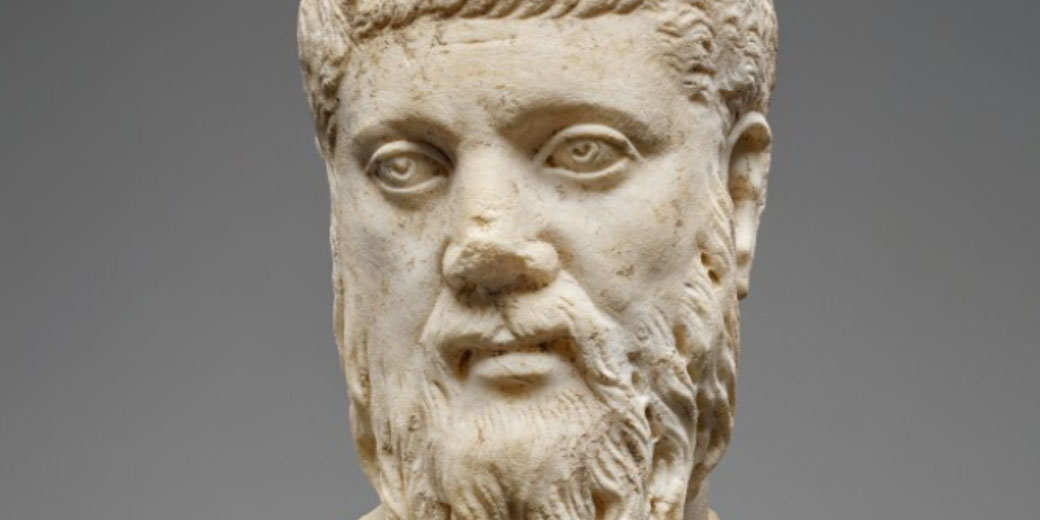

Why Plato was the greatest philosopher of the ancient world

Plato achieved a level of influence unmatched by any other philosopher of the ancient world. His writings introduced entirely new ways of thinking about reality, which challenged conventional approaches to knowledge and ethics.

As a result of the lasting power of his dialogues, he developed methods grounded in reasoning and idealism alongside principles of political theory that shaped classical philosophy and laid the intellectual foundation of the Western tradition.

The world that Plato grew up in

Plato was born in 428 or 427 BCE into a noble Athenian family during the final phase of the Peloponnesian War.

His father, Ariston, was traditionally said to descend from the early king Codrus, while his mother, Perictione, traced her family line to the lawgiver Solon.

That prolonged conflict between Athens and Sparta produced political instability and economic strain, which left citizens disappointed with democratic institutions.

After the Athenian defeat in 404 BCE, a brief and violent period of rule by a small group known as the Thirty Tyrants imposed harsh control before the restoration of democracy in 403 BCE.

One of the most brutal figures among the Thirty was Plato’s relative Critias.

In the public spaces of Athens, intellectual thought remained alive, though the city experienced political turmoil.

Dramatists such as Sophocles and Euripides posed moral questions on the stage.

Historians like Thucydides examined the causes and consequences of political failure, while pre-Socratic philosophers explored questions about the study of the universe and natural philosophy.

Plato himself received a traditional aristocratic education in music, grammar, athletics, and geometry, but philosophical questions soon captured his attention.

Eventually, Plato became disillusioned with the competing political ideologies of his time.

His relatives Charmides and Critias became leaders under the Thirty Tyrants, and their abuses of power discredited any trust in that form of government.

After democracy was restored, the execution of Socrates in 399 BCE convinced Plato that the city could be just as dangerous when guided by ignorance and emotion.

