Blessings on your sewers and doorways: 15 obscure Roman gods you've never heard of

In the bustling streets of ancient Rome, where senators debated in the Forum and gladiators fought for glory in the Colosseum, the gods and goddesses of the Roman pantheon were never far from the minds of the populace.

While you may be familiar with the heavy hitters like Jupiter, Mars, and Venus, what about the lesser-known deities who governed the more peculiar aspects of Roman life?

Have you ever wondered who the Romans prayed to for a successful bread bake, or who they invoked to keep their boundaries secure?

What about the god responsible for manure and fertilization, or the goddess who presided over Rome's sewage system?

Prepare to journey into the divine oddities of ancient Rome as we explore the most obscure, strange, and downright confusing gods and goddesses you've likely never heard of.

1. Janus

Janus, the Roman god of beginnings, endings, and transitions, stands as one of the most intriguing figures in the ancient pantheon.

Often depicted with two faces—one looking forward and the other backward—he serves as a symbol of the dual nature of existence.

His visage captures the essence of life's constant flux, embodying the perpetual tension between past and future, and the eternal cycle of birth and decay.

In ancient Rome, Janus was not just a god to be invoked at the start of new ventures; he was deeply woven into the fabric of daily life and the Roman state.

His temple doors in Rome were kept open in times of war, signifying that the god was vigilant, watching over the Roman legions as they fought for the glory of the empire.

Conversely, during times of peace, the doors were closed, symbolizing a state of cosmic balance and divine protection.

He was ritually honored at the beginning of each month, and most notably, the first month of the Roman calendar—January—is named in his honor.

This practice underscores the Romans' view of time as cyclical, always returning to a point of origin that is both an ending and a new beginning.

Janus was also invoked during key life transitions, such as marriages and births, emphasizing his role as a guardian of thresholds, both literal and metaphorical.

His dual-faced image was a reminder that every ending is but a precursor to a new beginning, and that change, though often feared, is an essential aspect of human experience.

