The Res Gestae: Emperor Augustus’ most shameless form of self-promotion

Augustus understood that power meant nothing if it could not be remembered. After he had turned decades of instability into an empire under his control, he wrote his own version of history.

The Res Gestae Divi Augusti largely ensured that many Romans and later generations who encountered it would remember his reign as he wanted.

What is the Res Gestae Divi Augusti?

Augustus had prepared the Res Gestae Divi Augusti during the final years of his life because he knew that death would not stop him from speaking to the Roman world.

Its title, which translated as The Deeds of the Divine Augustus, already confirmed his plan to be declared a god, even though the Senate had not yet issued the formal decree.

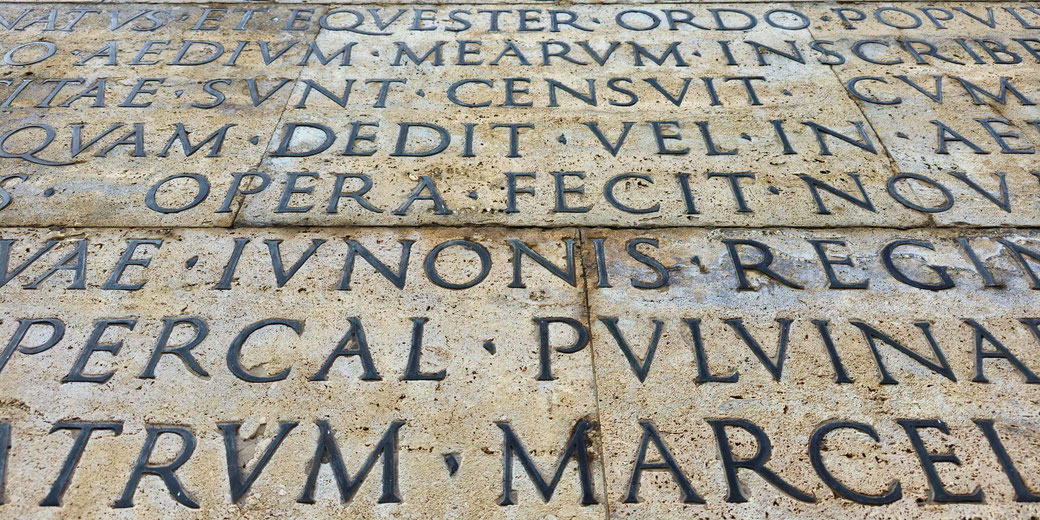

Although no archaeological evidence has confirmed the bronze tablets described in the Res Gestae itself, the most complete surviving version is carved into the walls of the Temple of Augustus and Roma in Ankara.

Within thirty-five carefully organised paragraphs, he separated his story into sections that generally addressed military victories, political power, public generosity, religious restoration, and his claim to have brought peace to the empire.

To emphasise his achievements, Augustus largely avoided a chronological narrative and instead listed his deeds by category.

Each section highlighted an area of Roman life where he claimed authority. He notably included statements about raising armies at his own expense, claimed he had rejected unconstitutional positions, and insisted that the Senate had offered him repeated honours.

According to the account, he claimed to have protected the res publica and to have respected traditional Roman customs.

However, these claims largely ignored the unlawful acts and political violence that he used to achieve complete control over the state.

Before he died in AD 14, Augustus had ordered that the text be engraved on bronze tablets and placed outside his Mausoleum in the Campus Martius.

By doing so, he largely guaranteed that many Roman citizens would encounter his narrative in a prominent public space.

Since the mausoleum became a place of public memory and worship of the emperor, the inscription allowed his voice to be part of daily Roman life for many people long after his death.

What Augustus wanted future generations to remember

The Res Gestae primarily attempted to explain his rule as the necessary result of Rome’s collapse into civil war.

At the beginning of the text, he claimed to have restored the republic by defeating those who threatened it, and he identified Antony directly while referring indirectly to the killers of Caesar without naming Brutus or Cassius.

