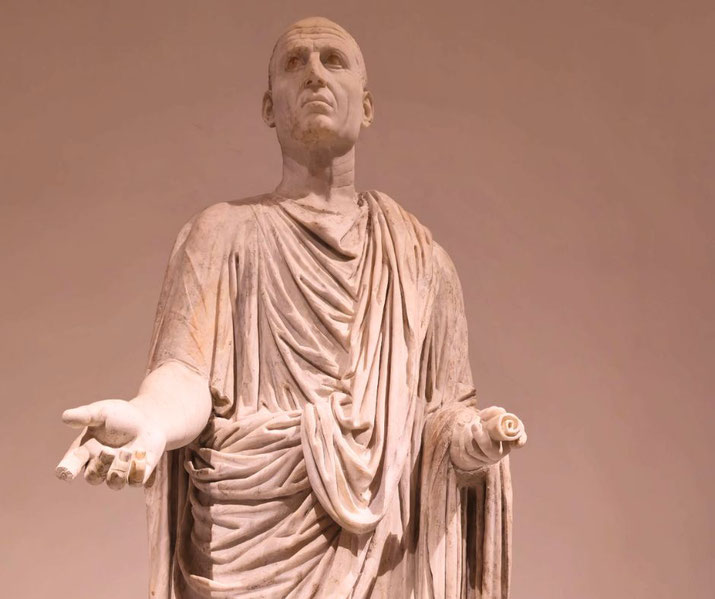

Quintus Fabius Maximus: the man who saved Rome from Hannibal, but was then ignored

During one of its darkest hours, Rome faced an opponent whose brilliance on the battlefield seemed unstoppable. Amid the calls for glory and vengeance, one leader stepped forward with a strategy that relied on erosion rather than confrontation.

Though his policy preserved the state, the same people who were saved soon looked away, and they chose pride over prudence.

Hannibal's Invasion and the Roman Crisis

Hannibal Barca, son of Hamilcar and veteran of the First Punic War, launched his campaign against Rome after he crossed the Alps in late 218 BCE.

He brought with him a multi-ethnic army of Libyans, Spaniards, Celts, and elephants.

After he survived the dangerous journey through the mountains, he won swift victories against Roman forces at the Battle of the Ticinus River and then at the Trebia.

The following year, in 217 BCE, he ambushed and destroyed another Roman army at Lake Trasimene.

Ancient sources record that this action killed an estimated 15,000 soldiers and captured thousands more.

Rome was shaken to its core. Hannibal had pierced into the Italian heartland and proved unbeatable in direct battle.

In response, the Senate appointed Quintus Fabius Maximus as dictator rei gerundae causa and granted him special powers to steer the Republic through its greatest crisis.

Fabius had already served as consul twice, first in 233 BCE, when he celebrated a triumph for defeating the Ligurians, and again in 228 BCE.

He was also an augur and the princeps senatus, positions that added moral and political authority to his decisions.

Respected for his discipline and religious devotion, he would now take a radically different approach from his predecessors.

The Fabian Strategy: Delay, Disrupt, Deny

Fabius refused to offer battle. Instead, he adopted a scorched-earth policy. He destroyed crops and villages in Hannibal's path, denied him food supplies, and used the Roman legions to shadow the Carthaginian army without committing to combat.

Fabius hoped to weaken Hannibal's resources and spirit when he stretched out the campaign indefinitely.

He placed Roman troops on high ground and along the Apennine ridges, forced Hannibal into less fertile regions such as Samnium, and prevented any direct access to Rome or its most loyal allies in central Italy.

Ultimately, this strategy came to define him, and his method became known as Fabian tactics: a term still referenced in historical and strategic studies.

However, to many Romans, this seemed more like cowardice than strategy. His avoidance of battle clashed with the Roman martial tradition.

However, the most critical episode of this phase of the war unfolded in Campania, where Fabius’s cautious approach met Hannibal personally.