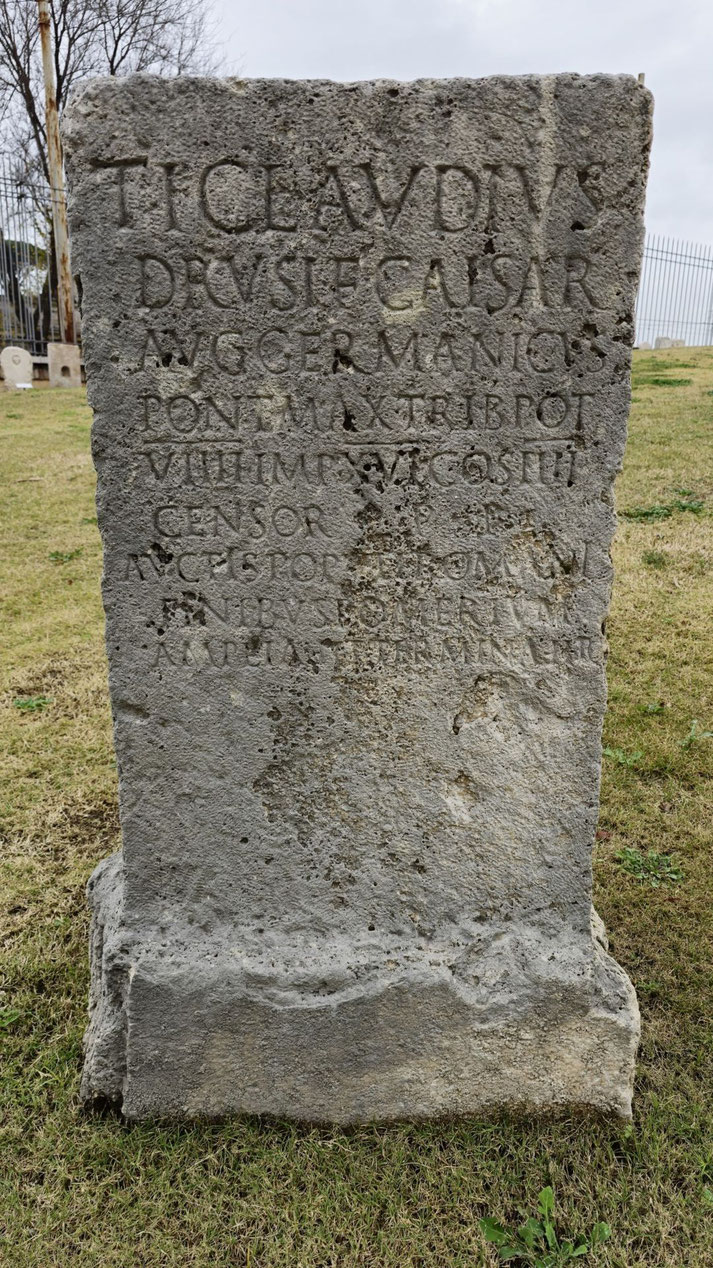

2. Terminus

Terminus was the god of boundary stones, a deity as stoic and unyielding as the markers that represented him.

Unlike other gods who were honored with elaborate statues and temples, Terminus was symbolized by simple stones or wooden posts, often placed at the boundaries of fields, estates, and provinces.

These markers were not just lifeless objects; they were imbued with the divine essence of Terminus, serving as both legal demarcations and spiritual safeguards.

The festival of Terminalia, held on February 23rd, was a communal celebration that brought neighbors together to honor their shared boundaries.

It was a day of both solemnity and festivity, where offerings of crops, honeycombs, and wine were made to the boundary stones.

This ritual was not merely a quaint tradition but a vital aspect of Roman social and religious life.

It emphasized the importance of mutual respect among neighbors and the sacredness of the land itself.

The rites performed during Terminalia were believed to invoke Terminus's blessings for a fruitful harvest and peaceful coexistence, reinforcing the idea that boundaries, both physical and metaphorical, were essential for harmony and prosperity.

3. Mithras

In the dimly lit underground sanctuaries of ancient Rome, away from the grand temples and bustling forums, a different kind of religious experience unfolded.

Here, in these subterranean chambers, the god Mithras was worshipped in a ritual shrouded in secrecy and mysticism.

Originating from Persian traditions, Mithras found a fervent following among Roman soldiers, who were drawn to the god's martial attributes and the promise of salvation.

The central image of Mithraism features Mithras slaying a sacred bull, a complex symbol interpreted in various ways but generally understood as a cosmic act of creation or renewal.

This act was not just a myth to be recounted but a mystery to be relived through intricate rituals, making Mithras worship a deeply experiential form of spirituality.

The cult of Mithras was exclusive and hierarchical, with initiates progressing through a series of seven grades, each associated with a planet and each requiring its own set of rites and tests.

This hierarchical structure mirrored the Roman military, making Mithraism particularly appealing to soldiers who found in it not just spiritual solace but also a sense of order and discipline that resonated with their own lives.

The secrecy surrounding Mithraic practices added an allure of the esoteric, a hidden knowledge accessible only to the initiated.

This sense of exclusivity and mystery made the cult an attractive alternative to the more public and communal religious practices of Rome, offering a form of individual spiritual advancement that was not readily available in the traditional Roman pantheon.

4. Priapus

This minor rustic deity, easily recognizable by his disproportionately large phallus, was a symbol of fertility in its most primal form.

While modern audiences might find the overt symbolism of Priapus amusing or even shocking, to the Romans, he was a potent emblem of life's generative forces, a protector of livestock, fruit plants, and gardens.

His image, often carved from wood and placed in gardens or at crossroads, was believed to ward off intruders and ensure bountiful harvests.

