How the devastating Plague of Athens brought an ancient superpower to its knees

In 430 BCE, during the height of its power, the city of Athens faced an enemy it could neither escape nor defeat. A deadly outbreak erupted inside the city walls and the so-called Plague of Athens spread through its jammed streets.

Democratic institutions collapsed under the weight of mass suffering, and the death toll stripped Athens of its leaders and the military cohesion needed to maintain resolve.

Why Athens was distracted by war at the time

Athens had committed to a long-term defensive strategy during the Peloponnesian War, as devised by Pericles, who relied on the strength of the navy and the safety of the city’s Long Walls.

To protect its citizens from Spartan invasions, rural populations were ordered to abandon their farms and relocate inside the protected urban area.

That decision, while practical from a military perspective, pushed the city’s population far beyond its intended limits.

Estimates suggest that the total population of Athens, including slaves and foreign residents, may have reached up to 250,000.

In the strained districts of the city, conditions deteriorated rapidly. Refugees crammed into temples, porticoes, and private homes, which placed major pressure on supplies and cleanliness and undermined civic order.

Food deliveries from the empire became essential for survival, and overcrowding led to widespread malnutrition that aggravated disease and sparked unrest.

The government, prioritising military operations and naval expeditions, failed to respond to the mounting domestic crisis.

At the same time, displaced citizens grew resentful over the destruction of their farmlands.

What is more, urban households, already strained, struggled to accommodate the new arrivals.

Each Spartan invasion stirred panic and resentment, yet public attention remained fixed on the war’s outcome.

Pericles’ strategy continued to avoid direct confrontation on land, but the packed conditions of the city created a new and far deadlier danger.

The sudden outbreak of disease

Eventually, the disease entered Athens at Piraeus, the city’s crowded port, where it struck sailors, traders, and labourers.

As the main hub for imported food and goods, Piraeus offered the most vulnerable entry point.

It spread rapidly into the city’s interior and, in a matter of days, neighbourhoods became unfamiliar as death overtook the most crowded quarters.

Soon after the first signs, panic took hold of the medical community. Those who attempted to treat the ill died quickly, and no clear remedies existed.

With medical knowledge limited to humoral theory and traditional remedies, many patients received care that worsened their condition.

Some turned to ritual, while others withdrew entirely. Thucydides, who caught the disease and survived, recorded that no prior medical experience had prepared physicians for what they faced.

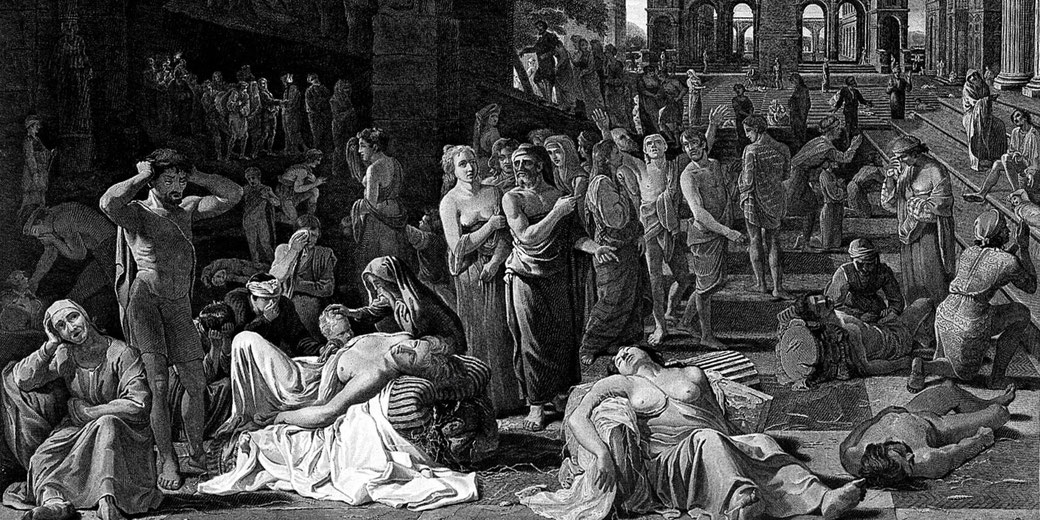

As the crisis deepened, bodies remained unburied and public spaces filled with corpses.

Officials lost control, priests abandoned their posts, and even basic functions of the state stopped.

