The destruction of ancient Corinth: Rome's brutal display of power

In 146 BC, Roman troops under Lucius Mummius stormed the wealthy Greek city of Corinth, killed its defenders, enslaved its population, and levelled the entire settlement.

The destruction came at the end of years of worsening relations between the Roman Republic and the Greek states.

Rome appeared to have decided to eliminate the Achaean League’s influence and to deliver a brutal warning to the rest of the Greek world.

At the time of its fall, Corinth probably ranked among the most powerful and defiant members of the League, and its destruction was intended to crush all remaining hopes of Greek resistance.

Why was Corinth so important?

At the centre of southern Greece, Corinth controlled the Isthmus that joined the Peloponnese to the mainland and possessed two profitable harbours, Lechaeum on the Corinthian Gulf and Cenchreae on the Saronic Gulf, which enabled it to dominate both eastern and western maritime routes.

Through this control of seaborne trade and the Diolkos, a paved track over six kilometres long that allowed smaller ships and cargo to be hauled across land from one sea to the other that used wheeled platforms, the city had become one of the richest and most commercially influential centres in the Mediterranean, likely rivalled only by Delos and Rhodes.

From its high Acrocorinth, the city displayed its defences and its religious authority, while its temples and sanctuaries, most famously those of Aphrodite and Apollo, showed how wealthy it was.

Regular festivals, including the Isthmian Games held in honour of Poseidon, attracted pilgrims, merchants, and athletes from across the Greek world and contributed to Corinth’s identity as a religious and cultural hub.

Its population, which may have approached 70,000 inhabitants, benefited from high levels of urban development, with paved roads, monumental buildings, and public spaces that rivalled those of Athens and Alexandria.

For Rome, the city’s location and wealth made it an obvious target. Any city that controlled both strategic access and wide commercial flows would probably not be allowed to resist Roman interests for long without consequences.

The growing tensions between Greece and Rome

After Rome had defeated Macedon at Cynoscephalae in 197 BC and the Seleucid forces at Magnesia in 190 BC, it increased its presence in Greek affairs and began enforcing settlements in disputes among city-states.

Roman generals such as Quintus Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus claimed to be liberators, but many local populations viewed their actions as interference.

Greek resentment often grew as pro-Roman regimes replaced popular governments and Roman representatives issued interfering instructions.

Polybius, who had witnessed these developments firsthand, lamented the dishonesty and lack of foresight of Roman policy.

For example, in Sparta, internal strife gave Rome an excuse, which it used to impose reforms and assert control, while, in Athens, political realignments followed Roman interventions, which caused tensions among factions.

By the middle of the second century BC, resentment intensified among Greek elites, especially in the Peloponnese, where independence remained a powerful ideal.

The presence of Roman soldiers, diplomats, and allied forces added to the atmosphere of mistrust, which several political agitators exploited to call for resistance.

The formation of the Achaean League

Originally a small association of cities in northern Peloponnesus, the Achaean League expanded across the peninsula and developed a federal structure that largely allowed coordinated military organisation alongside unified economic and political decision making through elected assemblies.

Under the leadership of figures like Aratus and later Philopoemen, who lived from 253 to 183 BC, the League successfully opposed Macedonian rule and promoted collective autonomy.

One of its major victories occurred at the Battle of Sellasia in 222 BC, when League forces supported Antigonus III Doson of Macedon in defeating Sparta.

Eventually, as Rome weakened other Hellenistic powers, the League filled the gap and regained power in several disputes.

However, Roman officials grew wary of its growing influence. Tensions reached breaking point when Roman envoys demanded that the League exclude key cities, such as Sparta, from membership.

Diaeus of Megalopolis, who had become the League’s general in 147 BC, openly refused to accept Roman interference and began preparing for war.

By contrast, not all League members supported armed conflict. Some cities hesitated to send troops, and others warned of the likely consequences.

