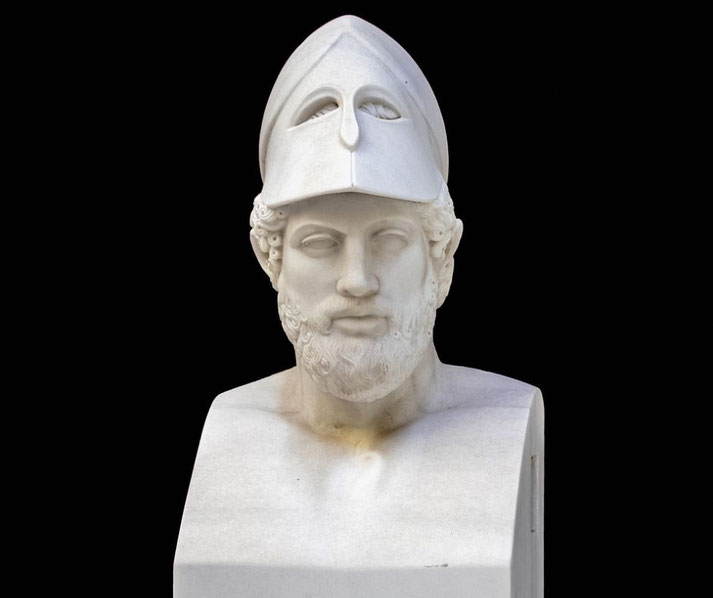

Pericles' visionary leadership of ancient Athens at the height of its power

Pericles became one of the most influential figures in Athenian history during the city’s golden age in the fifth century BCE, and he guided Athens through decades marked by stable rule while nurturing its cultural vitality and reinforcing its military capabilities.

His political control began to develop after the assassination of Ephialtes around 461 BCE, and from that time until his death in 429 BCE, Athens expanded its empire, strengthened its democratic institutions, and witnessed a flourishing of artistic achievements.

Pericles' early life

Pericles was born in 495 BCE into a wealthy and politically connected family in Athens, and he inherited both privilege and the expectation of public service.

His father Xanthippus had commanded Athenian forces at the Battle of Mycale in 479 BCE during the Persian Wars, and his mother Agariste came from the powerful Alcmaeonid clan that had long influenced Athenian politics.

The family’s influence ensured that Pericles received an education in music, rhetoric, philosophy, and military training, which prepared him well for life in a society that valued persuasive speech and intellectual skill.

He mixed in a circle of intellectual figures who encouraged his thinking during his formative years, and the philosopher Anaxagoras proved especially significant.

Anaxagoras promoted rational inquiry and doubt toward traditional myths, and Pericles absorbed ideas about reasoned argument and careful observation.

Other mentors such as Damon, Zeno of Elea, and Protagoras also influenced his outlook on politics and culture.

Herodotus likely visited Athens, and Socrates was alive at the time, but there is little firm evidence that either man was directly involved with Pericles’ intellectual circle.

Nevertheless, exposure to new approaches to science, politics, and art expanded his worldview and gave him the thinking skills that he later applied to leadership in a competitive democratic environment.

His entry into the political life of Athens

Pericles entered political life during the 460s BCE, as Athens consolidated its power after the Persian Wars, and he became associated with the democratic faction that championed greater authority for the assembly.

When he sponsored festivals and dramatic performances and launched major construction projects, he increased his popularity among ordinary citizens, and his support for reforms attracted the favour of the poor.

In 461 BCE, he backed the ostracism of Cimon, the leader of the conservative faction, after Cimon’s failed attempt to aid Sparta, and this action allowed the democratic party to dominate political life for decades.

He secured election as strategos, or general, almost every year from 443 BCE, and he probably held the office in earlier years as well.

Pericles used his office to introduce reforms that included payment for jury service, which allowed poorer citizens to participate in civic duties.

He also proposed a law in 451 BCE that restricted citizenship to those whose parents were both Athenians, and the measure defined civic identity more narrowly while provoking debate about its fairness.

How Pericles transformed Athens

Pericles oversaw an ambitious building program that turned Athens into the cultural centre of the Greek world, and he directed the use of funds from the Delian League treasury that had been moved to Athens in 454 BCE.

The construction of the Parthenon between 447 and 432 BCE became the most famous of these projects, and the temple honoured Athena was meant to advertise the city’s power and wealth.

