There's a big problem with ancient Egyptian chronology and we don't know how to fix it

The timeline of ancient Egypt, long seen as the centre of early world history, often falls apart under close examination when researchers try to match pharaohs’ reigns with archaeological and astronomical evidence.

To understand why records as large as the pyramids yield such unclear answers, we must examine how conflicting king lists, celestial cycles, and radiocarbon dating can all tell different stories.

Exploring how Egyptian chronology was made and why it remains debated shows the challenges of dating the distant past and how it affects our understanding of world history.

The ancient sources we use to date Egyptian events

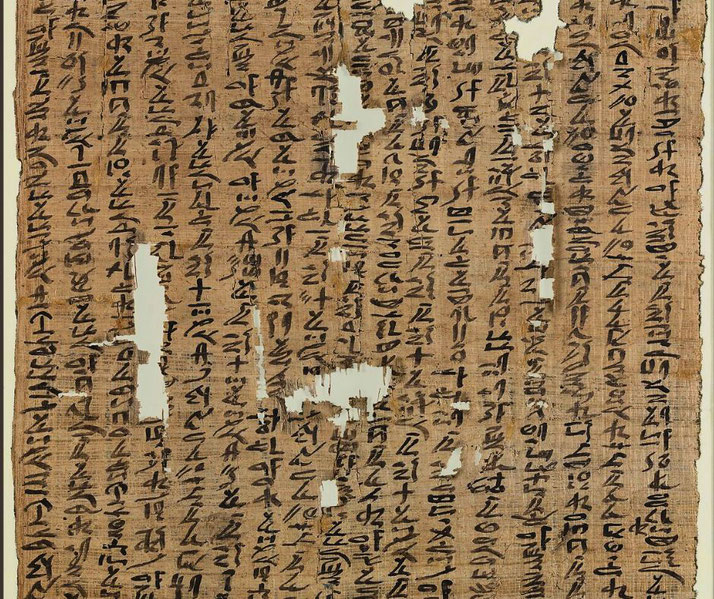

Manetho’s King List, written by an Egyptian priest in the 3rd century BCE, is still one of the most used sources when tryin to reconstruct the history of ancient Egypt.

This compilation provides a complete and ordered list of pharaohs and their reigns, organising Egyptian history into broad dynastic periods and helping to divide large spans of time in the empire’s 3000-year history.

Critics sometimes question its accuracy because of possible copying errors and later additions.

In addition to this list, large buildings like temples, tombs, and stelae provide supporting evidence.

Many inscriptions include dates or mention specific pharaohs, allowing historians to check events recorded in written sources such as Manetho.

Such inscriptions require careful evaluation, however, since they were often created with political or religious motivations.

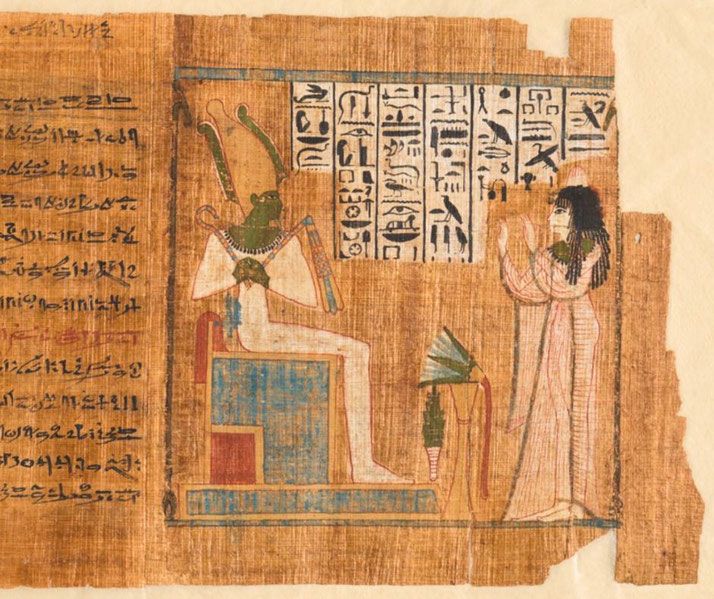

A third type of evidence comes from astronomical records. When ancient Egyptians observed sky events, especially the heliacal rising of the star Sirius (called Sothis by the Egyptians), they gained important time markers that modern astronomical calculations can verify.

