Christian martyrdom in the Roman Empire in the 2nd–4th centuries

Between the 2nd century AD and the time of Emperor Constantine the Great in the early 4th century, Christians in the Roman Empire faced periods of intense persecution and were even executed for their faith.

Those killed were ‘martyred’: a term that means they died for their beliefs. But why did these persecutions happen?

And why were the emperors themselves so determined to target people for their religion?

Ancient Roman attitudes towards Christians

The Romans were generally tolerant of religions, but only as long as they did not threaten Roman traditions or loyalty to the state.

Roman identity and civic life were deeply tied to worshipping the ancestral gods and the emperor’s genius (spirit).

Christians refused to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods or the emperor, which Romans saw as a shocking act of defiance against Roman culture and the favour of the gods.

In Roman eyes, this was impiety and even treason, since neglecting the gods could anger them and endanger the empire’s welfare.

Romans also viewed Christianity as an illicit superstitio (superstition) rather than a proper religion.

Christians met in secret gatherings, which looked suspiciously like unlicensed clubs (collegia): something Roman law forbade.

Therefore, by simply professing the name ‘Christian’, believers could be accused of a capital crime.

Christian persecutions in the second century

During the 2nd century AD, Christians suffered periodically through local persecutions and mob violence.

Emperors and governors held a variety of different attitudes towards them. In the 90s AD, Emperor Domitian was said to have executed or exiled individuals, including even his own cousin, on charges of ‘atheism’: a term implying they had adopted Jewish or Christian practices and refused the state gods.

This suggests that by Domitian’s reign, Christians were viewed with enough suspicion to warrant official punishment for impiety.

Importantly, before the mid-3rd century there was no formal empire-wide law specifically against Christianity.

The first known Roman policy came from Emperor Trajan’s instructions around 112 AD. He stated that Christians should not be hunted actively, but if accused and proven stubborn, they must be punished.

Trajan advised the governor Pliny the Younger that confirmed Christians who refused to recant should be executed, but those who worshipped the Roman gods could be freed, and anonymous accusations were not to be accepted.

This set a pattern. Christianity itself was effectively illegal, yet enforcement was inconsistent and often dependent on local attitudes.

Roman governors usually preferred to give Christians a chance to renounce their faith by offering sacrifices rather than make martyrs of them.

One proconsul in Asia Minor, annoyed by Christians who eagerly courted martyrdom, reportedly scolded a group: “If you want to die... you can use ropes or cliffs,” sending most away and executing only a few.

Then, under Emperor Hadrian (117–138) and Antoninus Pius (138–161), the situation remained relatively calm, though sporadic outbreaks occurred.

Hadrian reportedly advised governors not to entertain false accusations against Christians and to punish only clear violations of law.

Nevertheless, local hostility could erupt into violence. In AD 155, the beloved Bishop Polycarp of Smyrna was martyred after a mob cried out for the ‘atheist’ to be killed.

He famously refused to renounce his commitment to Christ and was burned at the stake.

The pattern of mob-driven persecution continued under Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161–180).

He was a Stoic philosopher and did not issue any known official decree against Christians.

However, some local authorities and crowds interpreted natural disasters or crises as the gods’ anger at Christians.