Other structures such as the Propylaea were also built, and the sculptor Phidias created magnificent statues for the Acropolis that expressed Athenian pride in its achievements and empire.

Under his leadership Athens became a centre of literature and philosophy.

Playwrights such as Sophocles and Euripides wrote tragedies that explored politics, morality, and human suffering, and Aristophanes produced comedies that mocked contemporary figures and events.

Philosophers and historians, including Anaxagoras, found in Athens an environment that encouraged new ideas and debate.

As a result, the city gained a reputation as a hub of innovation and culture.

Pericles' controversial political views

Pericles pursued policies that tightened Athenian control over its allies, and he encouraged the collection of tribute from the member states of the Delian League while ensuring that Athens directed the league’s resources.

The allies gradually became dependent on Athenian protection, and many city-states viewed themselves as subjects rather than equal partners.

Hostility toward Athenian power increased, and resentment of the tribute system created lasting tension among Greece’s poleis.

Athens also established cleruchies in allied territories, and this policy further strengthened Athenian control.

He also promoted far-reaching democratic reforms within Athens, and he expanded the use of sortition for selecting officials.

He also provided state pay for civic participation. Critics accused him of manipulating the people, because he distributed public funds for festivals and construction projects, and conservative leaders argued that his measures weakened the influence of traditional aristocratic families.

His policies produced intense debate about the direction of Athenian democracy and the balance of power between elite and popular interests.

Pericles' scandalous private life

Pericles became the subject of controversy for his relationship with Aspasia of Miletus, because she was a foreign woman who lived with him as a companion and adviser.

Ancient sources suggested that she influenced his political decisions, but modern historians debate the extent of her influence.

Comic playwrights satirised him for his devotion to her, and conservatives condemned her as a corrupting figure who threatened traditional Athenian values.

Aspasia was even accused of impiety, and Pericles defended her in court against these charges.

Her household attracted leading thinkers such as Socrates, and it may have operated as an intellectual salon.

Pericles had earlier been married to an Athenian woman whose name is unknown, and she bore him two sons before their marriage ended in divorce.

His relationship with Aspasia produced another son, Pericles the Younger, and a special decree made this child legal.

Many citizens viewed the decree as a violation of established norms, and the decision intensified criticism of Pericles’ personal life.

Nevertheless, his political authority enabled him to shield Aspasia from legal attacks and public hostility.

His military leadership during the Peloponnesian Wars

Pericles adopted a defensive strategy when war erupted with Sparta in 431 BCE, and he advised Athenians to avoid pitched land battles, and he relied on their superior navy.

His plan required the rural population to move behind the Long Walls, and the fleet conducted raids along the Peloponnesian coast to pressure Spartan allies.

He believed that Athens, with its resources and naval power, could endure the conflict through patience and careful planning, and he maintained access to supplies through the port of Piraeus.

The strategy caused hardship for farmers who abandoned their land, and Spartan invasions repeatedly devastated the countryside.

Many citizens became frustrated with the long war and the destruction of their property, yet Pericles insisted that the city could prevail only by avoiding reckless engagements on land.

He trusted in the financial reserves and naval power of Athens to secure eventual victory over Sparta and its allies.

His leadership during the first years of the war reinforced his reputation as a cautious yet determined strategist.

The Plague of Athens and the tragic death of Pericles

A devastating plague struck Athens in 430 BCE when the city’s population crowded within the Long Walls, and the disease killed tens of thousands of people who were soldiers and sailors.

Thucydides described terrifying symptoms such as fever, intense thirst, and uncontrollable diarrhoea, and the plague caused chaos as citizens abandoned normal customs and lost faith in their leaders.

Modern scholars estimate that as much as one-third of the population perished.

Pericles’ famous Funeral Oration, delivered in 431 BCE after the first battles of the war, celebrated the virtues of Athenian democracy and honoured the city’s war dead, though the surviving text may not fully match what he said on that occasion.

Pericles himself contracted the disease in 429 BCE, and died soon after. He had already suffered the loss of both of his legitimate sons to the plague.

His death ended a period of steady and forward-thinking leadership that had guided Athens through decades of growth.

After his passing, the city struggled to find a leader with comparable authority and foresight, and the absence of such a figure contributed to Athens’ eventual defeat in the Peloponnesian War.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.