Was there a real, historical Holy Grail? Everything we know about this famous artifact.

The Holy Grail is best known as the cup said to have been used by Jesus Christ at the Last Supper and later to have caught his blood at the Crucifixion.

Over time, it became the focus of Christian legend and medieval chivalric tales, where knights, saints, and mystics pursued it through holy sites and spiritual trials.

Its origins, however, remain difficult to trace through historical evidence, and debate continues about whether it ever existed as a real artifact.

The earliest historical evidence of the Holy Grail

The earliest known mention of a Grail-like vessel occurred in the late twelfth century, when Chrétien de Troyes, a poet attached to the court of Marie de Champagne, composed Perceval, or the Story of the Grail, around 1180.

In this unfinished Arthurian romance, which survives in part in BNF fr. 12576, Chrétien described a mysterious object that the young knight Perceval witnessed being carried in a procession at the castle of the wounded Fisher King.

The vessel appeared as a golden dish that glowed with light, and while it clearly possessed magical qualities, it bore no connection to Christian relics or to Jesus Christ.

Chrétien did not use the term "Holy Grail," nor did he link the object to any known religious tradition.

Writers who followed Chrétien expanded the story and gave the vessel a Christian identity.

Around 1200, Robert de Boron, a poet from Burgundy, composed Joseph d'Arimathie, which was a verse romance that connected the Grail directly to the New Testament.

In his version, the Grail was the cup that Jesus had used at the Last Supper, and which Joseph of Arimathea later used to collect Christ’s blood as his body hung on the cross.

As such, Robert transformed the Grail from a fantastical object into a sacred relic with clear religious significance.

He further claimed that Joseph brought the Grail to Britain, where it became hidden and awaited discovery by worthy knights.

Robert's original poem has been lost, and the version known today survives in prose adaptations whose accuracy remains unclear.

Nonetheless, he laid the foundation for the idea of a spiritual lineage of Grail keepers, a motif that later authors developed further.

Subsequent medieval texts, particularly the Vulgate Cycle and the Post-Vulgate Cycle, expanded this tradition by mixing church teachings with Arthurian legend.

Composed between 1215 and 1235, possibly by authors influenced by Cistercian monastic ideals and spiritual themes, the Vulgate Cycle filled the Grail legend with ascetic values and Eucharistic symbolism.

These works presented the Grail as both a divine relic and a test of moral purity, guarded by heavenly forces and accessible only to the spiritually worthy.

Galahad, who is first introduced in these texts, was the ideal knight through his virginity and untainted soul rather than through feats of arms.

However, no known early church historian mentioned such a relic, and biblical texts offered only a brief mention of a cup used at the Last Supper, with no suggestion of future significance.

Early theologians, including Augustine and Jerome, made no reference to the Grail, which suggests that the tradition developed through literary invention rather than through ecclesiastical belief.

Lists of sacred objects from early church councils, such as the Council of Carthage in 397 and the Decretum Gelasianum, did not include any cup or vessel from the Last Supper among sacred objects.

The popularity of Grail stories during the Middle Ages was influenced by courtly ideals and monastic values as they tapped into the popular interest in relics.

As belief in the physical power of saints’ bones and relics spread across Europe, stories that placed sacred objects within quests and miracles found eager audiences.

By embedding the Grail into narratives that featured knights, kings, and pious hermits, authors gave spiritual weight to the ideals of chivalry and strengthened the belief that earthly deeds could lead to a divine revelation.

The Grail, in many of these texts, was a symbol of the Mass and divine grace and showed the influence of Cistercian mysticism and Marian devotion promoted by figures such as Bernard of Clairvaux.

Has anyone found the Holy Grail?

Several objects have been identified as possible candidates for the Holy Grail, yet none have withstood historical scrutiny.

