Why are the planets named after Roman gods?

When people in the ancient world observed the sky, they noticed five wandering lights that behaved differently from the stars.

These objects in the sky traced steady paths across the heavens and became connected with the divine. Over time, each one received the name of a Roman god, and that naming tradition formed the identity of the planets even into the modern era.

How the Romans thought about their gods

Romans believed that divine forces controlled the natural world, influenced human fortunes, and demanded regular acts of worship in return for protection and stability.

Rather than placing emphasis on the moral teachings or mythological adventures of the gods, Roman religion focused on correct rituals and maintaining a favourable balance between mortals and deities through offerings, sacrifices, and official ceremonies.

Because the concept of pax deorum, or "peace with the gods," showed their belief that the favour of divine beings determined the welfare of the Roman state,

Roman leaders responded to unusual events in the sky, such as comets or eclipses, by ordering extra sacrifices to restore divine favour.

For that reason, religious activity took place under the supervision of appointed priestly colleges such as the pontifices, augures, and haruspices, who read what the gods wanted from omens and events in the sky.

Because they did not simply observe the heavens to gain scientific knowledge, they performed astronomical calculations to plan festivals, prepare farming calendars, and decide what eclipses, comets, and planetary alignments meant.

As Roman religion absorbed ideas from neighbouring cultures, especially from the Greeks, the gods had developed clearer personalities and stories.

Though early Roman deities had been tied to concepts or functions without consistent human traits, later worship gave each god a defined mythology, appearance, and sphere of influence.

Greek myths had entered Roman culture because of conquest, trade, and literature, and Roman scholars had aligned their gods with those of Greece in a process known as interpretatio graeca.

Once Roman religion had become entwined with Greek-style storytelling, the planets gained names that showed the attributes of specific divine figures.

Although the Roman system of planetary naming aligned with mythological identities, this identification was not written down in scientific texts such as Ptolemy's Almagest, which used Greek names and focused on mathematical astronomy rather than mythology.

The Roman gods each planet was named after

Roman astronomers, who observed the five visible planets with the naked eye, had identified each one by its movement and appearance before assigning it to a deity.

The wandering nature of these bodies, which differed from the fixed stars, generally suggested divine motion and influence, and each planet became associated with a god whose power matched what people believed the planet's movement signified.

These five planets, which had been known since antiquity, had been recorded by Babylonian and Greek astronomers before receiving their Latin names.

For example, Mercury, which typically moved across the sky faster than any other planet, became connected with the swift and quick god who guided souls to the underworld, delivered messages, and influenced commerce.

His role as an messenger matched the planet's brief path near the sun, visible only for short periods before dawn or after dusk.

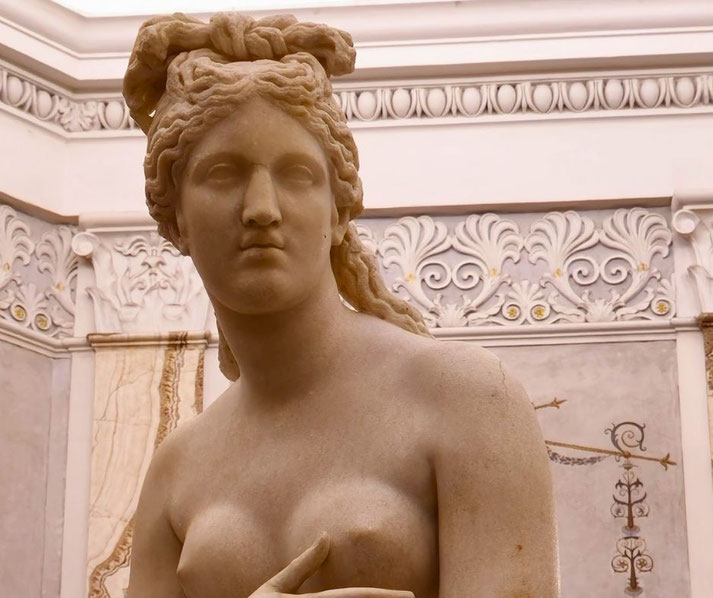

Venus, which was known for its brightness and position as the morning or evening star, earned its name through its association with the goddess of love and beauty, who also oversaw fertility.

Its striking appearance and soft light gave it a reputation for grace and attraction, which matched Roman descriptions of Venus as both a nurturer of life and a powerful divine influence over human desire.

Mars, which appeared as a reddish light in the sky, became connected with the Roman god of war.

The colour reminded observers of blood, battlefields, and aggression. Roman culture held Mars in high regard because of his warlike nature and because of his connection to Rome's founding myth, which claimed that Romulus and Remus were his sons.

