite Roman life.

Known as a cena, this evening meal brought together guests for entertainment and conversation in order to display status.

An invitation to such an event implied a level of honour, and it carried with it a set of expectations that needed careful attention.

Those who misunderstood the unwritten rules of behaviour risked embarrassment or exclusion from future gatherings.

The first things you need to know about Roman feasts

In Rome’s wealthier households, the dinner party held a key role in keeping social connections and showing one’s elegance.

The cena usually began in the late afternoon, often around the ninth hour, approximately 3 pm, and could last for several hours.

This timing showed developments of the Imperial period, since in earlier Republican times, the main meal occurred closer to midday.

It focused on showing status through a luxurious setting, varied courses and matching entertainment.

Wealthy hosts used such occasions to affirm their position within the Roman elite by inviting clients, business partners, politicians, and influential acquaintances.

The host’s aim was to impress and to forge or strengthen connections. Historical figures such as Lucullus became famous for their lavish banquets, which could feature as many as seven courses of food.

Guests were arranged according to social rank, and seating followed strict rules known as the ordo.

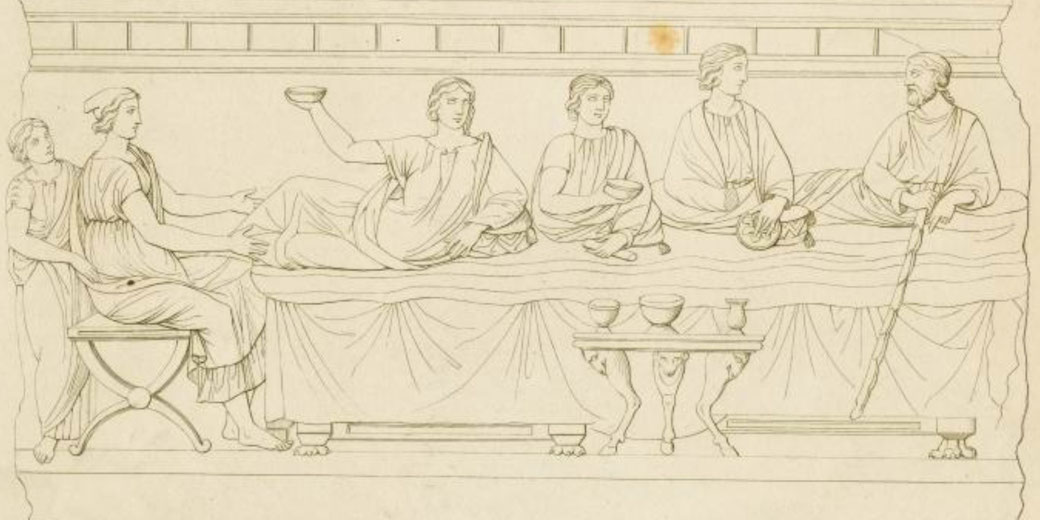

The dining room, or triclinium, contained three couches arranged around a low table, with each couch holding three people who reclined on their left elbows.

The most honoured guest was placed in the central position of the central couch, known as the locus medius.

Slaves attended to the needs of each guest, who brought food and drink and who sometimes helped with handwashing.

These slaves had special roles: structores carved the meat, aqua venatores poured water, and nomenclatores announced the names of arriving guests.

While handwashing slaves were less commonly named in sources, their role in keeping things clean was nonetheless important.

Everyone present was expected to know their place within this structure, and any disruption to the established order would have been noted as an insult or an error of manners.

How to prepare yourself for dinner

Before attending a cena, invited guests typically bathed and dressed in their finest available clothes.

For men, this often meant wearing a clean white tunic, while senators or high-status guests might wear a toga.

Women selected elegant stolas or tunics, often decorated with tasteful jewellery and scented oils.

When guests bathed at the public baths before the feast, it was considered polite because it showed respect for the host and the other guests.

In some cases, the host might provide perfumes or even slaves to help guests clean up on arrival.

It was also important to arrive at the right time. If guests turned up too early, it suggested greed, but arriving too late might mean missing the best parts of the meal or disrespecting the host’s efforts.

Guests often brought along their own napkins, which they used during the feast and sometimes even to take food home, though this was only suitable under certain situations and depended on one’s status and relationship to the host.

In earlier periods of the Republic, it was not unusual for women to be excluded from such gatherings entirely.

What to expect when you arrive

Upon arrival, guests were typically greeted by a slave and sometimes by the host himself, especially if the guest held a higher social rank.

