Gateway to power: Understanding the benefits of Roman citizenship

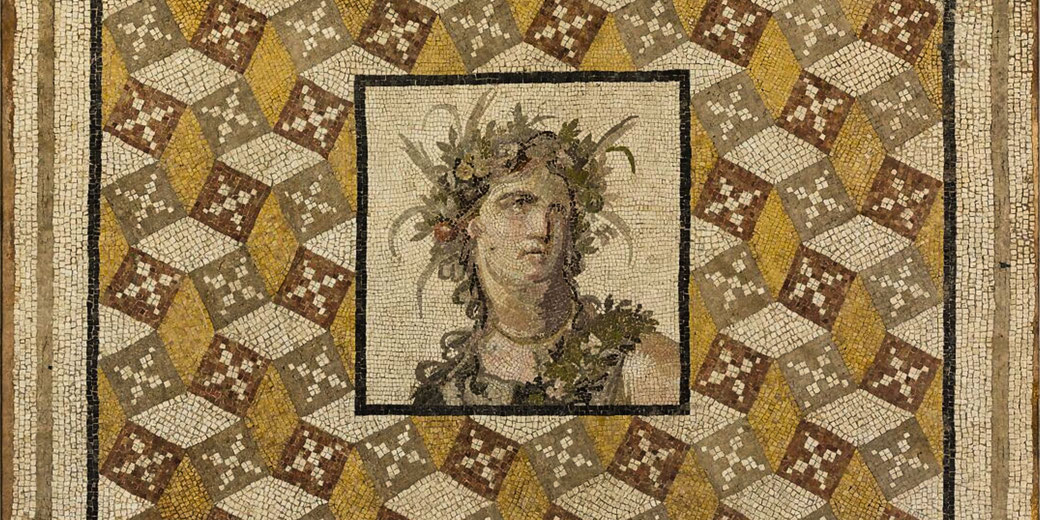

The Roman Empire relied on systems of inclusion and control, among which the most powerful incentives was the status of citizenship, which conferred rights and responsibilities that raised individuals and communities.

When historians have examined these benefits, they have discovered how Rome maintained loyalty and stable administration that improved efficiency across its territories.

How could someone become a Roman citizen?

Roman citizenship was given at birth when both parents were also citizens. In such cases, the child received full rights and joined a long-standing tradition that tied legal identity to family lineage.

If only the father held citizenship, the child could acquire full rights under Roman law, provided the parents had a legally recognised marriage under Roman conubium.

Among Roman families, this inheritance supported social order and preserved civic identity.

As the Republic grew, the extension of birthright citizenship ensured that loyalty to Rome continued across generations.

Importantly, manumission granted citizenship to former slaves. At formal ceremonies, freedmen received legal status that allowed them to vote and marry under Roman law.

Although some restrictions remained, their children held full citizenship without limitation.

Some freedmen, such as Tiberius Claudius Narcissus, a former slave of Emperor Claudius, rose to positions of significant influence in the imperial household.

In addition, service in the Roman military created a common path toward citizenship.

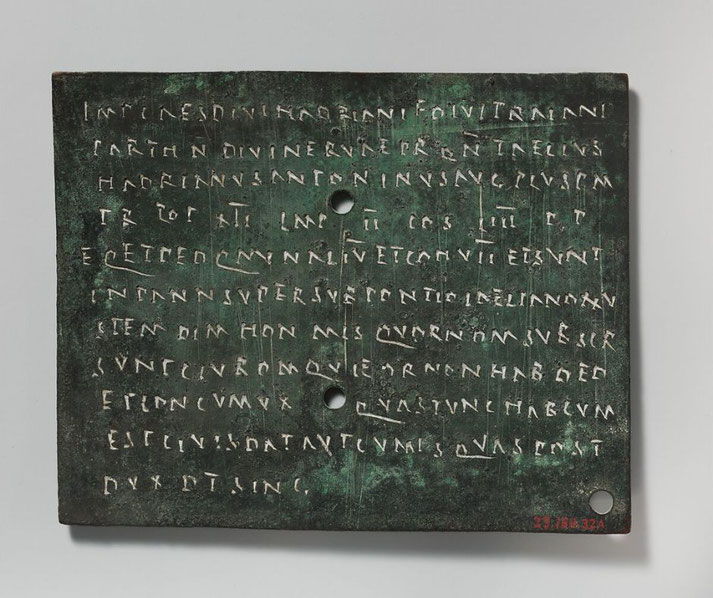

Auxiliary soldiers, once discharged, received formal documents known as diplomata, bronze tablets inscribed with the veteran's name, unit, and the emperor's seal, which confirmed their new status and extended the same rights to their families.