Although he had avoided discussing Caesar’s assassination directly, he emphasised his duty to avenge his adoptive father.

As a result, he presented himself as the legitimate heir defending Roman values, rather than a politician exploiting public chaos for personal gain.

To construct an image of modesty, Augustus repeatedly described himself as a man who exercised restraint.

He used the phrase senatus consulto, which ostensibly suggested that the Senate approved his actions, even though he filled it with loyal supporters and controlled its agenda.

He also claimed to have refused the dictatorship and eventually gave up the consulship, which implied that he avoided absolute power.

However, after 23 BCE, he held tribunician power for life, which gave him authority over legislation and the right to convene the Senate.

His use of titles such as princeps and imperator allowed him to rule without interruption.

Therefore, by framing his decisions in terms of duty rather than self-interest, he helped to conceal the true extent of his control.

To strengthen his reputation as a benefactor, Augustus listed acts of generosity in great detail.

He had stated the number of gladiatorial shows that he had funded, the gifts of money that he had distributed, and the temples that he had repaired or built, according to his account.

These actions were evidence that he restored stability and revived religious life, producing improved prosperity across the Roman world.

In total, he claimed to have distributed over 600 million sesterces from his personal wealth.

By placing emphasis on his rebuilding of Rome and his enforcement of moral laws, Augustus styled himself as a new Romulus.

For Romans familiar with the city’s myths, this comparison positioned him as both founder and saviour.

How and where was it displayed?

After he had arranged the original bronze tablets in Rome, Augustus sent official copies to provincial cities, where they were carved into stone and placed on public buildings.

As mentioned above, the most complete surviving version appears at the Temple of Augustus and Roma in Ankara, where the text was written in both Latin and Greek.

Because many inhabitants of the eastern provinces spoke Greek, this translation likely allowed his message to reach audiences across linguistic boundaries.

Fragments have also been recovered from Pisidian Antioch and Ancyra, which suggests that multiple regions received this official version.

As a result, the Res Gestae became a tool of imperial propaganda across the entire empire.

In several cities, the inscription appeared on temple walls connected to the imperial cult, which meant that citizens encountered Augustus' words as they worshipped him as a god or offered prayers for his family.

Public devotion to him became inseparable from loyalty to Rome. As a result, his words acquired religious importance, supporting political loyalty and ritual respect.

Because the Res Gestae was intended for a wide audience, Augustus wrote it in plain, direct language.

He used the first person throughout the document, which gave the impression that he addressed the reader directly.

Each paragraph mentioned a specific achievement or act of generosity and omitted any mention of failure or controversy.

Since the text was easy to read aloud and understand, it could be used during festivals, religious rituals, or civic events to reinforce his preferred narrative.

Can we trust Augustus’ own version of history?

Historians have treated the Res Gestae as a valuable but biased source that must be compared with other evidence.

Augustus omitted any reference to the proscriptions he carried out with the Second Triumvirate, even though thousands of Roman citizens were executed and their properties seized.

He also failed to mention the destruction caused by his naval war against Sextus Pompey or the devastating campaign against Antony and Cleopatra.

By avoiding these events, he constructed a version of history where peace and order came from his leadership and not from violence.

Ancient writers who lived after his reign described a different version of events.

Suetonius and Cassius Dio recorded that Augustus maintained control through bribery and coercion, and by manipulating laws to secure his advantage over the Senate and the people.

Although he claimed to have preserved the republic, he ensured that no important decision could proceed without his approval, and his refusal to accept certain titles distracted from the fact that he exercised authority over military commands, provincial governors, public finances, and legal courts.

Since the Res Gestae expressed what Augustus wanted future Romans to believe, it is largely useful as evidence of imperial values and political strategy.

He praised religious piety and presented military strength as a form of civic responsibility because these were the virtues he wanted associated with his name.

Later emperors even imitated this strategy by issuing similar inscriptions, which means the Res Gestae also helped to influence the traditions of Roman imperial ideology.

As historian Ronald Syme observed, the Res Gestae should be seen as a monument to self-justification and a very selective account.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.