Entire districts became silent, their residents either dead or dying.

The gruesome symptoms of the plague

According to Thucydides, the illness began in the head. Patients experienced eyes that burned, throats that swelled, and fever.

As the disease progressed, symptoms included violent coughing, vomiting, intense thirst, and open sores.

In some cases, the plague destroyed extremities or caused complete confusion.

Thucydides wrote that "no one was willing to persevere in doing what was right," and that despair overwhelmed every moral boundary.

Often, patients screamed uncontrollably or begged for cold water. Some lost their minds before they died.

Those who survived carried lifelong injuries or disabilities. Even short-term recovery did not guarantee lasting health.

Understandably, families struggled to care for their relatives, and even neighbours avoided contact.

In many homes, the sick died alone.

Fear and hysteria take hold of the city

Before long, the entire city abandoned its usual order. For example, funeral rites, once sacred, vanished altogether.

Instead, citizens tossed the dead into fires prepared for others because graveyards overflowed with bodies.

Athenians believed that burial ensured passage into the afterlife, and its loss intensified spiritual pain.

Soon, people stopped following the law. Religious sanctuaries emptied. Temples no longer offered comfort.

Priests died in their robes, and citizens lost faith in divine justice. Some Athenians believed that the gods had turned away from the city.

Every corner of the city became haunted by silence, fire, or wailing.

Eventually, citizens gave in to selfish behaviour: some drank to numb the fear, while others stole what they needed or desired.

Since both good and wicked people died at the same rate, many believed no moral order remained.

Thucydides remarked that people no longer expected to live long enough to face judgement.

Pericles' vital leadership would cost him his life

Initially, Pericles remained calm. He addressed the Assembly, encouraged the people, and urged discipline.

His voice provided direction, even as his family suffered. Two of his sons, Paralus and Xanthippus, died during the outbreak, which added to his personal grief and diminished his remaining family.

The burden on him grew heavier with each passing month.

Eventually, Pericles fell ill. Though he recovered once, his health declined again. In 429 BCE, he died.

His death shook the city more than any single military loss. With him died the strategic planning that had guided Athens through war and prosperity.

Following his death, the Assembly descended into factionalism. Charismatic figures stirred public emotions and pushed for aggressive campaigns.

One prominent figure who rose in influence after Pericles’ death was Cleon, who promoted more confrontational policies.

Without Pericles’ moderation, Athens made a series of poor decisions. Among these was the Sicilian Expedition of 415 BCE, which ended in total disaster by 413 BCE.

What was the true nature of the disease?

Since ancient times, researchers have debated the plague’s identity. Thucydides’ detailed description has formed the basis of modern study.

Typhoid fever remains a main theory. However, other possibilities, such as smallpox, measles, or viral haemorrhagic fever, have also been proposed.

In 2006, archaeologists examined remains from a mass grave in the Kerameikos district, which revealed a hurried and disordered burial, with bodies stacked without care or ceremony.

DNA tests conducted by a team led by Manolis Papagrigorakis revealed traces of Salmonella enterica, a bacterium associated with typhoid.

However, some scholars have questioned the results due to the limited sample size and potential for taint.

This evidence supported the typhoid theory, but several of Thucydides’ symptoms remain inconsistent with that disease.

Some researchers think that multiple infections may have struck simultaneously.

Harsh hunger and crowded conditions under strain could have worsened the effects.

In the absence of further remains to study, the exact cause remains unknown.

How and when did the Plague of Athens end?

The plague lasted several years. The worst wave hit between 430 and 426 BCE, with smaller outbreaks in 425 and 423 BCE.

The disease eventually disappeared, although no clear reason explained its retreat.

Thucydides noted that it faded after it had devastated the population and reappeared sometimes in later years.

Some suggested that people built some resistance. Still others suggested that the pathogen mutated into a less lethal form.

Following the final wave, the scale of the destruction became clear. Estimates suggest that one-quarter to one-third of the population died, possibly 75,000 to 100,000 people.

Among the dead were soldiers, priests, politicians, farmers, artisans, and scholars.

Families lost entire generations, which meant that the army shrank, and the economy slowed.

Neighbouring states avoided contact with Athens, and some even took advantage of its weakened position.

In the years that followed, Athens never fully recovered. Confidence in democracy declined as political extremism increased.

Although the Peloponnesian War continued, the city that fought it had changed completely.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.