What did early Christians actually believe before the Bible existed?

Long before anyone agreed on what counted as scripture, Christian communities were already living out their faith.

They listened to traveling teachers, exchanged urgent letters, and recited prayers that had never been written down.

The stories and teachings they kept guided lives and formed churches, even as the question of which writings truly belonged went unanswered for generations.

Oral Tradition and the Pauline Letters

Across the first century, followers of Jesus shared stories about his life, teachings, death, and resurrection by word of mouth.

Missionaries such as Paul, Peter, and others travelled from city to city. They established new churches as they taught orally and explained the meaning of Jesus’ death and return to life.

Since most early Christians could not read, and many communities had no access to written texts, they passed on core teachings by repeating creeds and singing hymns as narrative stories enriched their worship.

Simple declarations such as “Jesus is Lord” or summaries of key events, like the resurrection appearances listed in 1 Corinthians 15:3-8, helped maintain consistency across different groups.

Among the most important early sources of Christian belief were the letters of Paul, which circulated between churches long before the gospels were written.

By the mid-first century, churches in cities such as Corinth, Thessalonica, and Rome had already received Paul's letters, which addressed specific problems, explained theology, and outlined proper behaviour.

Paul's letters affirmed the exalted status of Jesus and his role in salvation, taught grace through faith, and described the expected return of Christ.

Some of these letters were read aloud in congregations and copied for use in other communities.

Regional Variations in Scripture Use

Within several decades of Jesus’ death, different communities began writing down his teachings and deeds.

The Gospel of Mark, likely written around the year 70 CE, was one of the first ongoing stories of Jesus' life. Other gospels soon followed.

Each presented a particular interpretation of Jesus’ mission, identity, and message.

Before church leaders settled on the four gospels known today, namely Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, many other writings also claimed to offer the truth about Jesus.

Texts such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter, and the Gospel of Mary provided different views, often with different emphases.

Some described secret teachings, others questioned traditional authority structures, and a few offered radically different views on the meaning of salvation.

Communities that used these texts did not necessarily see them as heretical. Many early Christians considered such writings accepted, especially if they supported their local customs and teachings.

Different regions preserved different collections. In Egypt, followers of Jesus sometimes used the Gospel of Thomas, which consists entirely of sayings attributed to Jesus, many of which have no parallel in the canonical gospels.

In Syria, some Christians drew on the Gospel of Peter, which includes a vivid and unusual account of the resurrection, such as a talking cross and a giant Jesus.

In Rome, bishops began to collect and recommend certain texts over others and they gradually reduced the list of approved scriptures.

Alongside these writings, early Christian beliefs drew heavily from Jewish traditions.

Most of the first believers were Jews who continued to observe the Sabbath, celebrate Passover, and read from the Hebrew Scriptures.

They interpreted Jesus as the fulfilment of ancient prophecies and saw him as the promised Messiah.

At the same time, Gentile converts brought different questions and cultural backgrounds, which led to discussions about circumcision, dietary laws, and the role of the Mosaic Law.

These issues appeared in the earliest theological disputes, many of which were resolved in local gatherings rather than by any central authority.

Did Early Christians Believe the Same Thing?

Until at least the mid-second century, there was no list of Christian scriptures accepted everywhere.

Churches depended on oral teachings, local letters, and written gospels that differed a lot in content and approval.

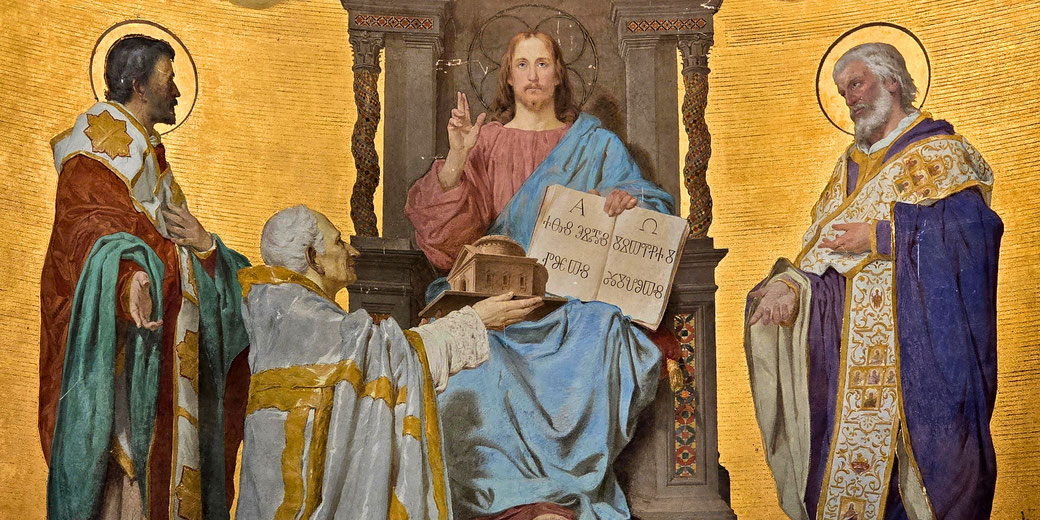

Bishops and theologians like Irenaeus of Lyons began arguing in favour of four gospels only, rejecting others as false or misleading.

His writings from around 180 CE demonstrate how some leaders tried to establish boundaries to protect what they saw as true doctrine.

However, his position did not receive universal agreement at the time, and considerable variation in accepted texts persisted throughout the second century.

Full agreement on the New Testament canon did not appear until the fourth century, when church councils such as the Synod of Hippo (393 CE) and the Council of Carthage (397 CE) listed the 27 books now found in the New Testament.

Even after these councils, widespread consensus developed only gradually.

Even before the canon was made official, early Christians already maintained a shared set of core beliefs.

They worshipped Jesus as the risen Lord, gathered in house churches for prayer and fellowship, baptised new members, and celebrated the Eucharist as a remembrance of Jesus’ sacrifice.

They believed that God forgave sins and offered eternal life as they awaited Christ’s return.

Their unity depended less on a fixed scripture and more on common practices, apostolic authority, and shared memories passed down within communities.

The variety of gospels, letters, oral traditions, and understandings reveals a world in which faith spread by word and deed, guided by local needs and anchored in lived experience.

Before the Bible existed as a book, the message of Christianity survived in people, places, and practices.

Faith survived through belief shared in voices, around tables, and proclaimed from city to city across the empire.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.