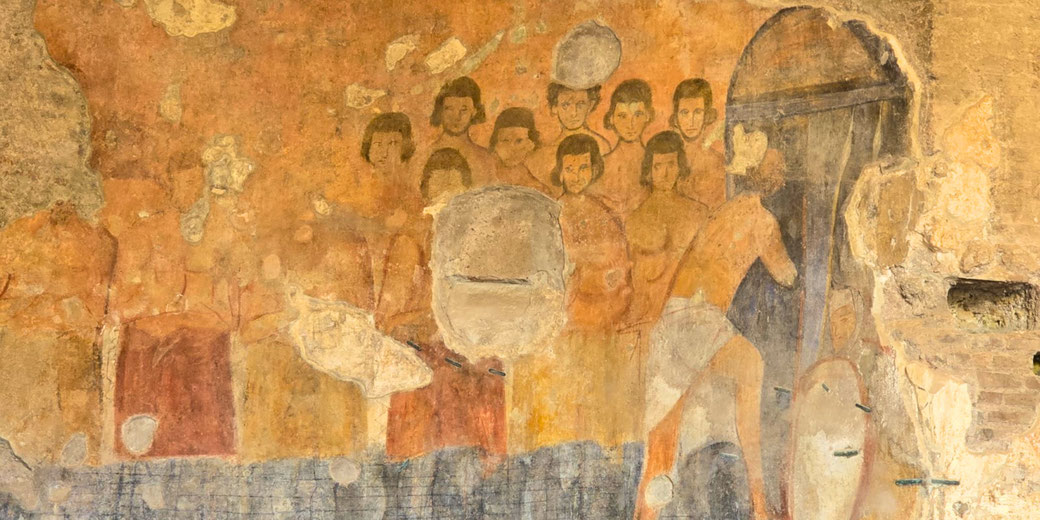

The most notorious case was in AD 177 at Lugdunum (Lyons) in Gaul. There, a violent outbreak led to many Christians being imprisoned, tortured, and killed.

A contemporary letter from the churches of Lyon and Vienne which has been preserved by Eusebius describes how believers were first attacked by an angry mob and banned from public spaces.

Then, they were put on trial by the governor. Some recanted under pressure, but others suffered unspeakable torments.

Among the martyrs was Blandina, a young, enslaved woman who endured repeated torture and inspired her fellow prisoners by professing, “I am a Christian, and we have done nothing wrong,” until she was finally killed.

The aged bishop Photinus of Lyon, who was nearly 90, was also beaten by the crowd and died in prison.

Eyewitnesses noted that though some believers did weaken and apostasise, many “through patience bore up against the whole force of the assaults”.

This appeared to encourage others to accept death rather than denying their faith.

In North Africa, around AD 180, twelve Christians known as the Scillitan Martyrs were executed in Carthage for refusing to swear by the emperor’s ‘genius’.

A few years earlier, the Christian apologist Justin Martyr had been beheaded in Rome under Marcus Aurelius’s rule after debating pagan philosophers.

Emperor Commodus (180–192) was relatively indifferent to Christians, and the church enjoyed a brief respite, aided perhaps by the influence of Commodus’s mistress Marcia who was sympathetic to Christianity, according to later sources.

However, around AD 202, under Emperor Septimius Severus, tradition holds that a law was passed forbidding conversion to Christianity and Judaism.

This led to another wave of persecution, especially in Egypt and Africa. The most famous victims were Perpetua and Felicitas.

They were young women in Carthage who were arrested for being new converts.

Perpetua’s written account vividly records her determination to remain faithful even as she cared for her infant child in prison.

She and Felicitas, who was a pregnant slave who gave birth just before execution, were eventually thrown to wild beasts in the arena.

Though the evidence for Severus’s specific edict is scant, it is clear that being a Christian remained dangerous in many provinces.

By the end of the 2nd century, apologist Tertullian would bitterly complain that whenever disasters struck, whether failed harvests, plagues, or floods, ordinary people cried, “Throw the Christians to the lions!” as a cure.

Christians had become convenient scapegoats for any misfortune.

The Decian Persecution (AD 249–251)

A major turning point came with Emperor Decius in the mid-3rd century. Decius reigned from AD 249 to 251, and a faced an unstable empire with external invasions and internal unrest.

Believing that Rome’s troubles were caused by a lapse in traditional religion, Decius resolved to revive the worship of the Roman gods on a grand scale as a way to restore unity and divine favour.

In AD 250, he issued an unprecedented edict that effectively targeted the entire population of the empire, including Christians.

The decree required everyone to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods and for the well-being of the emperor, to prove their loyalty.

These sacrifices had to be performed in the presence of a magistrate, and the participant would receive a certificate called a libellus as proof that they had obeyed the order.

Many such certificates from AD 250 have been discovered in Egypt, showing people affirming, “I have sacrificed to the gods,” and officials signing off on it.

For devout Christians, Decius’s edict posed a dilemma: their monotheistic faith forbade offering worship to any gods but the one true God.

