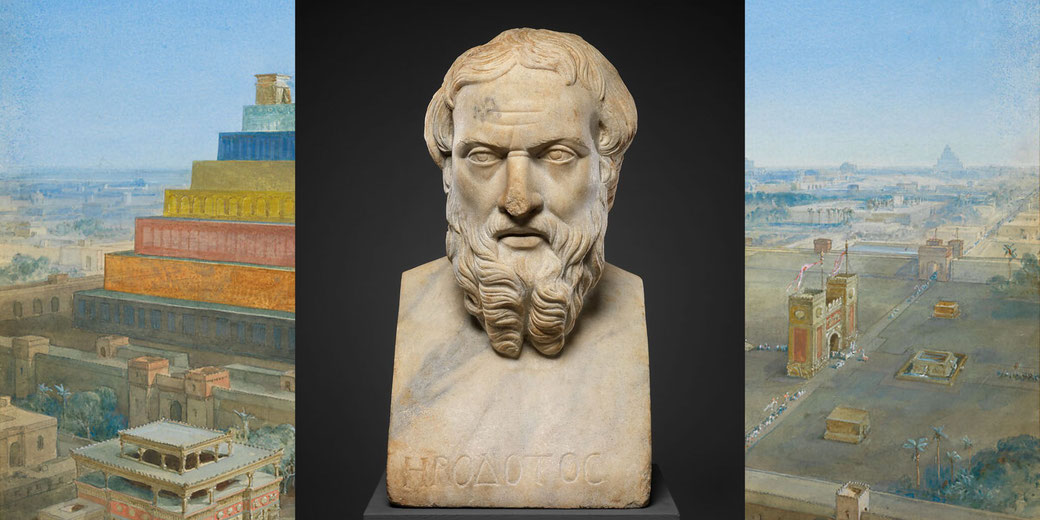

Who was Herodotus and why is he called the ‘Father of History’?

At a time when the memory of the Persian Wars still influenced Greek thinking, Herodotus undertook, what later turned out to be, a very important task.

He recorded the causes and conduct of the conflict, along with the aftermath of those conflicts. He gathered stories and evidence, and then raised new questions that earlier writers had ignored.

In fact, by writing The Histories, he created something new: a careful investigation into human affairs, which relied on careful observation and reflection on the past.

Later generations understood the value of his work and gave him a title that no one before him had earned. He became known as “the Father of History.”

The early years: How did Herodotus’ journey begin?

Around 484 BCE, Herodotus was born in Halicarnassus, a Greek city located on the coast of Caria in Asia Minor.

The city existed under Persian rule at the time, and its mixed cultural environment introduced him to the languages, religions, and political systems of both Greeks and Persians.

Halicarnassus was a port with active trade links and a strong naval tradition, which made it a natural centre where people exchanged goods, stories, and ideas.

Herodotus would have grown up hearing about distant wars, unusual customs, and the power of kings beyond the Aegean Sea.

After political unrest forced his family into exile, he travelled throughout the Greek world.

In Samos, he spent time in a thriving intellectual community influenced by Ionian traditions of natural philosophy and poetry.

Eventually, he arrived in Athens, where democratic debate and historical reflection became part of everyday life.

He listened to orators, attended festivals, and absorbed the pride that Athenians took in their victories over Persia.

That environment encouraged him to begin writing a record that explained how the wars between Greece and the East had come about and why they had unfolded the way they did.

Where did Herodotus go and what did he see?

During his travels, Herodotus visited many of the lands he later described in The Histories.

In Egypt, he observed temples and tombs, questioned priests, and described the unusual flooding cycle of the Nile.

He commented on religious rituals, burial practices, and the construction of great monuments.

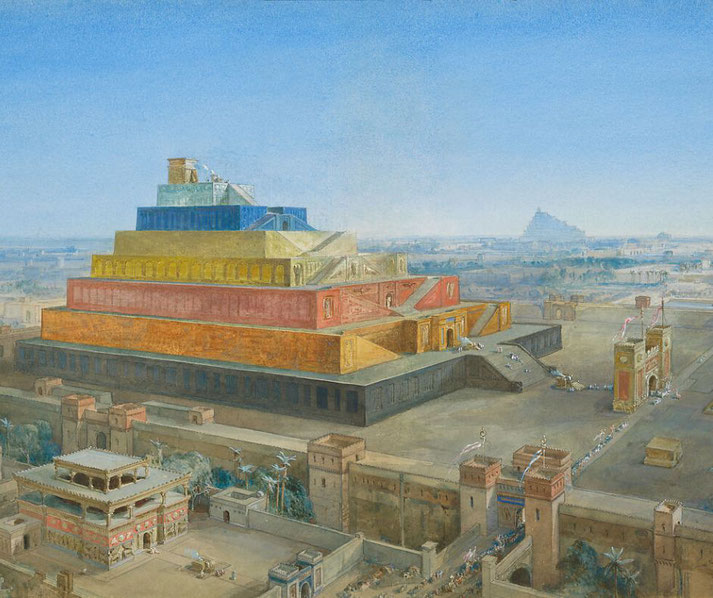

In Phoenicia, Babylon, and Syria, he described the size of cities, the nature of trade, and the impressive appearance of palaces and walls.

