Juvenal: The savage satirist of Imperial Rome

During the early decades of the Roman Empire’s unification under the emperors, a bitter and sharp literary voice appeared from the shadows, dripping with disappointment and social anger.

His name was Decimus Iunius Iuvenalis, now better known as Juvenal. Born in the town of Aquinum in central Italy, likely during the reign of Emperor Nero around 55 CE, Juvenal gained recognition during the Flavian and early Antonine periods.

He spent most of his life under emperors whose reigns displayed decadent excess and heavy-handed repression under an expanding administration.

By the time he reached the peak of his writing, Juvenal had grown into one of the fiercest critics of Roman society that history has recorded.

Early Life and Moral Purpose

Juvenal came from a provincial equestrian family, which gave him enough wealth to access elite education, yet it proved insufficient for membership in the ruling class.

That position, perched just below the senatorial elite, infused much of his writing with disgust.

He saw himself as an ethical critic who could flay the city’s corruption and vulgarity, which emphasised its moral decay as he used verse as his weapon.

By the late first century, he had channelled that resentment into the creation of satura, a Roman poetic type that mocked vice and hypocrisy.

Critique of Roman Society

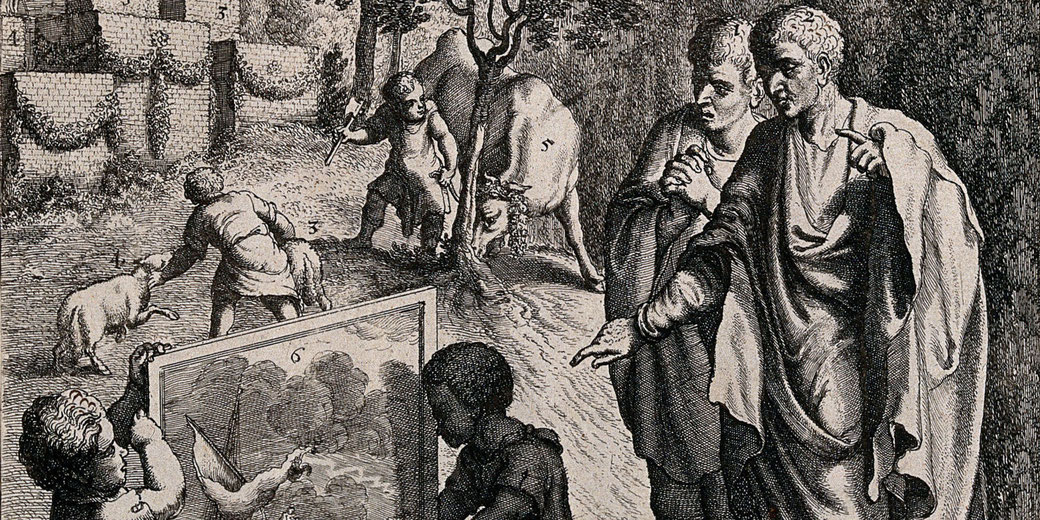

In his Satires, of which sixteen survive, Juvenal attacked almost every segment of Roman life.

His first book of satires was published in the early years of Emperor Trajan’s rule (circa 100 CE), and it lambasted the parasitic behaviour of flatterers, the degradation of women’s morals, the dangers of seeking patronage, and the criminality of the rich.

His poems accused Rome of having lost its republican virtues, of rewarding flattery and greed instead of honesty and dignity.

With intense exaggeration, he portrayed a Rome where no one could rise by merit and where foreigners polluted the city’s old traditions.

In Satire III, for instance, he constructed a tirade against Greek immigrants, which reflected his frustration at cultural change and perceived decline of native Roman customs.

Juvenal’s most famous phrase, panem et circenses (bread and circuses), is from his tenth satire, which ridiculed the Roman people for trading their political liberty for entertainment and handouts.

In it, he scorned how Romans no longer cared about their own freedom because they preferred theatrical spectacles and food subsidies.

Elsewhere in his works, he attacked corrupt magistrates, effeminate men, debased nobility, and gluttonous women. He spared no one.

His sixth satire, one of the longest, detailed what he believed to be the moral collapse of Roman women.

It listed every excess, from infidelity and drunkenness to obsession with gladiators and astrology.

By expressing such venom, Juvenal enjoyed both popular success and a growing threat of danger.

In particular, evidence suggests that his writings increasingly offended people in power.

One tradition that was recorded centuries later claimed that he was exiled to Egypt for offending an actor who held imperial favour.

Although modern historians questioned the reliability of this account, Juvenal’s scorn for court figures and entertainers certainly made his survival under strict rule uncertain.

Exile or not, he lived into the reign of Hadrian and continued to write and reflect on Rome’s flaws.

His later satires show less rage and more acceptance of fate. They examine themes such as the folly of excessive ambition and the emptiness of wealth.

Poetic Style and Lasting Impact

The literary style of Juvenal famously remained tightly controlled despite the intensity of his anger.

He composed his poems in dactylic hexameter, which was the traditional metre of epic poetry.

His technique combined rhetorical skill that intensified his exaggerations.

He often invented characters to be moral counterpoints or as examples of what he considered depravity.

Yet behind the grotesque images and sardonic humour lay real social criticisms: the lack of accountability among the rich, the weakening of Roman masculinity, the insecurity of the poor, and the growing gap between power and merit.

By the time of his death, sometime after 130 CE, Juvenal had completely transformed satire.

Later Roman writers praised his command of language but often recoiled at his harshness.

During the Renaissance and Enlightenment, European thinkers rediscovered Juvenal as a model of righteous anger.

His influence persisted in English literature through figures such as Samuel Johnson, Alexander Pope, and Jonathan Swift, who admired his courage and moral clarity.

In the Roman world, satire had begun as a method of gentle mockery. Juvenal turned it into a weapon in political battles.

His verses provide a stark and merciless window into the undercurrents of a Roman society that projected obscene wealth while seething with exploitation and vice.

Through Juvenal’s words, the façade of Rome’s imperial glory cracked open, exposing a city where corruption devoured decency and hypocrisy flourished openly in public life.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.