Notably, a Sothic cycle lasting about 1,460 years has offered a means to tie historical events to specific dates, fixing the reign of Ramses II at 1279 to 1213 BCE.

Finally, radiocarbon dating introduced a scientific method for studying chronology beginning in the late 1940s.

Although it remains an important tool, it sometimes yields date ranges too wide to pinpoint specific events in Egyptian history.

It often has an error margin of 50–100 years, especially when used on older organic materials, making precise determination of reigns and events difficult.

When organic materials from archaeological sites are tested, radiocarbon dating provides a range of likely dates, adding another level of support or debate to established timelines.

The competing dating systems of Egyptian history

One of the most debated aspects of Egypt’s timeline is how the traditional, low, and high chronologies were established.

Each model assigns slightly different dates for key events and reigns, resulting in differences that can span decades or even centuries.

The traditional chronology has been widely accepted for many years and underlies many history books and educational materials.

It balances various sources without relying too heavily on a single piece of evidence.

In contrast, the low chronology assigns generally later dates than the traditional model.

Proponents of this model argue that certain period, especially the lengths of specific reigns or dynasties, have been overestimated in the traditional chronology.

By compressing these timelines, the low chronology often produces later dates for events or reigns compared with the traditional model.

The high chronology suggests that certain events or reigns occurred earlier than indicated by the traditional model.

Supporters believe that some periods have been underestimated in the traditional timeline.

A clear example of how different chronologies yield different answers is the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten.

This pharaoh introduced worship of the sun disk Aten and shaped our understanding of the broader historical and cultural context of his period.

According to the traditional chronology, Akhenaten’s reign is dated to about 1353–1336 BCE, whereas the low chronology places it slightly later, around 1349–1332 BCE.

These differences amount to just a few years, but the margin grows larger further back.

For example, by the Old Kingdom period, there can be up to 50 to 100 years’ difference between these systems.

The major discrepancies in Egyptian history

Perhaps the main disagreement concerns dating the Exodus, the biblical account of the Israelites’ departure from Egypt.

The pharaoh ruling during this event and its exact date remain uncertain, affecting both Egyptian and biblical timelines.

Differences in the lengths of individual pharaohs’ reigns, as provided by sources such as Manetho’s King List compared to archaeological inscriptions, complicate the issue.

The Pyramids of Giza, renowned symbols of ancient Egypt’s greatness, also have unclear dates. These structures, built as tombs for Khufu (Cheops), Khafre (Chephren), and Menkaure, represent the high point of pyramid construction and exhibit impressive engineering and architecture.

The most important and oldest of the three, the Great Pyramid of Khufu, was the primary reference for dating the entire Giza complex.

In the conventional timeline, constructing the Great Pyramid generally falls between c. 2580 and 2560 BCE during the Fourth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom.

Some scholars who use different interpretations of historical records or astronomical alignments propose slightly earlier or later dates.

For instance, certain low chronology interpretations suggest dates closer to c. 2570–2550 BCE. High chronology models lean toward c. 2590–2570 BCE.

Finally, the First (c. 2181–2055 BCE), Second (c. 1782–1570 BCE), and Third Intermediate Periods (c. 1069–664 BCE) pose the greatest dating challenges, as Egypt was politically split and official records remained scarce or missing.

The implications for world history

The timeline of ancient Egypt interacts closely with those of neighbouring civilizations.

Changing or questioning dates of major events in Egypt can affect chronologies of other ancient cultures.

For example, the ancient Anatolian civilization of the Hittites had diplomatic and military interactions with Egypt.

The Battle of Kadesh between the Hittites and the Egyptians under Ramses II is a key event in both cultures’ histories and is usually dated around 1274 BCE.

Egyptian chronology also influences understandings of cultures in the wider Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa.

Trade, diplomacy, and migration linked Egypt with regions as far as Mycenae in Greece and the Nubian Kingdoms to its south.

Shifting Egyptian dates might require revising trade patterns, cultural contacts, and political events in these regions.

Why finding an answer is important

Compiling the timeline of one of history’s most influential civilizations proved difficult given numerous sources, interpretations, and new methods.

Scholars continue to question, refine, and sometimes redefine the timeline, demonstrating that history changes with each new finding and analysis.

The debates surrounding Egyptian chronology highlight the necessity for careful thinking, interdisciplinary collaboration, and readiness to revise ideas when new evidence appears.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.