But Priapus was more than just a guardian of gardens and fields. His exaggerated form was a reminder of the raw vitality and vigor of nature, a force that was both creative and destructive.

In many ways, Priapus embodied the Romans' complex relationship with sexuality.

On one hand, he was celebrated for his virility and his role in ensuring the continuation of life.

Festivals in his honor involved ribald songs, dances, and jokes, celebrating the earthy and unrefined aspects of existence.

On the other hand, Priapus was also a figure of caution. Legends tell of his attempted assault on the nymph Lotis, only to be thwarted and humiliated when an ass's bray alerted the other gods.

This tale, often depicted in Roman art, served as a warning against the dangers of unchecked desire and the consequences of overstepping boundaries.

5. Lemures

In Roman mythology, the Lemures hold a unique and unsettling place. These malevolent sprits of the restless dead were believed to wander the earth, causing mischief and bringing misfortune to those unlucky enough to cross their paths.

Unlike the Manes, benevolent spirits of deceased family members who were honored and venerated, the Lemures were feared and sought to be appeased.

They were the unclaimed dead, souls without a resting place, and their presence was considered a sign of imbalance in the natural and divine order.

The Romans took the threat of Lemures seriously, dedicating specific rituals to appease these restless spirits.

The Lemuralia, or Lemuria, was a festival held on the 9th, 11th, and 13th of May, aimed at exorcising these malevolent entities.

The head of the household would rise at midnight, wash his hands three times, and walk through the house tossing black beans over his shoulder as an offering to the Lemures.

As he did so, he would chant incantations, imploring the spirits to leave the home and accept the offering as a substitute.

This ritual, performed in the dead of night, was a solemn affair, a stark contrast to the often joyful and communal nature of other Roman religious festivals.

It was a private rite, focused on the domestic sphere, emphasizing the Romans' belief in the sanctity of the home as a bulwark against chaos and disorder.

6. Orcus

Orcus was as a god of punishment and the underworld. Distinct from Pluto, who rules over the realm of the dead in general, Orcus is a deity specifically concerned with the punishment of oath-breakers and wrongdoers.

His very name, often used as a curse or an oath, evokes a sense of dread and foreboding, making him one of the most feared gods in the Roman pantheon.

Unlike other gods who might offer both punishment and reward, Orcus was singularly focused on the meting out of divine justice, a relentless avenger of broken promises and violated laws.

The concept of Orcus served a critical function in Roman society, which was deeply rooted in the principles of law and order.

Oaths were considered sacred contracts, inviolable bonds that held both individuals and communities together.

The fear of Orcus served as a powerful deterrent against breaking such oaths, reinforcing the social fabric and ensuring a level of trust and integrity essential for the functioning of the Roman state.

In this sense, Orcus was not just a figure of myth and legend but a very real presence in the daily lives of Romans, invoked in legal proceedings and social interactions as a reminder of the severe consequences of dishonesty.

7. Bellona

Bellona was a goddess of war, sister and female counterpart to Mars, the god of war himself.

While Mars was the embodiment of masculine martial prowess, Bellona brought a different, yet equally formidable, aspect of warfare to the divine table.

Often depicted in a chariot and sometimes brandishing a bloodied whip, she was a symbol of the ferocity and chaos of battle, a divine figure invoked to both instigate and sustain conflict.

Her temples were places where declarations of war were made, and it was said that a spear was thrown over a column in her temple to signify the Roman state's official entry into war.

Senators and generals would go to her temple to seek divine favor before embarking on military campaigns.

Her influence was so pervasive that her priests, known as Bellonarii, were known to gash their arms or faces and dance in an ecstatic frenzy, spattering their own blood as an offering to the goddess for victory in war.

This ritualistic shedding of blood underscores the Romans' understanding of war as a deeply sacrificial act, one that demanded both physical and spiritual offerings to ensure success.

8. Cloacina

Cloacina was the goddess of the Cloaca Maxima, Rome's great sewer system.

