Who were the mysterious, ancient Druids?

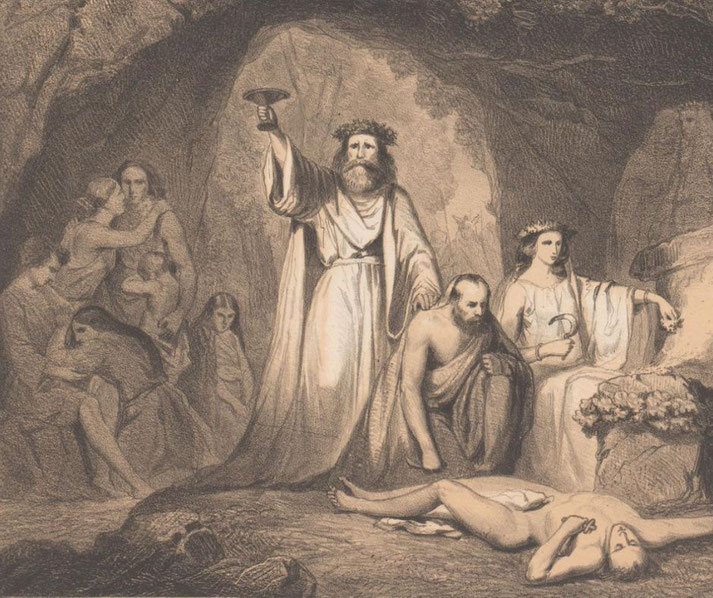

Druids were the priestly elite of ancient Celtic societies who surprised outsiders and made them uneasy. Greek and Roman authors recorded their existence, but the Druids themselves left no records.

As a result, nobody really knows where they came from, and people know little about their rituals or teachings.

What was a ‘druid’?

In the Celtic regions of Gaul, Britain, and Ireland, Druids held power in religious ceremonies, legal cases, teaching, and politics.

The word "Druid" likely derived from the Proto-Celtic dru-wid-es, often interpreted as "oak-knowers" or "strong seers," although this origin remains uncertain and scholars still debate it.

Julius Caesar described how Gallic Druids led religious rites, judged serious crimes, and trained students in lengthy oral instruction.

This is based upon the fac that he observed that Druidic teachings were passed down entirely by memory because they did not allow writing.

Caesar claimed that Britain was the centre of Druidic learning and that many Gallic students crossed the Channel to study there, though no physical or written proof confirms this claim.

Roman sources consistently presented the Druids as powerful figures whose influence reached every part of Celtic public life, and some claimed they had the authority to mediate tribal disputes or halt battles altogether.

What role did they have in society?

According to Pliny the Elder, Druids revered mistletoe and oak trees, which they used in rituals meant to heal the sick and promote fertility.

Strabo and Caesar wrote that Druids also carried out human sacrifices, including the well-known "wicker man" effigy in which victims were supposedly burned alive.

However, no archaeological evidence supports the existence of such effigies.

Tacitus wrote that Roman troops who advanced into northern Wales in AD 60, met a group of Druids who led local resistance on the island of Mona, now known as Anglesey.

As described in the account, the Druids raised their arms, shouted curses, and encouraged their followers while carrying flaming torches.

Suetonius Paulinus led the Roman assault on the island, but the campaign was interrupted, as the Romans soldiers were called to other areas of the country.

Overall, Roman commanders viewed them as religious leaders and dangerous political agitators who needed to be eliminated.

In later centuries, Christian monks in Ireland wrote down stories that featured Druid figures who worked as advisors to kings, judges in disputes, and experts in prophecy.

Medieval texts such as the Táin Bó Cúilnge described how Druids predicted battles, summoned fog, and cast spells.

Notable figures such as Cathbad appeared as wise and fearsome counsellors.

Although written long after the Druids disappeared, these sources kept alive the idea that they held secret knowledge.

Many of their magical traits likely reflected myth rather than memory, yet they appeared in tales that celebrated pre-Christian traditions and kept old beliefs alive.

What happened to the druids?

Under Roman rule, the Emperor Claudius banned Druidic practices in Gaul, viewing them as both dangerous and un-Roman.

During the campaign in Britain, the destruction of the Druid stronghold on Mona became a priority for Roman commanders who feared their ability to inspire resistance.

Over time, the Druids vanished from historical records. Some of their influence may have survived in the bardic schools and legal customs of early medieval Ireland, especially in the Brehon law tradition, which preserved detailed rules on status, restitution, and kinship.

However, while some scholars suggest that elements of Druidic culture endured in these systems, there is no direct evidence linking Druids to the formal codification of Irish law.

Roman writers sometimes separated Druids, bards, and vates, assigning them roles in philosophy, poetry, and divination respectively, though these categories may have varied across regions and time periods.

In early modern Europe, writers renewed interest in the Druids, although they often used guesswork instead of firm proof.

Early scholars such as John Aubrey and William Stukeley suggested that Druids built Stonehenge and knew astronomy, despite the fact that the monument dated from an earlier era more than a thousand years before historical Druids existed.

So, the association between Druids and Stonehenge began in the 17th century, based on imaginative interpretations rather than detailed study.

During the Romantic era, poets and philosophers reimagined the Druids as noble seekers of wisdom who lived in harmony with nature.

This version of the Druid bore little resemblance to the historical figures recorded in ancient texts, but it captured the imagination of a new generation.

Modern Druidic movements began with the Ancient Order of Druids in 1781, and later groups such as the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids, drew on this image rather than actual history.

The earliest of these groups were more like fraternal societies and only later adopted spiritual or nature-based themes.

Today, scholars face significant challenges in trying to reconstruct Druidic life. No inscriptions, tombs, or objects have been definitively linked to them.

Classical writers gave second-hand accounts that showed more about Roman ideas than accurate depictions of the original people.

Also, archaeological discoveries such as bog bodies, ritual deposits, and sacred enclosures suggest the presence of a priestly class in Celtic Europe, yet no direct evidence identifies those individuals as Druids.

Most of what is known comes from careful comparison between classical sources, Irish sagas, and Iron Age remains.

Therefore, the absence of contemporary Celtic accounts continues to limit modern understanding of their beliefs and practices.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.