What were Marius' Mules? The revolution that created the Roman legions.

Empires rarely survived unless they changed how they waged war. In the Roman Republic, rising demands from foreign campaigns and internal power struggles led to a key military overhaul.

As a result, the everyday experience of the soldier changed dramatically, most visibly through the practice of carrying personal gear and rations, which earned these men the nickname "Marius’ Mules."

However, behind that name lies the story of how efficient supply management and social change suddenly transformed the Roman legions.

Who was Marius?

Born in 157 BC in the small town of Arpinum, Gaius Marius belonged to the equestrian class rather than the ruling elite.

Although his family held local influence, they lacked the traditional nobilitas, the elite status that opened the highest offices in Rome.

Through a combination of military distinction and political cunning, Marius worked his way up the cursus honorum, and his early military service under Scipio Aemilianus in Numantia gained him useful experience and recognition.

After holding the offices of tribune and praetor, Marius won the consulship for the first time in 107 BC.

He secured command of the war in Numidia against Jugurtha, and he bypassed many of the senators in the process.

During the campaign in North Africa, Marius relied heavily on his military expertise and gained further popularity with the Roman people.

His success against Jugurtha, and later against the invading Germanic tribes, solidified his status as a war hero and reformer.

By the time he held his unprecedented sixth consulship in 100 BC, his fifth in a consecutive sequence, Marius had become one of the most powerful men in Rome.

The need for military reform

By the late second century BC, the Roman army faced serious weaknesses. Rome’s military system relied on property-owning citizens to supply the manpower for its legions.

Recruits had to meet land ownership requirements to afford their own weapons and armour, which excluded the poorer classes from military service.

As a result, the eligible pool of recruits began to shrink.

Long campaigns in Spain, North Africa, and Gaul stretched the capacity of the traditional conscription system.

Many small landowners, which was the backbone of the old army, had lost their farms due to economic hardship, war, or debt.

Meanwhile, the expansion of latifundia, large estates owned by the wealthy, pushed many rural citizens into the cities, where they relied on the grain dole for survival.

In addition to manpower shortages, the Roman army needed better unity and training.

Citizen-soldiers, who fought only when called upon, often lacked the discipline and stamina required for long-term campaigns.

As a result, commanders struggled to raise forces quickly in emergencies.

Moreover, the inconsistent quality of troops made Roman victories less certain.

The Senate’s failure to reform the recruitment system allowed these issues to deepen until a military crisis forced change.

How Marius revolutionised the Roman army

Because he faced the threat of a Germanic invasion by the Cimbri and Teutones, Marius received special permission to recruit soldiers from the capite censi, the lowest census class, consisting of men with little or no property.

When he removed the landholding requirement, he created a new system in which any citizen could enlist.

The state now provided weapons and equipment for these soldiers, which meant greater consistency across the legions.

Marius also standardised training and organisation by creating cohorts as the primary battle unit, and he replaced the earlier manipular structure.

Each cohort consisted of roughly 480 men and could function independently on the battlefield.

This change gave commanders more flexibility and allowed for clearer chains of command.

In addition, Marius enforced consistent marching orders, weapons practice, and camp construction routines.

Soldiers took on a more professional nature and could serve for longer periods, sometimes up to sixteen years.

Marius also promoted the eagle standard (aquila) as the sole emblem for each legion, which created a stronger sense of loyalty and identity within individual units.

While earlier units may have used a variety of animal symbols, Marius gave the eagle greater importance.

Why were his new soldiers called 'Marius' Mules'?

With the recruitment of poorer citizens, the burden of military logistics shifted.

Under the old system, wealthy soldiers brought their own slaves and pack animals to carry supplies.

The new recruits lacked such resources. As a solution, Marius required each legionary to carry his own equipment, rations, tools, and weapons.