Initially a goddess of cleanliness and purity, Cloacina evolved to become the divine overseer of Rome's complex network of drains and sewage tunnels.

Her shrine, situated near the Roman Forum, was a testament to the Romans' pragmatic approach to divinity, where even the most mundane aspects of daily life were imbued with spiritual significance.

The Cloaca Maxima was an engineering marvel of its time, a crucial infrastructure that enabled Rome to grow into a bustling metropolis.

By overseeing this essential system, Cloacina became a goddess of public health and urban well-being, her veneration directly linked to the prosperity and functionality of the city.

In a society where the lines between the sacred and the profane were often blurred, Cloacina's unique domain made her an object of both civic pride and religious reverence.

Her presence served as a constant reminder of the intricate relationship between the physical and the divine, where even the disposal of waste was seen as a sacred act, overseen by a dedicated deity.

9. Sterquilinus

In the fertile fields of ancient Rome, where the bounty of the earth was both a livelihood and a divine gift, Sterquilinus held a unique and somewhat malodorous role.

Known also as Stercutus or Sterculius, he was the god of manure and fertilization, a deity whose domain might raise eyebrows today but was of critical importance in a society deeply connected to agriculture.

Derived from "stercus," the Latin word for dung, Sterquilinus was venerated for his role in transforming waste into nutrient-rich soil, a process essential for bountiful harvests.

In this capacity, he was not merely a god of refuse but a deity of transformation and renewal, embodying the cyclical nature of life and death in the agricultural realm.

The importance of Sterquilinus was deeply rooted in the Roman understanding of agriculture as a sacred act, a partnership between humans and the divine to coax life from the earth.

Farmers would offer prayers and perhaps small sacrifices to Sterquilinus, asking for his blessings on their compost heaps and manure spreaders.

This was not a trivial matter; the fertility of the soil was a direct determinant of the community's well-being, affecting not just food supply but also the economy and, by extension, the strength of the Roman state.

In venerating Sterquilinus, the Romans acknowledged the often-overlooked elements that were nonetheless crucial for their survival and prosperity.

10. Fornax

Overseeing the essential art of bread baking, Fornax was a deity whose importance might be easily overlooked in a pantheon filled with gods and goddesses governing grander aspects of life and nature.

Yet, in a society where bread was not just a staple food but a symbol of community and civilization, Fornax's role was far from trivial.

Her name, derived from "furnus," the Latin word for oven, reveals her specific domain, and her festival, the Fornacalia, was a crucial event aimed at ensuring that bread would bake properly throughout the year.

Held on February 17th, it was a festival where bakers and families would offer the first grains of spelt, a type of wheat, to be roasted in ovens dedicated to Fornax.

These rites were believed to propitiate the goddess and ensure a year of successful baking, a matter of both economic and social importance.

In a society where communal ovens were often the centers of neighborhood activity, the act of baking bread was seen as a cooperative endeavor, one that required both human skill and divine favor.

The festival was a communal affair, reinforcing social bonds and shared responsibilities, and Fornax, in her role as the goddess of ovens and baking, became a symbol of community cohesion and interdependence.

11. Averruncus

Averruncus was created to avert harm and ward off evil, Averruncus was less a god of something and more a god against something.

His name itself is derived from the Latin verb "avertere," meaning to turn away, and he was invoked in various rituals designed to deflect misfortune or prevent calamity.

Unlike other gods who had specific domains, physical forms, and elaborate myths, Averruncus was more of a function than a form, a divine action invoked to maintain the balance and harmony of both the natural and human worlds.

The role of Averruncus was deeply rooted in the Roman understanding of fate and fortune as mutable forces that could be influenced by both human action and divine intervention.

While the Romans had Fortuna, the goddess of luck, to bring about good fortune, Averruncus served as her counterbalance, a divine force invoked to keep bad luck at bay.