Now they had to choose between abandoning their faith or risk punishments that could include prison, torture, or execution.

Unlike earlier persecutions, this was not a reaction to specific Christian crimes or refusals, it was a proactive loyalty test applied empire wide.

Decius’s aim was likely not to single out Christians in particular but to force unity in the empire through shared worship; however, Christians were his prime victims because they, unlike most of their pagan neighbours, could not comply in good conscience.

As such, the Decian persecution was the first truly empire-wide persecution of Christians, and it was severe.

While many Christians refused to sacrifice and were killed, many others gave in.

Contemporary accounts speak of large numbers of lapsi. These were Christians who lapsed by either sacrificing or obtaining fake certificates, many of whom later felt deep remorse.

Prominent church leaders became martyrs during this period: for example, Pope Fabian of Rome was arrested and died in prison in AD 250.

Other bishops, like Dionysius of Alexandria, went into hiding to evade capture.

Historian W.H.C. Frend estimates that roughly 3,000 to 3,500 Christians were killed during the Decian persecution, though the exact number is uncertain.

Decius’s edict was relatively short-lived because the emperor himself died in mid-251 AD during a battle.

Following his death, the edict lapsed and brought the persecution to an abrupt end. Christians who had survived breathed a sigh of relief.

In fact, Decius’s successor Gallus made no move to continue the campaign.

However, afterwards, debates raged in the Church about how to treat those who had failed the test: whether to welcome back the repentant lapsi or to hold a hard line.

In Carthage, Bishop Cyprian, who had himself gone into hiding during the worst of the danger, argued for allowing penitent apostates back after a period of penance, whereas some factions, like the priest Novatian in Rome, wanted to deny them re-entry to the Church.

Valerian’s Persecution (AD 257–260)

A few years of relative peace followed Decius’s reign until Emperor Valerian came to power in AD 253.

He initially also left Christians in peace. In fact, early in his reign, Valerian even had friendly relations with leaders like Cyprian of Carthage.

But the empire’s crises mounted, especially war with the resurgent Persian Empire, and by AD 257 Valerian’s policy shifted dramatically.

Perhaps seeking unity or divine aid in troubled times, Valerian launched a new persecution, this time with a very targeted approach.

Valerian issued his first edict against Christians in AD 257, focusing on the Church’s leadership.

This law ordered Christian clergy, which included bishops, priests, and deacons, to perform sacrifices to the Roman gods.

If they refused, they faced exile or other penalties. What is more, Christian gatherings in cemeteries, where they often worshipped and commemorated the dead, were banned.

The intent was to weaken the Church by pressuring or removing its leadership. Cyprian, the bishop of Carthage, was one of those exiled under this edict, although he continued to encourage his flock through letters.

Valerian did not stop there. In AD 258, he escalated with a second, harsher edict. This targeted Christians of high rank in Roman society.

Senators, knights (known as equites), and other prominent citizens who were Christians were commanded to renounce their faith and offer sacrifice to the gods.

Refusal meant that these nobles would lose their titles and property, and persistently refusing would lead to execution.

Christian women of high status who held to their faith could face confiscation of their property and exile as well.

Additionally, Christian officials or members of the imperial household were stripped of their office and enslaved if they would not comply.

As such, the persecution of 257–258 under Valerian proved deadly, as numerous Christians met their end, and the Church lost some of its most prominent leaders.

In Rome, Pope Sixtus II was captured while conducting a worship service in the catacombs and summarily executed in August 258.

Legend says that as he was led to death, his deacon Saint Lawrence quipped about joining him soon.

Indeed, Lawrence was killed a few days later by being roasted alive on a gridiron, according to later Christian tradition.

In Carthage, Bishop Cyprian, who had returned from exile, was arrested and bravely met his martyrdom: refusing to sacrifice, he was beheaded in front of a large crowd in September 258.

Other notable martyrs included Saint Denis, the bishop of Paris, and Saint Fructuosus, the bishop of Tarragona in Spain, among many others across the provinces.

Despite these blows, the persecution was cut short by events on the frontier. In AD 260, Valerian’s military campaign against Persia went disastrously. He was captured alive by the Persian King Shapur I, the only Roman emperor in history to become a prisoner of war.