Still, Diaeus pushed ahead. The Achaeans crossed a line when they rejected Roman commands and refused to accept imposed settlements.

The League entered a conflict it could neither contain nor win.

The Roman war against the Achaean League

In 146 BC, the Roman Senate authorised war and appointed Lucius Mummius as consul to lead the campaign.

Although Mummius was not known for tactical skill, he had prior military experience in Hispania and commanded a well-trained army of over 23,000 infantry and 3,500 cavalry, drawn from previous campaigns in Greece and Asia.

By contrast, the Achaean League’s quickly raised army, which may have numbered around 14,000 infantry and 600 cavalry, likely lacked proper equipment and discipline.

First, Roman forces won a rapid victory at Scarpheia, located near Locris, which effectively broke the Achaeans’ will to fight and discouraged their troops.

After that defeat, Mummius advanced into the Peloponnese, where he encountered minimal resistance.

Cities surrendered rather than face the devastation that followed Scarpheia.

Diaeus attempted to regroup and defend Corinth, but internal divisions and his own failures in leadership made the situation worse.

According to Pausanias, he had poisoned his wife to prevent her capture before he took his own life in Megalopolis.

Eventually, Roman commanders, now unopposed, prepared to sack Corinth. The Senate had already made its intentions clear: the destruction of the city would serve as a warning to all who might consider challenging Rome again.

The Siege of Corinth

Roman troops surrounded the city and began siege operations in the spring of 146 BC.

Inside Corinth, defenders worked to reinforce the walls and repel attacks.

However, the lack of experienced leadership, combined with insufficient weapons and supplies, made effective defence impossible.

Roman engineers, who were far more experienced in siege warfare, brought up towers and rams that quickly damaged the outer defences.

Soon after the breach, Roman legions stormed into the city. Many soldiers killed fighters and civilians alike, looted temples, homes, and public buildings of valuable goods.

For example, statues by renowned artists such as Lysippos, religious relics, and manuscripts were packed for transport to Rome, where they later decorated public spaces and private villas.

Greek craftsmanship, once displayed proudly across Corinth, became property of Roman collectors.

As a result, Mummius ordered the population to be enslaved. Thousands of men, women, and children were likely taken in chains, sold to merchants, or distributed among allied states, and some ancient sources suggested figures as high as 60,000.

However, most modern scholars consider lower estimates, typically between 30,000 and 50,000, to be more likely.

Any remaining defenders were executed. No mercy was shown to those who had resisted.

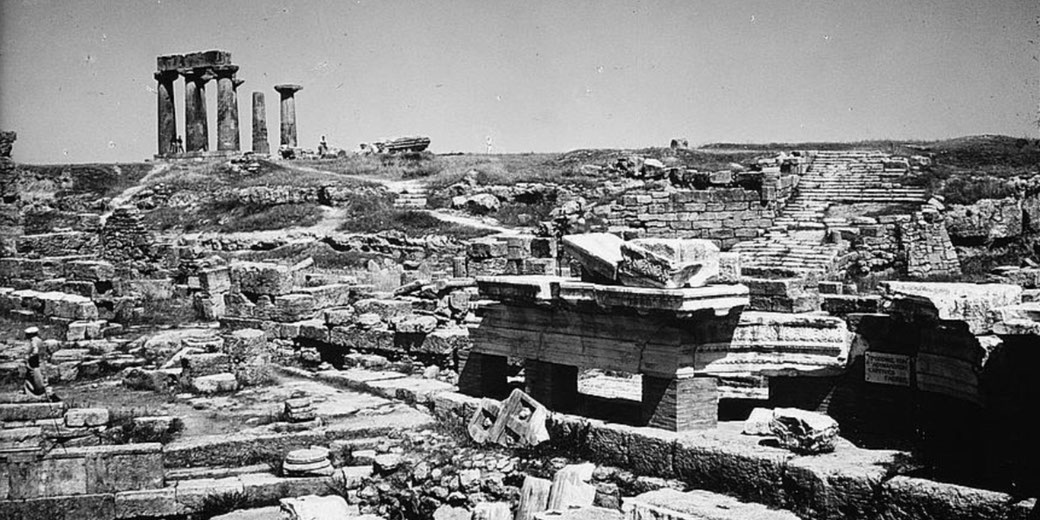

The relentless destruction of the city

After the looting had ended, Mummius carried out the Senate’s orders. Corinth was to be erased. Soldiers tore down buildings, temples were dismantled stone by stone, and fires engulfed entire neighbourhoods.