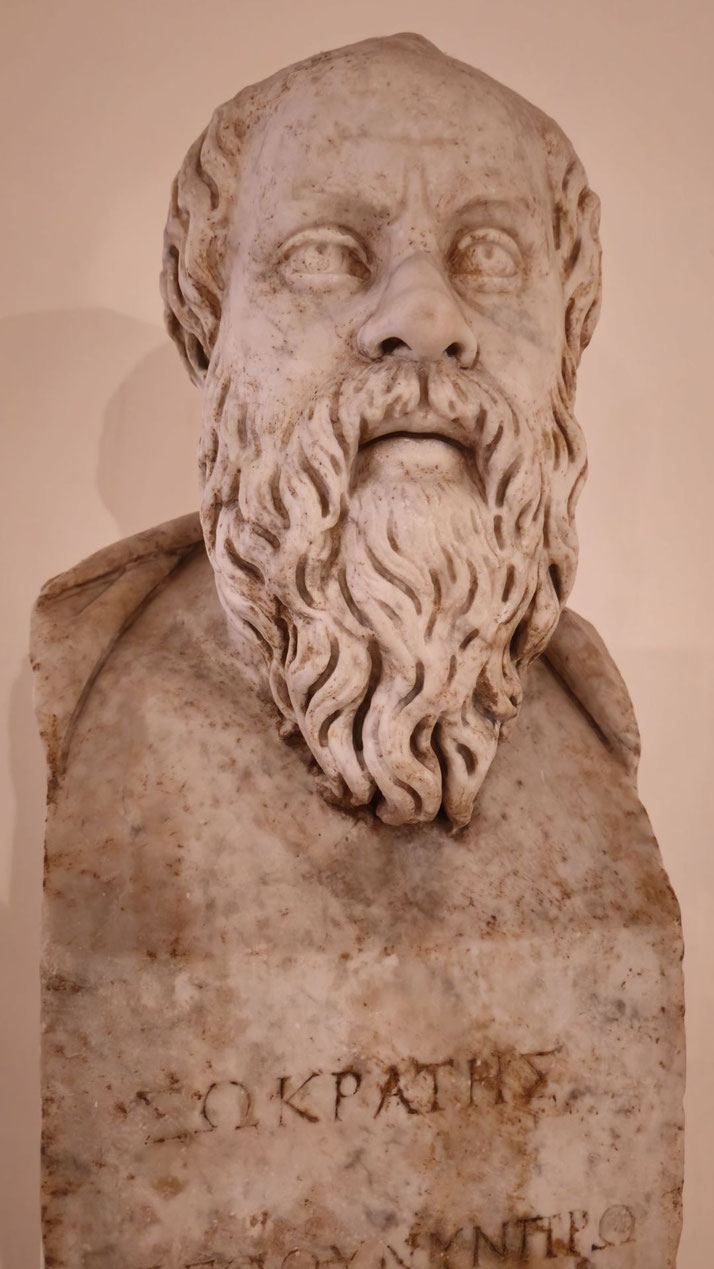

Socrates' profound influence on Plato

Plato encountered Socrates as a young man and quickly became his devoted student.

Socrates asked simple but straightforward questions that exposed contradictions in widely accepted ideas.

He engaged in public conversation rather than delivering lectures, and his reasoning cut through assumptions with clarity.

Without appealing to authority or writing anything down, he offered a living model of philosophy in action.

Significantly, the trial and execution of Socrates in 399 BCE altered the course of Plato’s life.

The charges of impiety and corruption masked deeper fears among Athenian citizens about the role of questioning in public life.

Socrates was sentenced to death by hemlock poisoning at the age of 70. Plato saw the death of Socrates as the unjust condemnation of a man who had devoted himself to truth rather than the punishment of a criminal.

In response, he committed himself to philosophy and he wrote dialogues that preserved Socrates’ voice.

Over time, Plato expanded those dialogues outside his teacher’s inquiries. He constructed more extensive philosophical arguments grounded in logic and the study of existence.

However, Socratic dialogue became a tool for exploring topics such as justice, virtue, love, and the soul.

The figure of Socrates remained central to Plato's writings as a representation of what it meant to live philosophically rather than a nostalgic tribute.

Some of Plato's most famous dialogues include the Republic, the Phaedo, the Symposium, the Meno, and the Timaeus.

Plato's most important philosophical ideas

At the core of Plato’s philosophy stood the theory of Forms. This doctrine proposed the existence of perfect, eternal realities outside the material world.

A physical object, such as a tree or a chair, could only ever be an imperfect reflection of its ideal Form.

The same concept applied to moral and abstract qualities such as beauty, justice, and goodness.