Accounts say Shapur used the captive emperor as a footstool. Valerian never returned to Rome.

His son Gallienus succeeded him and immediately ended the persecution.

Gallienus issued an edict of toleration around AD 260 that ended the persecution and restored seized church property, but did not formally legalise Christianity.

As a result, the Church was in a state of official peace with the ruling authorities for the first time.

The remainder of Gallienus’s reign and the time of his successors in the later 3rd century were largely free of imperial persecutions, allowing the Christian community to recover, reorganise, and even grow in numbers and confidence.

The Great Persecution under Diocletian (AD 303–311)

By the dawn of the 4th century, Christians had become a significant minority in many parts of the Roman Empire.

Some even held positions of influence. The imperial crisis of the 3rd century had passed, and Emperor Diocletian, who ruled AD 284–305, brought a measure of stability through his reforms and the establishment of the Tetrarchy.

For most of his reign, Diocletian did not aggressively interfere with the Church. Christians lived relatively freely in the 280s and 290s, and it must have seemed that persecutions were a thing of the past.

However, traditional pagan sentiment at court, especially from Diocletian’s Caesar (junior co-emperor) Galerius, pushed for action against the growing Christian presence.

Galerius and others viewed the Christians as an affront that could no longer be tolerated, especially as the empire sought unity.

In AD 303, Diocletian’s government, persuaded by Galerius and alarmed by news that a priestess of Apollo’s oracle blamed Christians for hindering divine messages, decided to launch the most sweeping attack on Christianity ever attempted.

In February 303, just before the Christian Easter season, the first of a series of edicts was issued: all Christian churches were ordered to be demolished and their sacred books burned.

Christian gatherings for worship were outlawed. Furthermore, Christians were to be removed from government positions and lose normal legal rights. For instance, Christians could no longer appeal to the courts for justice, and Christian senators, knights, or palace officials would be stripped of rank if they persisted in their faith.

This meant that, legally, Christians were made outlaws once more in their own society.

When Christians did not crumble after the first edict, the imperial leadership intensified its efforts.

Later edicts in 303 and 304 took the persecution further. A second edict ordered the arrest of all Christian bishops, priests, and deacons.

Not long after, a third edict commanded that these imprisoned clergy be released if they agreed to offer sacrifice to the gods.

This essentially meant that they used torture or the threat of execution to force them to recant, or else leave them to die in jail.

Finally, in early 304, a fourth edict was issued which mandated that all inhabitants of the empire, Christian or not, must sacrifice to the Roman gods on pain of death.

This echoed Decius’s approach but with even more fanatical enforcement. Now every Christian man, woman, and even child was directly ordered to perform an act of pagan worship or face execution.

This campaign came to be known as the ‘Great Persecution’ and was the most severe and widespread in Roman history.

In province after province, churches were burned or torn down, and officials tried to make examples of Christians.

Eusebius of Caesarea, a church historian who lived through these events in the eastern Mediterranean, provides a harrowing eyewitness account.

He describes how, in city squares, Christian scriptures were consigned to bonfires, and how many believers chose to die rather than hand over holy writings or bow to idols.

Eusebius recounts that many brave Christians were subjected to terrible tortures, from scourging, racking, and burning, to being mutilated, yet they refused to recant.

At the same time, he honestly notes that “countless others succumbed at the first assault, cowardice having numbed their souls,” meaning a great number did give in and sacrificed under fear of pain.

The ferocity of the persecution was not enforced equally across the empire. For instance, in the Western provinces, which were ruled by Constantius under Diocletian’s direction, the enforcement was milder.

Constantius, it was said, disliked extreme measures and in Gaul and Britain he limited himself largely to destroying a few church buildings.

He did not execute Christians en masse or pursue the later edicts rigorously. Therefore, in places like Gaul, many Christians were spared the worst.

In Italy and Africa, where the other Western Augustus Maximian held sway, enforcement was somewhat firmer but still less bloody than in the East.

In the Eastern provinces under Diocletian and Galerius, however, the persecution was relentlessly harsh.