Hannibal’s Ager Falernus Escape

In January 217 BCE, during his time in office as dictator, Livy (XXII.8-12) records that Fabius commanded an army of roughly 20,000 infantry and sent cavalry units to secure the passes near Casilinum in the Ager Falernus region of Campania.

He pursued Hannibal with a strategy that aimed to wear down the enemy rather than bring about an open battle.

He blocked the narrow pass that ravines flanked above the River Volturnus because he believed that a lack of supplies would force the Carthaginian army’s hand.

However, when Hannibal had approximately 20,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry, he responded with a clever night-time trick.

He seized around a thousand local oxen and tied bundles of lighted sticks to their horns.

As darkness fell, his men drove the flaming animals along the slopes overlooking the plain.

That action startled the Roman sentries and led them to believe that an enemy breakout or ambush was underway, as Polybius (III.28) records.

Marcus Minucius Rufus held the position of Fabius' Magister Equitum and he made rash movements that nearly split the Roman command.

He led part of the legions toward the ridge and left the narrow pass unguarded.

Meanwhile, Hannibal guided his entire force, including infantry, cavalry, and baggage trains, through the now open valley into safety.

By dawn the Carthaginian army was out of reach and no engagement had occurred.

Many Roman politicians dismissed the event as a failure of Fabius’s leadership rather than proof of Hannibal’s skill.

Later traditions said that Fabius’s caution showed a lack of boldness. In response to public frustration, the Senate granted Minucius equal imperium for sixteen days.

That decision weakened the effectiveness of the original Fabian approach.

Political Rejection and the Disaster at Cannae

Fabius' dictatorship only lasted six months because Roman law set that limit.

When he stepped down in 216 BCE, Roman voters turned away from his approach and placed their hopes in the consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro.

These commanders raised the largest army Rome had ever fielded, over 80,000 men, and marched to confront Hannibal directly near the town of Cannae.

Fabius warned against this decision, but his advice was ignored.

The result was one of the most severe defeats in Roman history. Hannibal lured the Romans into a trap and then surrounded them with his flexible infantry lines and stronger cavalry.

He then killed nearly the entire army. Between 50,000 and 70,000 Romans died in a single day.

More than 80 senators were among the dead. That number made up a significant portion of the Senate, likely close to a quarter of their total.

As a consequence, Roman morale collapsed. Many Italian allies defected, including Capua, Tarentum, Lucania, Bruttium, and parts of Samnium.

The Senate, once hostile to Fabian tactics, now saw the wisdom in delay and attrition.

Rome brought back his approach, though Fabius himself would never again hold unchecked command over the war effort.

Return to Influence and the Slow Path to Victory

After Cannae, Fabius held the consulship in both 215 and 214 BCE. He focused on regaining Roman control over territories that were in rebellion, and he worked to restrict Hannibal's movements in southern Italy.

In 212 BCE, he successfully recaptured Tarentum through a combination of careful planning and the arranged betrayal of a Tarentine officer.

The officer agreed to betray the city and Roman soldiers were able to scale the walls by night and open the gates.

Although Fabius never again led Rome's principal field army against Hannibal, his influence helped Rome to recover from its early defeats and regain strategic initiative.

Fabius argued constantly for a war of attrition. He opposed any peace negotiations with Hannibal and warned against sending forces too far away.

When Scipio Africanus proposed an invasion of North Africa in 205 BCE, Fabius objected strongly, fearing that Hannibal would return to Italy and that Rome lacked the strength to sustain an overseas campaign.

The Senate approved the invasion anyway. Scipio's plan led to the Roman victory at Zama in 202 BCE, and that result brought the Second Punic War to an end.

Though Fabius died in 203 BCE and did not live to see the victory, his plans had kept the Republic long enough for that final victory to occur.

Later writers praised him as the man "who by delaying restored the state to us."

History has rarely changed that judgment.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.