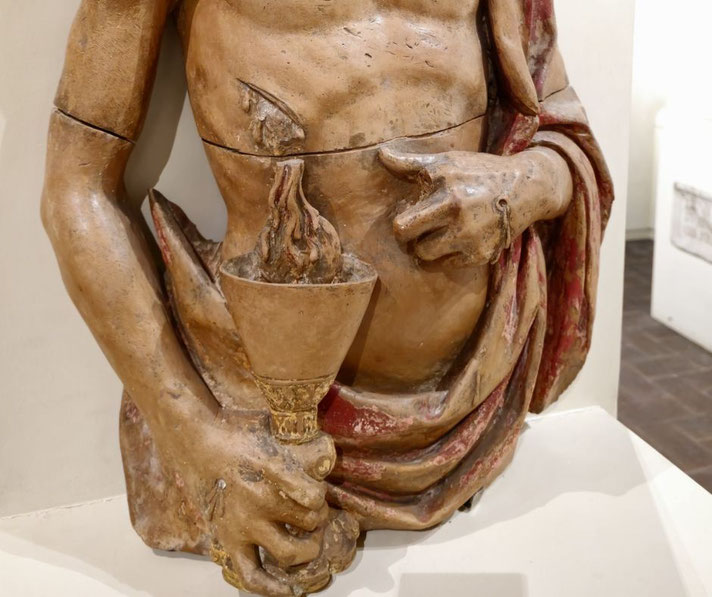

One of the most well-known is the Santo Cáliz of Valencia, which is kept in the cathedral of the same name.

It is a dark agate cup set in gold and decorated with jewels. Later, Church tradition in Spain holds that Saint Peter brought this cup from Jerusalem to Rome, from where it was eventually transferred to Christian communities in Spain during the Islamic conquest.

However, this tradition appeared in the medieval period and lacks support from early historical records.

Scientific analysis by Antonio Beltrán in the 1960s dated the central stone to between the 4th century BC and the 1st century AD, which places it in the correct era, yet no evidence confirms that it was ever in the possession of Jesus or his followers.

Another item that has drawn similar claims is the Chalice of Doña Urraca. This ornate 11th-century vessel sits in the Basilica of San Isidoro in León.

In 2014, researchers Margarita Torres and José Ortega del Río published a book in which they argued that this chalice originated in the early Christian communities of the Levant and was brought to Spain by Muslim traders or Christian exiles.

Their argument, which relied on Arabic writings and oral histories, attracted popular attention, yet historians have criticised the theory for its unproven claims and lack of direct documentation.

The chalice’s detailed design reflects medieval craftsmanship rather than the practical design of cups used during the Roman period.

Other Grail sites come from traditional stories rather than archaeology. In England, the Chalice Well at Glastonbury and the nearby ruins of Glastonbury Abbey have long been associated with Joseph of Arimathea and the Grail legend.

Pilgrims once believed that he brought the relic to Britain and hid it beneath the Glastonbury Tor.

These associations come from medieval monks who wanted to attract visitors and donations, which had no support in provable historical records.

In later centuries, stories that involved the Knights Templar and secret Grail guardians developed, but they reflected later romantic ideas and scepticism of religious institutions rather than medieval reality.

What if there's much more to this story?

The idea that the Grail legend might have acctually originated in even older religious traditions has drawn significant academic attention in recent years.

In particular, in pre-Christian Celtic myths, magical vessels with supernatural powers appeared in a range of Irish and Welsh stories.

These included the Cauldron of Dagda, one of the Four Treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann, which could feed an entire army without emptying, and the Cauldron of Annwn, which required the breath of nine maidens to boil and granted inspiration or rebirth.

In the Second Branch of the Mabinogi, the giant Brân the Blessed owned a cauldron that could resurrect the dead.

These stories, which were passed down through oral tradition, may have influenced the early conception of the Grail as a magical and mysterious object.

The transformation of these earlier themes into Christian narratives may have occurred gradually as monks and storytellers merged local traditional stories with biblical themes.

As medieval Europe experienced both a revival of classical learning and a rise in respect for relics, writers had both the intellectual tools and the popular interest to reframe older myths within Christian frameworks.

Some historians argue that the Grail became a symbolic vessel that took on the hopes and fears of people of the time, which was used as a spiritual goal for those disappointed by corruption in the world and longing for divine certainty.

Literary interpretations during the High and Late Middle Ages continued to expand the Grail’s meaning.

Some scholars have suggested that Parzival drew upon the influence of Cathar beliefs that circulated in southern France during the Albigensian period, although this interpretation remains speculative.

This version moved away from earlier Christian narratives and suggested that the Grail was an object of divine mystery accessible only to those who had purified themselves through prolonged suffering and rigorous pursuit of knowledge, a process that tested their endurance.

Ultimately, Von Eschenbach’s work introduced philosophical elements that aligned the Grail with concepts of divine wisdom and secret knowledge, which later writers were happy to adapt to their own circumstances.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.