The atrium of the house might be decorated with garlands or incense, and a doorkeeper would record names or provide directions.

Entering the house was an event in itself, and the layout often reinforced the power and wealth of the host.

Mosaics, statues, and painted frescoes offered visual signs of host's culture. Some homes featured running water, bronze fittings, or small fountains, all designed to impress.

Once led into the triclinium, guests were directed to their assigned places. A light course of appetisers, known as the gustatio, usually began the evening, often accompanied by mulsum, a sweet wine mixed with honey.

Entertainment such as musicians, singers, poets, or dancers might perform during this first stage.

On rare occasions, acrobats or mime actors provided more rowdy performances.

The nature of the dinner determined whether conversation focused on politics, philosophy, poetry, or recent gossip.

Guests were expected to contribute to the atmosphere but avoid speaking too much, especially if of lower status.

Knowing how to engage without overstepping boundaries was an important social skill.

The most important dining etiquette to know

Correct posture was essential. Sitting upright was considered rustic or undignified.

Reclining while dining had been adopted from Greek customs and was associated with freedom and citizenship; slaves and those of lower class were expected to eat seated or standing.

Guests who spoke as they chewed were frowned upon, and they were expected to eat neatly, using their fingers or a spoon.

Knives were rarely needed by guests, as the food was often pre-cut by the structores, though hosts did employ knives for preparation and serving.

Cleanliness was important, and bowls of water and towels were often provided for guests to clean their hands between courses.

Conversation needed to follow the tone set by the host. Excessive complaining, showing off, or crude jokes were not allowed.

Praising the food, commenting politely on the entertainment, or engaging in light-hearted banter was encouraged.

Drunkenness was tolerated only when the host allowed it, often during the later stages of the comissatio or drinking session.

Guests who became too loud or disorderly risked being asked to leave or worse, ridiculed in front of others.

Good manners at the table were seen as a sign of self-control and breeding. The mocking work of Petronius, Satyricon, shows how breaches of etiquette at a dinner party could become a source of funny embarrassment, especially in scenes involving the fictional host Trimalchio.

What range of foods should you expect to be served?

A typical Roman feast progressed in several stages. The gustatio included light dishes such as eggs, olives, lettuce, radishes, and sometimes stuffed dormice or shellfish.

These were followed by the prima mensa, or main course, which might include roasted meats such as pork, duck, or boar, stews made from lamb or fish, and seasonal vegetables flavoured with garum, an anchovy-based sauce valued across the empire.

Ingredients such as pepper, cumin, and silphium were added for taste and health, though silphium had become very rare by the early Empire and may have already been extinct.

On special occasions, unusual foods such as sea urchins, sow’s udders or even flamingo tongues might appear.

Such rare foods appeared in high-end culinary texts, though they were not common in most households.

Many of these dishes are recorded in the surviving Roman cookbook De Re Coquinaria, attributed to Apicius.

The secunda mensa, or dessert course, often included fresh or dried fruits, nuts, honey cakes, and sometimes exotic treats imported from the east.

Wine was served throughout, usually watered down in accordance with Roman custom, a tradition inherited from Greek practices.

Strong drink unmixed with water was seen as uncivilised behaviour or poor self-control.

Each course was brought with formality, often on silver or bronze trays by slaves.

The visual presentation of the food mattered as much as the taste, and a colourful and textural presentation accompanied by appealing scents delighted the senses.

Terra sigillata pottery, or red-gloss tableware, often gave an extra visual effect to the meal, though such items were widely produced and not limited to the very wealthy.

When to bring a gift, and who to give it to

A gift was not strictly required for all feasts. It could help build favour or acknowledge a close relationship with the host.

Acceptable gifts included small items such as scented oils, wines, garlands, or baskets of fruit.

These tokens were usually handed to a household slave upon arrival or placed on a designated table.

Offering them directly to the host could be seen as drawing attention to oneself, unless the gift held particular significance.

Custom or imported items were especially liked, because they showed care and money.

In some cases, guests brought gifts to other guests of high rank instead of the host, especially when they wanted political support or patronage.

The Roman dinner party offered a stage for quiet dealings. Failing to bring a gift when others had done so could suggest a lack of thanks or poor manners.

However, offering something too extravagant might cause embarrassment or seem not genuine.

Roman dining customs required a careful balance between humility and honour, display and restraint.

Understanding how and when to offer a gift formed part of the wider ritual of Roman social custom.

Public officials might even include such events among their munera, or public duties.

Not being formal tax deductions in the modern sense, the expenses of such hospitality could boost a public figure’s reputation and political position.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.