Blessings on your sewers and doorways: 15 obscure Roman gods you've never heard of

Roman religion often reached into unexpected parts of everyday life: on the battlefield, in temples, and over sewers, ovens, and compost heaps.

While Jupiter and Mars generally received attention during public rituals, many lesser-known gods commonly received quiet devotion behind closed doors or at the margins of farms and cities.

These obscure deities often show how Romans gave religious meaning to ordinary tasks and concerns.

1. Janus

Romans began every prayer and public ceremony when they invoked Janus, whom they generally believed oversaw all changes, including the start of wars, journeys, treaties, and calendars.

Since his name came from the Latin ianua, which meant 'doorway', his worship generally focused on doorways, both real and symbolic, and his two-faced image showed his authority over the passage of time, as one face looked backwards and the other looked forward.

The month of January (Ianuarius), which the second king of Rome, Numa Pompilius, had introduced, bore his name.

As a result, he generally became the first god to receive offerings in almost every religious ceremony.

According to early Roman tradition, Janus opened the path to the gods, which allowed communication between mortals and the divine.

His temple in the Forum typically displayed open doors during wartime and closed them when peace returned, so the state's relationship with Janus showed whether Rome was at war or at peace.

Romans also associated Janus with bridges, gates, and passageways, and his influence reached practical spaces like the Ianus Geminus arch in the Forum.

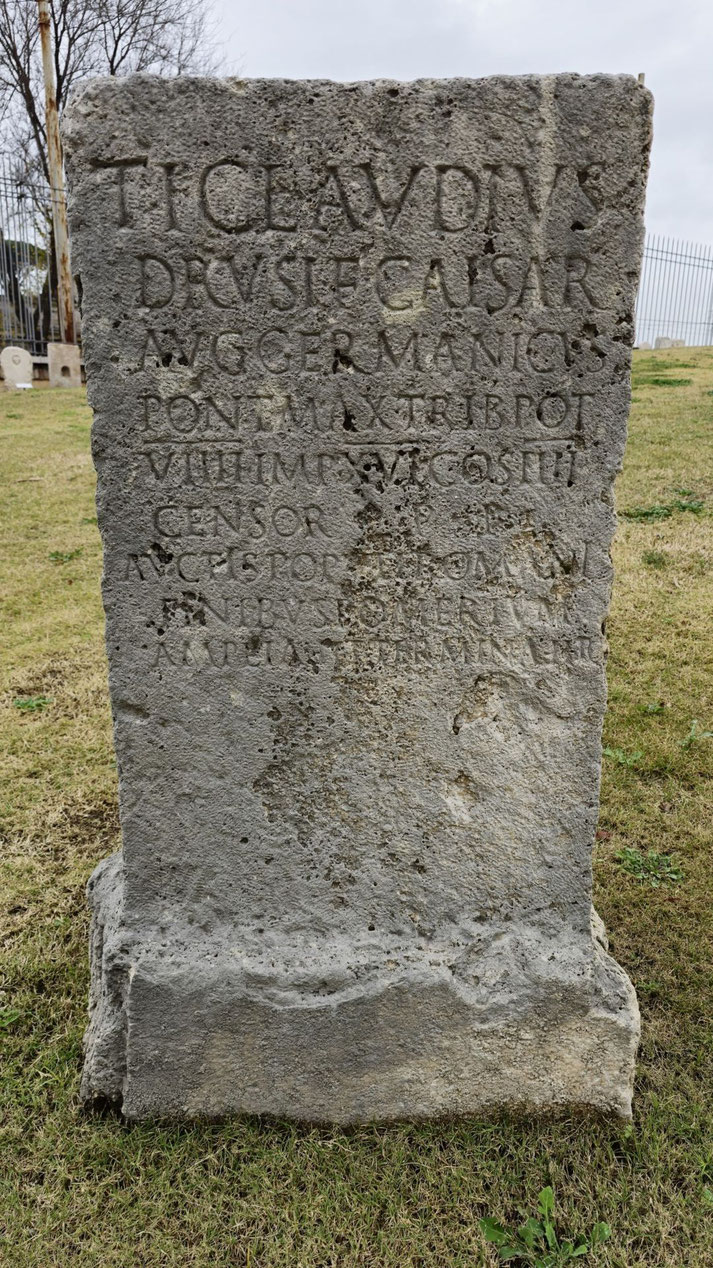

2. Terminus

Terminus protected boundary stones and property lines, whose presence protected the lasting and sacred nature of Roman land divisions.

Owners of adjacent plots traditionally met annually at their shared markers, which they decorated with garlands and gave offerings of wine, grain, or honey during the Terminalia festival, held each year on 23 February.