The name for Tuesday, or dies Martis, preserved this association in Latin-speaking traditions, which had adopted a planetary week structure from earlier Hellenistic models influenced by Greek astrology.

Jupiter, which was brighter and larger than the other planets, received the name of the king of the gods. Romans associated him with thunder, law, justice, and political order.

His placement high in the sky and his slow, steady motion showed authority and permanence, and Roman religion gave him central importance in both public and state rituals.

Saturn, which was visible only at great distance and moved slowly, became connected with the ancient god of agriculture and time.

Saturn's mythological reign was remembered as a golden age of peace and prosperity, and the planet's faint glow suggested something old and remote, connected to the cycles of planting, harvesting, and renewal.

Since the Roman Saturn was primarily associated with agriculture and later interpretations influenced by the Greek Cronos contributed to his connection with time, the connection between Saturn and time also influenced the naming of Saturday, or dies Saturni.

Why were new-found planets also named after the gods?

When astronomers in the modern era began to discover new planets with telescopes, they retained the Roman tradition that had governed planetary naming since antiquity.

Uranus, which William Herschel discovered in 1781, required a name that would match the others already known.

Although Herschel initially proposed naming the planet Georgium Sidus after King George III, astronomers rejected naming it after a living ruler.

Johann Bode later suggested "Uranus," a name drawn from Greek mythology, which referred to the sky deity and father of Saturn.

Though the name came from Greek rather than Roman religion, it fit the mythological order and kept the system consistent, but it used a Greek name rather than a Roman one.

Neptune, which was discovered in 1846 due to its gravitational effects on Uranus, appeared blue when viewed through telescopes.

Because of its colour and oceanic meaning, astronomers named it after the Roman god of the sea.

The name Neptune matched both the visual appearance of the planet and the tradition of linking objects in the sky to powerful mythological forces.

Pluto, which Clyde Tombaugh discovered in 1930, orbited at the outer edge of the solar system and appeared small and cold, with a dark appearance, because its distance made it suitable for the name of the god of the underworld, who ruled the hidden realm of the dead.

Venetia Burney, who was a young English schoolgirl, proposed the name.

Astronomers approved it because it continued the mythological pattern and provided an appropriate connection between the planet's qualities and Roman religion.

Pluto's largest moon, which was Charon, received the name of the mythological ferryman who carried souls across the river Styx in Greek mythology, continuing the use of classical traditions even when they originated from outside the Roman pantheon.

Afterwards, astronomical discoveries continued to draw from mythology, even when categorising dwarf planets and moons.

Scientists, who had recognised the influence of tradition and the importance of meaning, preserved the classical naming system rather than replacing it with modern, scientific, or nationalistic names.

Moons of Uranus, however, departed from this pattern because they drew names primarily from characters in the works of Shakespeare, with a few also taken from Alexander Pope's writings.

Other dwarf planets such as Eris and Haumea took names from Greek and Hawaiian mythology, which showed a wider but still mythologically based practice.

The Roman pantheon gave scholars in Europe a common set of names and generally kept consistency with earlier periods of celestial study.

How have other cultures named the planets?

Long before the Romans, other civilisations had named the planets and assigned them to divine figures based on cultural and religious beliefs.

Babylonian astronomers recorded the planets on clay tablets and linked each one with a god from their own pantheon.

Venus became Ishtar, the goddess of love and war, Mars became Nergal, a god associated with plague and conflict, and Jupiter was associated with Marduk, the chief deity.

Their planetary records, preserved in cuneiform, influenced later Greek and Roman astronomy after centuries of transmission, although the associations between planets and deities varied across different periods of Babylonian history.

Elsewhere, in ancient China, astronomers used the Five Elements system to classify planets, linking each one to natural substances rather than divine beings.

Mercury became the Water Star, Venus the Metal Star, Mars the Fire Star, Jupiter the Wood Star, and Saturn the Earth Star.

In the Indian tradition, the planets belonged to the Navagraha, a group of nine celestial beings who influenced fate, health, and karma.

Each major planet was associated with a specific deity: Mars with Mangala, Venus with Shukra, Jupiter with Brihaspati, and Saturn with Shani.

Ancient Sanskrit texts recorded astronomical positions and rituals to mitigate the effects of unfavourable planetary alignments.

Arabic-speaking astronomers during the medieval period translated, preserved, and improved upon Greek and Roman astronomical texts.

They wrote in Arabic and preserved the astronomical knowledge of the Greeks, though they often used Arabic names for the planets, such as Al-Merrikh for Mars and Zuhal for Saturn.

The Latin names returned to prominence in Europe during the Renaissance, when classical texts were translated from Arabic into Latin.

Their works eventually passed into Europe during the Renaissance and helped revive interest in ancient astronomy.

As Latin translations spread through universities, the Roman naming system returned to prominence.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.