How the Carolingian Renaissance revived classical learning in Europe during the Dark Ages

In the late eighth and early ninth centuries, a burst of learning and creativity swept across western Europe from a brand new capital city at Aachen.

It transformed libraries and cathedral schools into centres where ideas were shared under the guidance of royal support and scholarly work in monasteries.

Latin texts that had been forgotten were recopied with great care, while new course plans took root to train clergy and administrators to read and write.

This lively blend of ancient classics and Christian devotion would help start Europe’s medieval university system.

What was the Carolingian Renaissance?

The Carolingian Renaissance was a period of cultural revival and thinking activity that occurred during the late 8th and 9th centuries under the rule of Charlemagne and his successors.

Centred mainly in the core regions of the Carolingian Empire, this movement aimed to restore learning, standardise religious practices, and improve administration through education and administrative reform.

The Carolingian court drew inspiration from the classical background of Rome and the Christian thinking traditions of the early Church, and fostered a renewed interest in literature, art, architecture, and theology.

This revival emerged through a deliberate effort supported by a group of scholars, monastic communities, and royal patronage, particularly under Charlemagne’s sole rule from 771 to 814.

The causes of the Carolingian Renaissance

Following the decline of the Western Roman Empire in the fifth century, Western Europe entered a prolonged period during which political splitting and reduced literacy limited the passing of classical knowledge.

By the early Middle Ages, much of the West had limited access to Latin texts and classical learning, which had been kept primarily in monastic scriptoria, though some traditions survived more fully in regions such as Ireland and parts of Italy.

In the Frankish territory, which had become one of the main powers in Western Europe, rulers increasingly relied on the Church to provide educated administrators and clergy.

The need for a more unified and literate elite became urgent under Charlemagne, whose conquests expanded his territory and required more effective systems of governance and religious consistency.

During Charlemagne’s reign, the cooperation between the Carolingian monarchy and the Church increased.

Key figures such as Alcuin of York, a Northumbrian scholar invited to Charlemagne’s court around 782, played a central role in designing educational reforms.

Alcuin, who directed the palace school at Aachen and later led the abbey school at Tours, also led changes to the Vulgate Bible, although his version did not become a final standard across Christendom.

He also helped promote a question-and-answer style of teaching that foreshadowed scholastic methods.

Along with others like Theodulf of Orléans and Paul the Deacon, a Lombard historian and liturgist, Alcuin formed part of a circle of thinkers tasked with restoring classical learning and improving religious instruction.

The movement aimed to preserve and correct existing texts, improve clerical literacy, and promote official theology rather than create new philosophical systems.

The Seven Liberal Arts

Within the Carolingian Empire, the promotion of education became a key policy instrument.

At Charlemagne’s urging, cathedral schools and monastic institutions were asked to set up courses focused on the liberal arts.

These schools taught the trivium, grammar, rhetoric and logic as basic skills to support accurate reading and interpretation of religious texts.

The quadrivium, which included arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy, was also taught to develop broader thinking skills.

Although the division of the seven liberal arts had earlier origins in the works of Boethius and Cassiodorus, it became more widely implemented under Charlemagne's reforms.

This curriculum drew directly from Roman models and was intended to create a learned clergy capable of instructing others and maintaining doctrinal conformity.

To support these goals, Charlemagne issued a series of capitularies, including the Admonitio Generalis in 789, which required educational standards and reforms across the empire.

The Admonitio declared that every bishop and abbot must provide schools for boys and ensure that both religious and secular learning were kept.

The king himself showed commitment to learning. He took lessons in Latin and Greek and encouraged his courtiers to do the same.

Although literacy rates remained limited, especially outside elite and ecclesiastical circles, the period did produce a noticeable rise in the number of manuscripts copied, kept, and studied.

Preservation of classical and Christian texts

The Carolingian Renaissance is especially known for its achievements in manuscript preservation.

Under the direction of Alcuin and other scholars, efforts were made to collect and copy ancient texts, both religious and non-religious.

Many classical Latin works that survive today, including those by Virgil, Cicero, Lucan, Orosius, and Pliny the Elder, were preserved thanks to Carolingian scribes who worked in monastic scriptoria at centres such as Fulda, Saint Gall, Corbie, and Tours.

Christian authors from Late Antiquity such as Boethius were also carefully copied and studied, which formed a key link to classical traditions.

These scribes reproduced texts and corrected errors that had crept in through generations of manual copying.