Rather than move his sacred stones, builders typically preserved them. For example, when construction began on the great Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, a Terminus stone that had already been on the Capitoline Hill could not be moved, so the builders constructed the foundation around it.

Livy (1.55.5) described this event as a good omen, showing that Rome's boundaries would remain secure.

3. Mithras

Mithras became widely popular among Roman soldiers who saw in his cult a disciplined, male-focused form of worship that matched the ideals of loyalty and secrecy and rested on a defined cosmic order.

His cult had likely arrived in the Roman world from the East, possibly through Cilician pirates or Persian mercenaries, and by the 2nd century CE, Mithraic temples, known as mithraea, had spread widely across the empire from Britain to Syria.

For example, mithraea were often constructed underground to evoke caves and to create a serious, enclosed space for initiates.

Inside these dim sanctuaries, worshippers, who typically dined together, participated in ritual stages, and celebrated the slaying of the bull, the tauroctony.

The seven grades of initiation, which included Corax, Miles, and Leo, formed a ranked system for moving up within the cult, so the cult of Mithras became especially appealing to the military, where a sense of order and secrecy combined with close male comradeship already held sway.

Women, however, were generally not permitted to participate.

4. Priapus

In Roman gardens and fields, Priapus often appeared as an odd-looking yet watchful figure whose exaggerated genitalia were used as symbols of fertility and warnings to intruders.

He originated in Greek folklore as a rustic fertility god from the town of Lampsacus.

His Roman version became more protective in purpose, and his statues often included inscriptions that threatened thieves with impotence or humiliation, so owners typically placed these statues at entrances to orchards, vegetable plots, and vineyards.

For instance, mocking texts such as the Priapea often portrayed him as someone who boasted about his punishments for trespassers.

A famous statue of Priapus from Pompeii, which excavators discovered near a domestic garden, bears such a threatening verse, so Priapus came to mark the boundary between cultivated land and outside danger, and he used shame and vulgarity to protect valuable produce.

5. Lemures

Within the darkness of Roman homes during May, householders often feared the return of the lemures, restless spirits of the unburied or forgotten dead who roamed the night in search of peace or vengeance.

To protect their families, the paterfamilias would often rise at midnight during the Lemuria festival on 9, 11, and 13 May, during which he walked barefoot through the house, tossed black beans over his shoulder, and recited set prayers.

Ovid’s Fasti describes these solemn rites in poetic detail.

As he performed the ritual, he rang bronze bells and avoided eye contact with other household members because he generally believed that the noise and silence worked together to drive away the ghosts.

So, the lemures generally remained excluded from normal ancestor worship, as their improper burials left them in a dangerous state.

Romans generally viewed them as dishonoured dead and as sources of disease, trouble, and family misfortune.

6. Orcus

Romans often feared Orcus as a cruel punisher of divine justice who dragged oath-breakers and wrongdoers into the underworld.

He did not rule the dead like Pluto. He operated as a punisher, and his name became commonly associated with punishment after death, especially in the rural parts of Latium and Etruria where caves and sinkholes bore his name.

For instance, shrines or inscriptions that stood near deep holes sometimes invoked his anger against those who lied under oath.

Orcus also appeared in Etruscan tomb paintings as a figure that snarled and had animal-like features.

Children often learned to behave because adults threatened that Orcus would take them away.

He lacked a central temple in Rome, but his influence often lingered in folk beliefs and local curses.

7. Bellona

Bellona had a prominent role in Roman war-making because her temple stood near the Circus Flaminius and the Senate often met there to conduct foreign affairs, especially declarations of war or negotiations with hostile powers.

Her appearance included a plumed helmet, a whip or sword, and a blood-smeared face, and it often caused violent excitement rather than strategy or honour.

Her priests, who were called bellonarii, cut themselves with knives during rites to stir divine energy.

Because Salii priests had sometimes invoked her alongside Mars in war rituals, her worship involved extreme behaviour and bloodletting.

So, soldiers often prayed to Bellona when they prepared for conflict, and they sought both victory and the emotional intensity needed for battle.

8. Cloacina

Cloacina stood for cleansing and sanitation, and she watched over the Cloaca Maxima.

Romans generally considered her guardian of the city’s great sewer system. Her name came from cloaca, which was the Latin word for drain, and her small shrine stood above a covered section of the sewer near the Roman Forum.

For example, some believed that Romans and Sabines purified themselves there after the conflict over the abduction of the Sabine women.

Over time, Cloacina’s identity blended with Venus, and her shrine bore symbols of love and peace.