For instance, in Phrygia in Asia Minor, an entire town of Christians was reportedly burnt to the ground.

In Egypt and Palestine, arrests and executions were frequent. Some martyrs like Saint Catherine (in Alexandria) and Saint George became legendary for their sufferings around this time, although some of these legends are hard to verify historically.

Estimates of the death toll vary. One scholarly estimate is that about 3,000–3,500 Christians were killed in the Great Persecution, based on records and martyrologies, but other researchers argue the number could be in the tens of thousands across the empire over those years.

What is clear is that the Christian community endured intense trauma.

What happened to Christianity in the 4th century?

Ironically, even as the persecution raged, the four emperors leading the campaign did not remain united.

In AD 305, Diocletian and Maximian voluntarily retired from ruling, as per their tetrarchic plan.

Galerius and Constantius became the senior emperors. The very next year, 306, Constantius died in Britain and his troops acclaimed his son Constantine as Augustus.

Constantine had been sympathetic to Christianity as his mother Helena was a Christian and he immediately ended persecution in the territories he controlled.

In Rome, the population revolted against the cruel emperor Maxentius, son of Maximian, who had seized power there. Maxentius chose not to enforce the persecution edits in Italy.

Meanwhile in the East, Galerius continued to enforce the edicts until 311. By then, Galerius was deathly ill, and in April 311, Galerius finally admitted defeat.

He issued an Edict of Toleration (known as the Edict of Serdica), which conceded that Christians could once again worship freely, so long as they prayed for the well-being of the emperors.

Christians who had survived years of hiding and oppression rejoiced, and those who had weakened and sacrificed during the trials now sought forgiveness and re-entry into the Church.

Galerius died shortly after issuing his edict. In the power struggles that followed, Maximinus Daia in the Eastern regions briefly tried to renew persecutions in 311–312, but he was defeated by Licinius, Constantine’s ally.

Finally, in 313, the new Western emperor Constantine the Great met with Eastern emperor Licinius in Milan.

Together they issued the famous Edict of Milan, which granted full freedom of religion to Christians, and all others, throughout the empire.

The Edict of Milan also ordered that confiscated Christian property be restored and established a policy of official neutrality and acceptance toward Christianity.

Although Licinius later betrayed the policy and fought Constantine, the persecution era had effectively ended.

After nearly three centuries of intermittent persecutions, the martyrdom phase was over.

How Christians survived the killings

Throughout these centuries, Christians responded in ways that defined their faith and identity.

One key response was the embrace of martyrdom itself as a form of witness.

Rather than seeing martyrdom as a tragic failure, Christians came to view it as the ultimate testimony of faith and a way to imitate Christ’s own sacrificial death.

Martyrs were honoured as heroes in the Christian communities. Indeed, stories of courageous martyrs circulated widely in written accounts, collectively called 'Acts of the Martyrs'.

Martyrs were remembered annually on the anniversaries of their deaths with special prayers and commemorations.

This practice formed the basis for the later Christian saints’ feast days.

Another response of Christians was to engage in apologetics. These were reasoned defences of their faith addressed to pagan critics and Roman authorities.

As Christianity grew, educated believers rose to counter the misunderstandings and rumours that circulated about them.

In the 2nd century, figures like Justin Martyr and Athenagoras wrote apologies to the emperors, explaining that Christians were not, in fact, immoral or seditious, but law-abiding people who worshipped one God.

Justin’s First Apology, written around AD 155, patiently went through Christian beliefs and rituals, even describing the Eucharist and baptism, to show they weren’t heinous acts.

Athenagoras wrote A Plea for the Christians to refute the charges of atheism, cannibalism, and incest, which had arisen from misunderstandings of Christian terminology and practice.

Tertullian of Carthage, around AD 197, composed his own Apologeticus addressed to Roman governors.

In it, he pointed out the injustices of persecuting Christians who had done no wrong, famously asking why Christians were tortured “for the mere name” when no specific crimes could be proven.

He noted ironically that the same people who cried out against Christian 'atheists' actually had to admit Christians prayed for the emperor’s safety and the empire’s well-being.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.