Further north, among the Scythians, he explored the nomadic customs of tribes who lived without permanent settlements.

He placed great importance on direct observation and often described what he had seen himself.

He also listened carefully to local stories and repeated them, even though he doubted their accuracy.

His interests included politics and warfare, but he also wrote about weather patterns, types of animals, systems of law, clothing styles, and dietary habits.

He recorded the beliefs of different peoples without dismissing them as foolish or inferior.

Thanks to this wide range of interests, he preserved the voices of many cultures whose views would otherwise have been lost.

The writing of The Histories

Over time, Herodotus compiled his research into a single work written in Ionic Greek.

Divided into nine books by later editors, The Histories covered a wide range across time and place.

It opened with the deeds of Eastern kings and traced the expansion of Persian power from the reign of Cyrus to the defeat of Xerxes.

Along the way, he examined the causes of revolts, the decisions of rulers, and the victories and disasters that influenced the world they understood.

He moved between personal stories and broader political developments, and he showed how small events led to great consequences.

Each section contained both true stories and thoughts about right and wrong. He included public speeches and prophetic dreams.

Herodotus inserted long side explanations, either to describe the customs of far-off peoples or to retell well-known myths in a new light.

At times, he warned his readers about how pride led to downfall, how divine will affected events, or how rulers lost power unexpectedly.

His goal was to avoid glorifying any single city and to explain why great events had happened and what lessons could be drawn from them.

Why is Herodotus called the ‘father of history’?

Herodotus earned his title because he created a new form of writing. Earlier poets had recorded stories of gods and heroes, but Herodotus focused on real events and real people.

He investigated past actions using first-hand accounts and physical evidence combined with logical thinking.

He examined cause and effect, traced the sequence of events, and considered the motives of individuals and states.

He explained his methods and offered alternative explanations when sources disagreed.

That spirit of inquiry was the beginning of historical thinking as a discipline.

His use of the Greek word historiē, meaning “inquiry” or “investigation,” gave later historians a model to follow.

Because he included several points of view and admitted when knowledge was limited, he set a standard for careful and fair research.

He presented history as something that could be studied and understood rather than simply accepted as fate.

Later writers such as Thucydides adopted and improved his method, but Herodotus provided the foundation.

His efforts showed that the past could be studied by looking at evidence and interpreted with care.

Herodotus and the Persian Wars: Why are his accounts so important?

Herodotus recorded the Persian Wars in greater detail than any other ancient author.

He described the background to the invasions, the major battles, and the responses of both Greek and Persian leaders.

He wrote about the bravery of Leonidas at Thermopylae, the cunning of Themistocles at Salamis, and the determination shown by the Spartans and Athenians in the face of overwhelming odds.

His accounts of the campaigns of Darius and Xerxes remain the most important surviving narrative of those events.

He also included information about the inner workings of the Persian court, the decisions made by the satraps, and the movements of large armies across unfamiliar terrain.

As such, he helped explain why the Persian advance failed and why Greek resistance succeeded.

Because he combined military history with the study of cultural traditions, he made it possible to study the war as more than a series of battles.

Later generations were able to understand both the immediate events and the larger conditions that influenced what happened through his descriptions.

Fact or fiction: Is Herodotus reliable?

Historians have often questioned the accuracy of Herodotus’ work. He included strange stories, exaggerated numbers, and unverified reports.

Some of his descriptions, such as giant gold-digging ants in India, or flying snakes in Arabia, sound implausible to modern readers.

He sometimes accepted local legends or repeated conflicting accounts without making a firm decision.

His information about distant lands depended heavily on hearsay and may reflect more about what people believed than what actually happened.

Yet Herodotus also showed caution and self-awareness. He frequently highlighted stories as being uncertain and acknowledged when his sources disagreed.

He explained his reasons for accepting or rejecting particular claims and his efforts to examine how people in different areas behaved.

Although later historians wrote with more precision, Herodotus showed others that events could be studied, compared carefully, and explained clearly.

People still find his writing useful for understanding the past and for seeing how people began to study history.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.