Ramses II's family feud: How the pharaoh's many children doomed Ancient Egypt's 19th dynasty

Great empires often fall through the slow erosion of unity within the realm rather than at the hands of enemies. The 19th Dynasty of ancient Egypt reached remarkable heights under Ramses II, whose campaigns and constructions declared a kingdom at its height.

Behind the glory, however, lay a dangerous imbalance: too many heirs, too little clarity. As Ramses aged and outlived generations of potential successors, his vast family turned from an asset into a problem.

The political fallout from his succession would prove more damaging than any foreign foe, which set in motion the dynasty’s decline.

The glorious rule of Egypt's most famous pharaoh

During a reign that lasted an unusual sixty-six years, Ramses II led what many later Egyptians viewed as a golden age in which steady rule bolstered the army and inspired ambitious building works.

When he ascended to the throne in 1279 BCE, Ramses II inherited a kingdom that had already been renewed by his grandfather Ramses I and his father Seti I.

He built on their successes by launching military campaigns into Canaan and Syria, most famously in which he fought the Hittites at the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BCE.

Although the battle ended in a stalemate, Ramses presented it as a great victory through temple reliefs and public inscriptions, ensuring his reputation as a warrior pharaoh.

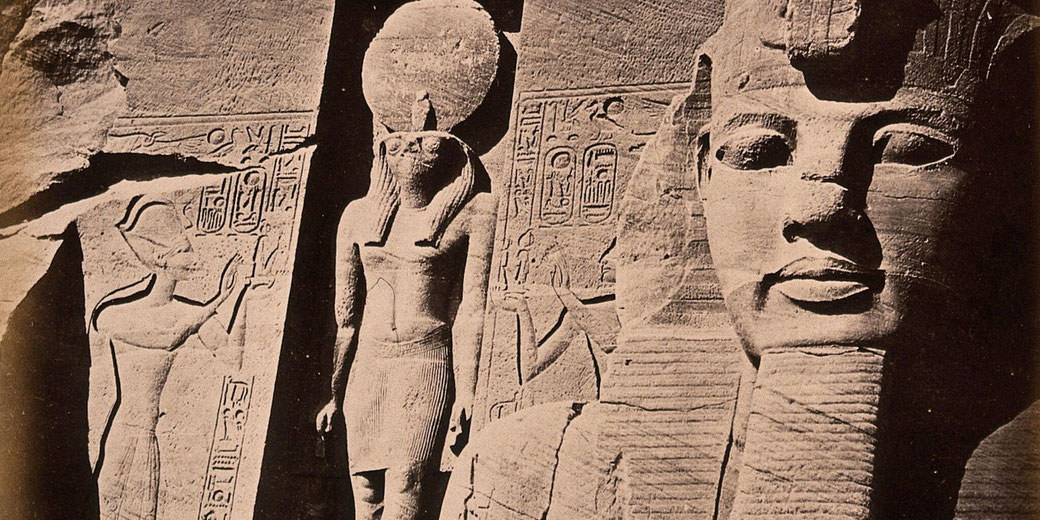

Alongside his military exploits, he changed the land with monuments, temples, and statues that proclaimed his greatness.

At Abu Simbel, Luxor, and Pi-Ramesses, his presence influenced the architecture of his era.

His construction of the Ramesseum, a mortuary temple dedicated to himself, reflected his desire to be remembered as a living god.

By the time of his death, around 1213 BCE, he had outlived many of his wives, courtiers, and military commanders.

However, his long rule and unusually large number of children laid the foundations for a bitter power struggle that would destabilise his successors.

The growing problem of a vast royal family

Through official wives, lesser consorts, and royal concubines, Ramses II fathered over one hundred children.

His chief queen, Nefertari, held considerable influence and bore several sons and daughters.

Another royal wife, Isetnofret, also produced multiple heirs, including the prince who would eventually succeed Ramses.

In the early years of his reign, Ramses took great care to promote his sons to important positions within the military, administration, and priesthood.

Scenes in temples across Egypt depict these princes who presented offerings beside their father, a visual cue to their rising authority.

As the decades passed, however, the number of eligible heirs multiplied. Ramses outlived at least twelve of his crown princes.

By the end of his reign, several surviving sons were already in advanced age themselves. This created an unstable situation.

The clear line of succession became unclear, and conflicts among half-brothers began to take root.

The royal court became a breeding ground for division, as influential families and priesthoods attached themselves to one potential heir or another, who sought to gain favour in a post-Ramses world.

What began as a symbol of royal strength eventually turned into a source of instability.

The struggle for succession

After Ramses II died, his thirteenth son, Merneptah, took the throne. By that time, he was already an elderly man, likely in his sixties.

His reign was short, lasting about a decade, and it faced early difficulties. Libyan tribes invaded the western delta, while grain shortages caused unrest throughout the Nile Valley.

Merneptah managed to suppress these threats, but his death sparked new tensions within the royal family.

A conflict broke out between his successor, Seti II, and a rival who claimed the throne named Amenmesse.

Historians remain divided on Amenmesse’s true identity, but it is clear that he held power in Upper Egypt for several years, which undermined Seti’s authority.

This fight for the throne reflected the deeper problems left behind by Ramses II’s large and divided family.

The children and grandchildren of Ramses, raised with special advantages and placed in strong positions, began competing for influence.

With no clear heir without dispute, the throne became a prize to be seized.

Government and temple leaders, once tightly controlled by a dominant pharaoh, now acted independently.

Egypt’s central authority began to break apart. As competing branches of the royal family backed different successors, each generation became more entangled in bitter disputes that sapped the state’s cohesion.

The decline and fall of the 19th dynasty

By the time of the pharaoh Siptah, who ruled from around 1197 to 1191 BCE, Egypt had entered a period of internal weakening.

Siptah was a young and possibly sickly ruler whose reign was largely controlled by his stepmother and guardian ruler, Queen Twosret.

After Siptah’s death, Twosret ruled in her own right, but her claim to the throne lacked broad support.

Her rule ended in civil conflict, likely involving a man named Setnakhte, who emerged as the founder of the 20th dynasty.

This forceful change confirmed the complete breakdown of the 19th dynasty’s authority.

The years following Ramses II’s death revealed the long-term dangers of uncontrolled growth of the royal family.

The competition among his many descendants, combined with Egypt’s financial problems and foreign threats, contributed to the kingdom’s weakening.

Without a clear and stable succession, Egypt slid into political breakup. The 19th dynasty, once so closely associated with strength and splendour, fell under the weight of internal rivalries and unresolved ambitions.

The family that Ramses II had proudly built up eventually tore itself apart, which brought an end to the era he had once ruled with his own confidence.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.