In one of his most famous analogies, Plato described prisoners in a cave who watched shadows cast on a wall.

The cave represented ignorance, and the shadows symbolised the misleading appearances of the physical world.

Only the philosopher, who turned away from the shadows and ascended into the sunlight, could perceive truth.

This image appears in Book VII of the Republic and expresses his concept of the Good as the highest Form, which illuminated all others.

In addition, Plato believed that the soul existed before birth and retained some memory of the Forms.

He argued that learning involved recalling knowledge rather than discovering it. In the Phaedrus, he used the image of a charioteer who guided two horses to describe the soul’s inner conflict, where reason had to manage both energetic and unreasonable impulses.

He also connected knowledge and virtue. He claimed that those who did wrong did so from ignorance.

True understanding would lead to fair behaviour, and a well-ordered soul would reflect the balance required for a just life.

In the Republic, he argued that fairness in the city matched fairness in the individual, with each part performing its proper role under the control of reason.

Plato founds his own school

In the early 380s BCE, Plato founded the Academy near the groves sacred to the hero Academus.

From its start, the school welcomed students who were interested in mathematical and philosophical inquiry through structured discussion.

Rather than use strict teaching methods, Plato promoted discussion and careful thought.

In its design and purpose, the Academy set an example for future centres of learning.

According to tradition, the phrase “Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here” was written at its entrance.

Among the subjects taught at the Academy, mathematics had special emphasis.

Geometry, in particular, helped students train their minds to work with abstract ideas.

In Plato’s view, the subject prepared the soul to understand the Forms. Astronomy and harmonics also featured in the lessons, as they showed order and regular patterns in the universe.

Over time, the Academy attracted curious thinkers from across the Greek world.

One of the most notable students, Aristotle, spent twenty years there before moving on.

Years later, around 335 BCE, he opened the Lyceum in Athens. Although Aristotle disagreed with many of Plato’s ideas, he kept the careful habits of investigation that his teacher had shown.

The Academy therefore set a lasting academic tradition. A later Platonic school in Athens, seen as continuing Plato’s work, remained active until it was closed by the emperor Justinian I in 529 CE.

At several points in his life, Plato tried to put his theories into practice. On journeys to Syracuse, he attempted to influence Dionysius the Elder and later his son, where he hoped to guide them toward rule by wise leaders.

These attempts failed, but they showed his belief that knowledge should guide action, and that only the learned should lead a fair state.

Plato's influence on later philosophers

After Plato’s death around 347 BCE, his ideas continued to shape every major area of philosophy.

His dialogues were kept, studied, and copied. Later thinkers adopted, changed, or challenged his views, but no philosophical movement could ignore them.

In the 3rd century CE, Plotinus revived and reinterpreted many of Plato’s ideas in the philosophy known as Neoplatonism.

With the help of his student Porphyry, Plotinus collected the Enneads, which described a system centered on the One as the source of all being.

This view brought Plato’s influence into the spiritual traditions of the Roman Empire and helped frame Christian theological debates for centuries.

Neoplatonism also spread into Islamic philosophy, bringing Plato’s thought to thinkers such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna.

For medieval scholars, Plato offered both clear structure and moral guidance.

Church Fathers such as Augustine used his ideas to explain the soul’s divine origin, the nature of evil, and the path to salvation.

From Augustine’s writings, Platonic concepts spread across medieval Europe to later Christian philosophers including Boethius, Anselm, and Thomas Aquinas who kept many Platonic ideas alive.

During the Renaissance, humanist scholars rediscovered Plato’s original texts and returned to his way of questioning.

Translations into Latin and common languages allowed wider access to his works.

Marsilio Ficino, who was supported by Cosimo de' Medici, translated all of Plato’s works into Latin and started a new Platonic Academy in Florence.

Thinkers such as Pico della Mirandola, who used Ficino’s interpretations, saw in Plato a guide to human worth, moral reasoning, and the unity of knowing and doing what is good.

Today, Plato’s dialogues remain essential to the study of philosophy. The questions he asked about abstract ideas and his vision of a fair society continue to stir discussion.

In academic, political, and ethical conversations, his heritage endures as an invitation to think carefully about what truth and fairness require instead of as fixed answers.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.