During the imperial period, hundreds of thousands of soldiers received citizenship in this way after twenty-five years of service.

At times, Roman leaders granted citizenship to entire communities. In recognition of loyalty or strategic importance, towns received decrees that brought their residents into the civic body.

These grants strengthened imperial control and tied local elites more closely to Rome.

The rights Roman citizens enjoyed

Roman citizens held the right to vote in public assemblies, elect magistrates, and approve laws.

Although power in these bodies favoured the wealthy, the right to vote gave each citizen formal participation in public affairs.

Citizens voted within centuries and tribes, each forming the basis of separate assemblies, the comitia centuriata and comitia tributa, which were structured in ways that gave more influence to property-owning classes, particularly in the centuriate assembly.

Furthermore, citizens could pursue public office. A man who entered the cursus honorum advanced through a sequence of magistracies with each step offering influence and access to higher social standing.

Citizenship brought legal protection, since citizens held the right of provocatio, which allowed them to appeal punishments or decisions made by magistrates.

They could not be tortured, scourged, or crucified, as these punishments were generally forbidden for Roman citizens under standard legal protections.

One well-known case involved Paul of Tarsus, who avoided illegal punishment in Judaea after asserting his citizenship.

His appeal forced local officials to change their course of action and send him to Rome for judgment.

Citizens also enjoyed private legal rights. They could own land, write wills, enter contracts, and marry under Roman law.

In legal terms, conubium gave them the ability to form recognised families whose children would inherit full civic status.

In some cases, citizens also received exemptions from certain taxes, such as the tributum capitis, which applied to non-citizens.

Different types of Roman citizenship

Roman citizenship did not exist in a single form. Full citizenship, known as civitas optimo iure, granted the right to vote, hold office, receive legal protection, and marry lawfully.

This status applied to citizens living in Rome and in officially recognised colonies.

In contrast, the Latin Right offered partial benefits. Towns with this status could conduct legal business, and their magistrates might gain full Roman citizenship.

Although they could not vote in Roman elections, they shared many of the practical advantages of citizenship.

Latin colonies often served as steps toward full integration.

In some cases, individuals held civitas sine suffragio, which included protection under Roman law but excluded voting and the right to hold public office.

This form of citizenship helped Rome control newly conquered territories without immediately granting political power.

Freedmen received a unique form of citizenship. After manumission, they could vote and participate in civil life, yet they remained barred from holding high office or joining the Senate.

Nevertheless, their children became full citizens and could pursue advancement.

How did citizenship expand as Rome grew?

At first, citizenship remained limited to Rome and nearby territories. During the conquest of Italy, Roman authorities extended limited forms of citizenship to allies, which created a system of legal inclusion without full political equality.

The Lex Julia de civitate Latinis et sociis danda of 90 BCE offered citizenship to allies who remained loyal during the Social War, and it was soon followed by the Lex Plautia Papiria of 89 BCE, which extended the offer more broadly to Italian communities that laid down arms.

During the Social War (91–88 BCE), Italian allies rebelled to demand full rights. In response, Rome granted citizenship to all free inhabitants of Italy who accepted Roman control, thereby ending the legal distinction between Romans and Italians.

Later, Julius Caesar used citizenship as a political reward. He granted the status to individuals and towns that supported him during civil conflict.

Augustus continued this practice and used it more widely across the provinces, especially to military veterans and loyal elites.

Military settlements played a major role in this process, as discharged soldiers received land, legal protection, and full citizenship.

These new communities, such as Emerita Augusta in Hispania, helped spread Roman institutions into frontier regions and stabilised recently conquered areas.

Eventually, in 212 CE, Emperor Caracalla issued the Constitutio Antoniniana, which granted citizenship to nearly all free men in the empire, though the exact scope remains debated among historians.

His decision removed the last major legal distinction between Romans and provincials.

Some historians suggest that Caracalla acted in part to increase the number of people eligible for taxation under Roman law.

As a result, Roman citizenship lost its special status but gained new importance.

Legal uniformity across the empire created consistent administration and increased the pool of those subject to Roman taxation and law.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.