Because Numa Pompilius was said to have visited her sacred enclosure during his religious reforms, she came to stand for more than sewage: she signified the cleansing of tension between peoples.

9. Sterquilinus

On Roman farms, those who spread manure or compost often gave thanks to Sterquilinus, a deity whose role revolved around decomposition and fertilisation.

Because his name came from stercus, which meant dung, and his cult had formed part of the rustic religion that focused on the cycles of decay and renewal that farmers needed for successful crops, Romans often treated the unpleasant parts of decay as vital for growth.

By contrast with modern attitudes, many saw no shame in a god of manure. In fact, agricultural writings had described the value of dung in careful detail, and they had presented Sterquilinus as a quiet partner in every season’s harvest.

He belonged to a class of minor helper-deities, including Seia and Tutilina, who governed specific agricultural tasks.

10. Fornax

Fornax received worship as the goddess of ovens and baking from Roman women who feared that poor cooking might waste their grain or upset household spirits.

Since during the Fornacalia each curia, a Roman voting division, held feasts in her honour and the city’s central calendar included her name and associated rituals, her cult turned daily bread-making into a sacred act.

For example, householders commonly prayed to Fornax so their loaves would not burn or underbake.

The Fornacalia was a feriae conceptivae, which meant a movable feast, and those unsure of their curia celebrated on the final day, known as the stultorum feriae or "feast of fools."

The religious calendar reminded all Romans that their food’s success depended on effort and the cooperation of divine forces.

11. Averruncus

To avoid divine anger or misfortune, Romans often prayed to Averruncus, whose name came from avertere, which meant “to turn away.”

His rituals mainly aimed to prevent disaster, illness, or disruption rather than attract blessings, especially in times when omens suggested supernatural danger.

Instead of calling on him with praise, they usually tried to deflect his attention. For example, chants in the fields asked Averruncus to take blight or hailstorms away.

Because he was often invoked alongside Robigus, the deity who guarded against wheat rust, his cult mainly focused on deflecting misfortune, not worship, and reminded people of how uncertain their fortunes could be.

12. Vejovis

Vejovis often appeared in Roman cult as a youthful, sometimes threatening figure who stood in opposition to Jupiter.

His statue on the Capitoline Hill showed a beardless youth who was armed with arrows and accompanied by a goat, and his rituals sometimes included sacrifices that looked like human offerings, though they used a goat instead.

Because Romans had often turned to Vejovis when plague spread or crops failed, his festivals indicated periods of instability or danger.

Livy wrote that people feared his favour could shift without notice. His temple on the Capitoline Hill was dedicated on 7 January and stood between those of Jupiter and Juno, perhaps to balance his uncertain role.

13. Laverna

Thieves and fraudsters often whispered oaths to Laverna, a goddess who presided over secrecy and deception.

Her shrine, which was located near the Porta Lavernalis on the Aventine Hill, was small and out of sight, matching her nature as a goddess of secrecy.

For example, those who swindled others in business often invoked her name as they pretended to act honourably.

Since Roman playwrights such as Plautus and poets like Horace had referenced her in their works to mock religious hypocrisy, Laverna showed how liars and hypocrites led double lives.

Romans knew that dishonesty existed even in sacred spaces, and her presence in their religious world acknowledged that deception needed divine management too.

14. Felicitas

Felicitas personified wealth and wellbeing. Unlike Fortuna, who stood for luck, Felicitas rewarded disciplined effort and moral conduct.

Emperors often invoked her to support their legitimacy, and coinage often showed her holding symbols of abundance, such as cornucopias or caducei.

Her cult grew during the imperial period. For instance, temples and altars pointed to her connection to stability and peace.

Because a temple to Felicitas had been dedicated in 19 BCE by Lucius Licinius Lucullus and she had often appeared on coins alongside Pax and Concordia, when people worshipped Felicitas, they implied trust in fair divine outcomes and showed that prosperity followed discipline and piety.

15. Silvanus

Silvanus guarded fields, forests, and boundaries, and his image, which showed him bearded and cloaked with a pine branch in his hand, appeared in rustic shrines at the edges of properties.

His worship was common among shepherds, farmers, and woodsmen, who asked him to protect crops, livestock, and groves.

For example, offerings of milk, grain, or fruit were often left for him on boundary stones.

Augustan poets like Virgil had often invoked him in pastoral verse, so Silvanus became part of daily rural life, ensuring safety in wild or uncultivated areas.

Unlike Jupiter or Mars, he watched over sheep paths and fruit trees. This showed that Roman divinity lived in grand temples as well as in hedgerows and forest clearings.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.