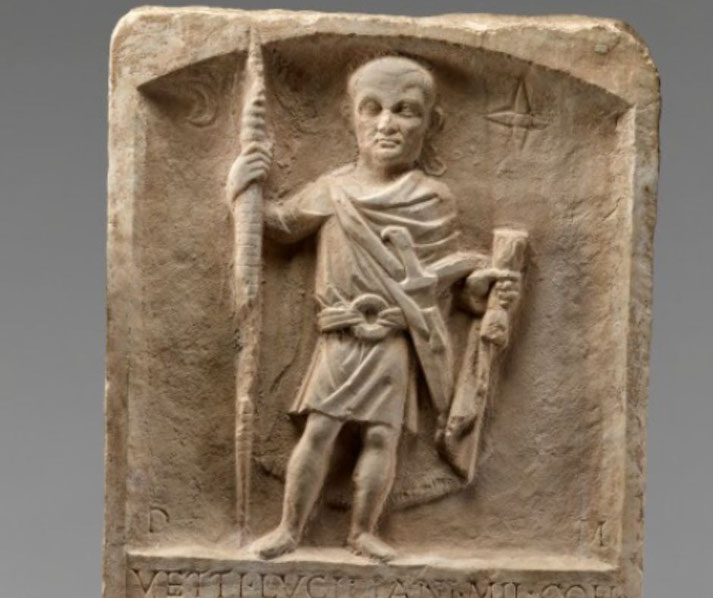

Each man marched with a furca, a wooden fork or pole, on which he slung his gear, including a cloak, cooking pot, food supply, entrenching tools, and a kit for constructing the nightly camp.

When the weight of weapons and armour joined the rest of their gear, this load often exceeded 30 kilograms.

The heavy packs gave rise to the nickname Muli Mariani, or “Marius’ Mules,” a term that some used mockingly.

Although the phrase appeared in later sources, it became a representation of the legionaries’ endurance.

By turning his soldiers into self-sufficient units, Marius reduced the army’s dependence on baggage trains.

His reforms allowed legions to move faster and maintain better security during marches.

In fact, the logistical changes contributed directly to the battle successes that followed in his campaigns.

How effective were these new troops?

In the short term, Marius’ new army delivered the results Rome desperately needed.

His reformed legions played a key role in defeating the invading Cimbri and Teutones between 102 and 101 BC.

At the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BC and the Battle of Vercellae the following year, the Roman army inflicted crushing defeats on the Germanic forces.

These victories ended the immediate threat and secured Marius’ military reputation.

The new cohorts operated with better discipline and teamwork, as their ability to build fortified camps each night ensured protection from surprise attacks.

In later decades, other generals adopted Marius’ methods. Sulla, Pompey, and Caesar all raised legions based on the Marius model.

The professional nature of the army gave Rome an unmatched military advantage in foreign conquests, from Gaul to the East, which all confirmed the value of Marius’ reforms on the battlefield.

The fundamental problems created by Marius' reforms

Although the short-term benefits appeared clear, the long-term consequences of Marius’ changes revealed serious problems.

Because he recruited from the poorest classes, Marius created soldiers who depended entirely on their generals for pay, plunder, and future land grants.

Their loyalty shifted from the Senate and the Republic to the individual who commanded them.

Generals now gained political leverage by promising rewards to their veterans.

Marius himself had to fight for land grants for his soldiers after their service, which set an example that others followed.

As armies became personal tools of political power, military leaders used their troops to threaten rivals and seize power in Rome.

Sulla's march on Rome in 88 BC was a turning point in which a Roman general used his army against the city itself.

A generation later, Julius Caesar followed a similar path when he crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC.

The roots of civil war can, therefore, be traced back to Marius’ decision to tie the soldiers’ welfare to their general’s success.

By undermining the Senate’s authority over recruitment and rewards, Marius unintentionally weakened the traditional structures of the Republic.

His reforms gave rise to a new political reality in which generals could ignore legal limits through military force.

Eventually, the professional army outlived the Republic and became the backbone of imperial rule under Augustus.

From a practical solution to a recruitment crisis, Marius’ reforms became a defining moment in Roman history.

The creation of Marius’ Mules saw the end of the citizen-soldier tradition and the beginning of a professional standing army adn it set the conditions for the collapse of the Republic and the rise of autocracy.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.