Religious sanctuaries, which had stood for centuries, were destroyed without hesitation.

Smoke from the city's fires blackened the sky above the isthmus for days.

Eventually, even the Acrocorinth, the city’s final stronghold, fell silent. Roads crumbled, aqueducts collapsed, and markets became rubble-strewn ruins.

Statues were melted for their bronze or carried off, while libraries and archives vanished in the flames.

Roman officers made no effort to preserve any part of the city’s cultural identity.

Although ancient sources claimed that the Senate had issued a formal decree prohibiting rebuilding, modern historians debate the nature of this prohibition.

It may have been a political or informal decision rather than a binding law. The land surrounding Corinth was added to the province of Achaea and was largely left deserted.

Greek authors such as Polybius mourned the loss, and Roman historians later recorded the event as a turning point in the Roman conquest of Greece.

Decision to rebuild Corinth

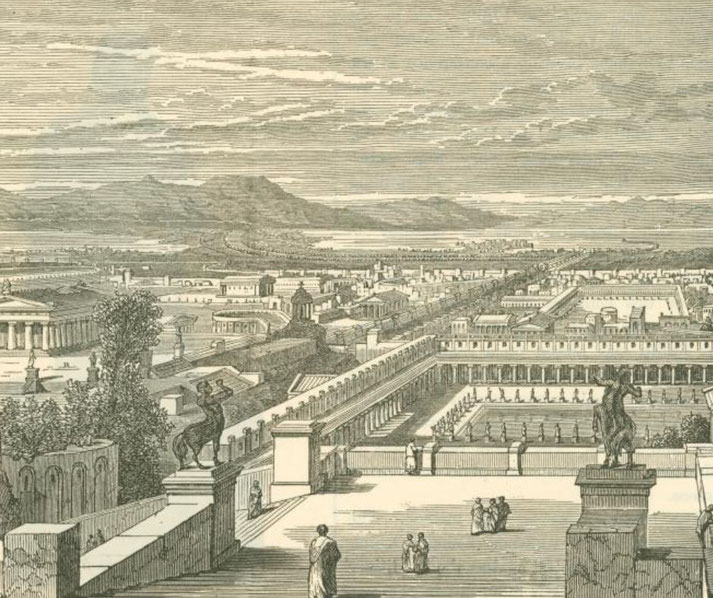

In 44 BC, Julius Caesar ordered the refounding of Corinth as a Roman colony. The city’s site, still perfectly placed for trade and defence, attracted settlers from across Italy.

Roman veterans, freedmen, and merchants arrived to rebuild what had been lost.

The new city, which was named Colonia Laus Iulia Corinthiensis, quickly became an important administrative and commercial centre.

Under Augustus and his successors, Corinth grew rapidly. Temples, roads, aqueducts, and public buildings, including the Fountain of Peirene and the Temple of Octavia, were constructed.

Many were in the Roman style, but they often incorporated surviving Greek elements.

Latin became the official language, yet Greek remained widely spoken among the population.

Religious life resumed, including old cults and new ones brought from across the empire.

By the middle of the first century AD, Corinth had largely regained importance.

The Apostle Paul visited during his missionary journeys and helped form a Christian congregation, later addressed in two of his epistles.

The rebuilt city never truly resembled the Greek polis destroyed by Mummius, yet it showed how Rome returned to exploit the same geographic and economic advantages it had once destroyed.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.