His presence was often felt in everyday activities, from agricultural practices where farmers would invoke him to protect their crops, to household rituals designed to ward off evil spirits.

In this sense, Averruncus was a god of the people, accessible and relevant in daily life, offering a form of divine insurance against the unpredictable twists and turns of existence.

12. Vejovis

Often depicted as a youthful god holding a bundle of arrows and accompanied by a goat, Vejovis is considered one of the lesser-known deities of the Roman religious landscape.

Traditionally invoked as a god of healing, he was also associated with the underworld and was considered a protector against sickness and evil.

His temple on the Capitoline Hill, one of Rome's oldest, attests to his ancient origins and the complex role he played in Roman spirituality.

Vejovis was not a god of grandeur or glory; rather, he was a deity turned to in times of need, particularly during plagues or periods of illness.

His association with the goat, an animal often used in purification rituals, underscores his role as a cleanser and purifier, one who could drive away the malevolent forces that brought disease or misfortune.

In this capacity, Vejovis was a god of the people, accessible and immediate, offering a form of divine solace to those in distress.

His temples were places of refuge, where the sick and the suffering could seek divine intervention to alleviate their ailments.

13. Laverna

Known as the goddess of thieves, cheats, and the underworld, Laverna was the patroness of activities that operated in the shadows of Roman society.

Far from being a marginal figure, she was a deity whose sphere of influence touched on issues of law, morality, and social order.

Her temples were often located near the outskirts of cities or in secluded areas, fitting for a goddess who presided over the hidden and the clandestine.

Laverna was not merely a symbol of unlawful activities; she was a complex figure who embodied the ambiguities of Roman society's relationship with law and order.

On one hand, her existence acknowledged the reality of crime and deception as integral, if uncomfortable, parts of the social fabric.

On the other hand, she served as a divine counterbalance, a figure who could be invoked to protect against the very activities she represented.

In this way, Laverna was a paradoxical deity, embodying both the problem and its potential solution.

Her dual role made her a subject of both fear and veneration, a goddess to be appeased rather than openly worshipped.

14. Felicitas

Felicitas was the goddess of good fortune and happiness. She was not just a deity to be supplicated in times of need but also one to be celebrated in times of joy.

Her name, derived from the Latin word "felix," meaning happy or fortunate, encapsulates her essence as a bringer of joy and prosperity.

Unlike gods and goddesses who governed specific elements or events, Felicitas had a more abstract and universal domain, making her a popular figure among a wide range of worshippers.

She was often invoked during public ceremonies and rituals aimed at securing the favor of the gods for the Roman people as a whole.

Her temples were places where citizens could offer prayers and sacrifices, not just for personal gain but for the prosperity of their community and nation.

In this sense, Felicitas embodied the Roman ideal of shared fortune, the belief that individual happiness was intrinsically linked to the well-being of the larger society.

Her veneration was a communal affair, a collective aspiration for peace, prosperity, and happiness that transcended personal desires.

15. Silvanus

In the verdant forests and untamed wilderness of ancient Rome, where the boundaries between civilization and nature were ever-shifting, Silvanus stood as a guardian and guide.

Known as the god of woods, fields, and boundaries, Silvanus was a rustic deity, far removed from the grandeur and politics of Olympus.

Yet, his role was crucial in a society deeply connected to the land, where agriculture was not just a means of sustenance but a way of life.

Often depicted with a sickle or a pruning knife, Silvanus was venerated as a protector of the farmer's fields, a deity who ensured the fertility of the soil and the safety of livestock.

In a society where land ownership and property lines were of utmost importance, Silvanus served as a divine surveyor, marking the limits of human habitation and ensuring that the sacred balance between man and nature was maintained.

His altars were often erected at boundary markers and crossroads, places where the human world intersected with the natural realm.

In this capacity, Silvanus was a mediator, a deity who facilitated the delicate relationship between civilization and wilderness, reminding Romans of the need for harmony and coexistence.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.