Mamertine Prison in Rome, where Apostles Peter, Paul, and even Vercingetorix were held captive

Beneath the Capitoline Hill in Rome, a grim chamber of stone has survived for over two thousand years: the Mamertine Prison, which the Romans knew as the Tullianum.

It was the city's most well-known place of imprisonment during the Republic and early Empire. Though much altered by later Christian tradition and medieval structures, the core of the prison is still mostly preserved.

Its role in Roman legal and political life offers a brief view into how Rome used imprisonment as a tool of discouragement through a mix of public theatre and firm state control.

History of Mamertine Prison

Commonly linked to the 7th century BCE, the lower chamber of the prison may actually predate the formation of the Roman Republic.

This is because a series of burials containing the remains of a man, woman, and child, were unearthed on the site that may be as old as the 9th century BC.

However, the historical evidence does suggest that the use as a prison has a possible later origin in the earliest years of the Republic.

Roman tradition credited its construction to Ancus Marcius, the fourth king of Rome.

The upper chamber, which was added later, provides the most accessible entrance to the structure.

The prison was located next to the Gemonian Stairs, where executions often took place.

After sentencing, prisoners might be strangled in the Tullianum or publicly displayed on the steps outside as a public warning to others.

These executions were often carried out by an official carnifex, and the bodies were left on the stairs to rot, which was a form of damnatio memoriae for enemies of the state.

Unlike the sprawling carceres used in other ancient cultures, the Mamertine was a compact and secure space.

The underground design made escape virtually impossible.

Archaeological excavations in the modern era have confirmed much about the original structure.

The lower chamber, roughly 6.5 metres below street level, includes a round room with a curved roof and a small opening at the top.

It measures approximately 4.5 metres in diameter and was built with square-cut stone blocks made from local tufa rock.

Access originally came only through a hole in the floor of the upper level. Roman authors, including Sallust and Livy, described the prison’s harsh conditions.

In particular, Tacitus described secret executions out of public view, a detail later linked with the Mamertine by tradition.

The site remained in use for public imprisonment through the early imperial period, but it gradually lost prominence after the fourth century as Roman punishment practices evolved and the Christianisation of Rome changed how people thought about prison and punishment.

Famous Prisoners of Mamertine

Conditions inside the Mamertine Prison during antiquity were extremely harsh.

Ancient accounts describe a dark, airless chamber with no natural light or airflow.

The chamber’s small dimensions were made worse by damp conditions and poor hygiene, which made imprisonment both physically and mentally difficult.

Prisoners who awaited execution or trial could be held in isolation, chained and without basic comforts.

Since Roman citizens were not typically imprisoned as punishment, facilities like the Mamertine were used instead to hold enemies of the state prior to execution.

In some cases, this final punishment was carried out by strangulatio, a method of execution believed by some sources to have taken place in the lower chamber itself.

Most of the time during the Republic, Rome used the Mamertine to punish important foreign leaders and rebels.

In 63 BCE, Cicero ordered the execution of the Catilinarian conspirators after the Senate gave its approval, following the failure of their plot to overthrow the government.

While the exact site of their execution is still uncertain, it was traditionally believed to have occurred in the Tullianum.

Jugurtha, the defeated King of Numidia, died in the Tullianum after he had been paraded in triumph in 104 BCE and was reportedly starved to death.

Likewise, Vercingetorix, the Gallic chieftain who had been captured by Julius Caesar after the Siege of Alesia, spent six years in the prison before his public execution in 46 BCE.

Another notable prisoner was Simon bar Giora, the Jewish rebel leader who was displayed in Titus' triumph of 71 CE and executed shortly afterwards, likely when he was hurled from the Tarpeian Rock.

As such, the prison became a well-known site of political display: Roman victors paraded their defeated foes through the streets and deposited them into the Tullianum, where their fate would be used to reinforced Roman authority.

Saint Peter and Saint Paul in Mamertine

According to early Church writings, Saint Peter and Saint Paul both spent time imprisoned there before their martyrdom under Emperor Nero.

In fact, a spring in the floor of the lower chamber that is likely a natural feature from the original construction and possibly part of an older water system believed by some to be Etruscan, became associated with Peter’s miraculous baptisms of fellow prisoners and jailers.

The apocryphal Acts of Peter helped spread this tradition.

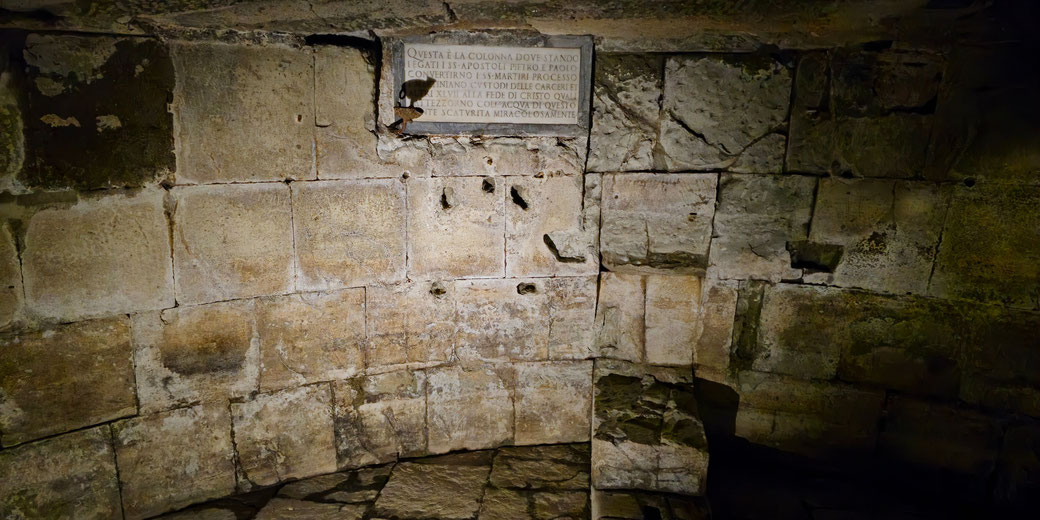

Perhaps the most famous Christian tradition about the Mamertine Prison claimed that Peter’s face was miraculously imprinted into the stone wall of the prison.

According to this account, and those who believe it, this happened when the apostle was thrown against the rock or pressed his face into it during prayer.

In fact, you can still see this when visiting the prison today. An area of the wall has been highlighted as the exact location of this miracle.

By the early medieval period, pilgrims visited the site as an important Christian site.

Churches were built over the structure, which protected it from demolition and allowed people to remember it.

However, reliable historical proof of Peter and Paul’s actually presence at this site is lacking.

Nevertheless, by the Middle Ages, the prison had become a popular stop for pilgrims travelling through Rome and was often incorporated into the religious tours of the city’s sacred sites.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.