This careful process helped to preserve the integrity of many works and ensured these texts reached later generations.

An important change of the period was the development of a new style of handwriting known as Carolingian minuscule.

This script, which began in the late 8th century, featured clear, evenly spaced letters that made the letters easier to read and copy accurately.

It replaced the more irregular Merovingian and Visigothic scripts and became the standard for Latin manuscripts in the West.

The clarity of Carolingian minuscule contributed to the long-term survival and transmission of texts, and it affected the humanist minuscule developed by Renaissance scholars in the fifteenth century, which in turn shaped modern printed typography.

The widespread adoption of this script illustrates the real results of the changes started during Charlemagne’s rule.

Artistic and Architectural Achievements

In addition to the written word, the Carolingian Renaissance also influenced artistic and architectural developments.

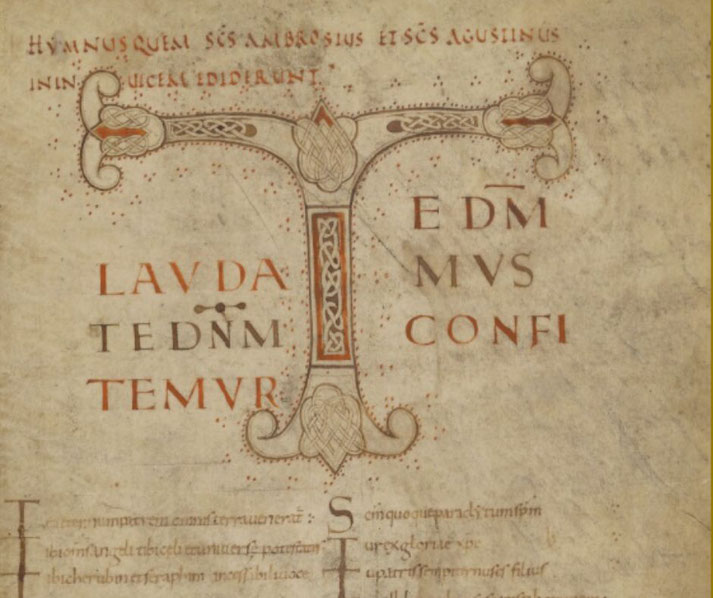

Inspired by Roman models and Christian symbolism, Carolingian art featured illuminated manuscripts, ivory carvings, metalwork, and frescoes that showed religious stories.

Monasteries such as those at Reichenau and Saint Gall became centres of artistic production, and manuscripts like the Godescalc Evangelistary and the Lorsch Gospels displayed detailed illustrations that combined classical forms with Christian themes.

These visual arts were closely tied to the Church’s mission to educate the faithful and convey sacred truths through images.

In architecture, Charlemagne sought to bring back Roman splendour and to show Christian unity.

The Palatine Chapel at Aachen, completed around 805, displayed elements of Roman and Byzantine design, with its octagonal dome and classical columns.

It became a model for later Carolingian churches and a visible sign of imperial power.

Uniform rules were also promoted through documents such as the Capitulare de Villis, which addressed estate management and royal administration.

Other church texts regulated religious services, vestments, and the treatment of relics, which reinforced correct religious practices and imperial control.

The consequences and significance of this period

Although the Carolingian Renaissance began to lose momentum following the death of Charlemagne in 814, many of its effects continued under his successors, particularly Louis the Pious and Charles the Bald.

Even after political fragmentation set in, the institutional and learning systems laid during this period shaped later medieval developments.

The survival of classical texts through Carolingian copies ensured that future generations in the High Middle Ages and Renaissance could access the writings of antiquity.

The curriculum established in Carolingian schools influenced the structure of medieval education well into the twelfth century.

By the 10th century, the weakening of central control and new attacks by Vikings, Magyars, and Saracens placed strains on the empire’s cultural institutions.

However, the influence of the Carolingian Renaissance remained in monastic traditions and shaped church administration; it also ensured that learning remained preserved across the region.

It established a model of Christian kingship based on religious devotion and learning and fostered a cultural environment that treated knowledge as a vital tool of administration and religious life.

Figures such as Dhuoda, who composed the Liber Manualis, a manual of moral instruction for her son in the 840s, demonstrate that this intellectual revival even reached some aristocratic women.

Through these lasting contributions, the Carolingian Renaissance holds a central place in the development of medieval Western society.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.