What, or who, REALLY killed Cleopatra?

Cleopatra VII was the final ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty and died in 30 BC under conditions that remain very unclear.

While Roman sources claimed she committed suicide, many modern historians continue to question this account. This is because her death occurred during one of the most unstable political moments in Roman and Egyptian history, and many of those involved had strong reasons to distort the truth.

How Cleopatra's life became a struggle for power

Cleopatra was born in 69 BC into a dynasty founded by Ptolemy I, one of Alexander the Great’s generals, and grew up in the Egyptian reoyal court that was caught up in conflict between rival factions that had already resorted to assassination to maintain power.

Her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes, ruled Egypt through the use of bribes to Rome and only retained his throne because Roman support shielded him from internal revolt and external threats.

After his death in 51 BC, Cleopatra was named co-regent with her younger brother Ptolemy XIII, in line with the legal customs of the dynasty, which demanded that male and female siblings share the throne, usually through formalised sibling marriage.

However, conflict within the royal court escalated quickly. By 48 BC, Cleopatra had been forced into exile by a faction loyal to Ptolemy XIII, who now held power in Alexandria.

She fled to Syria, where she raised a mercenary force and who prepared to return to Egypt by force.

Her fortunes changed dramatically when Julius Caesar arrived in Alexandria that same year.

Caesar worked to secure the eastern Mediterranean after defeating Pompey.

Cleopatra arranged to meet Caesar in secret and famously had herself smuggled into his quarters, possibly inside a rolled carpet.

This began a political alliance that would restore her to the throne and reshape Egypt’s connection to Rome.

After Caesar’s intervention and Ptolemy XIII’s death during the siege of Alexandria, Cleopatra resumed her rule and installed her younger brother Ptolemy XIV as co-regent.

However, she kept complete control of the government, while Ptolemy remained a figurehead.

Her relationship with Caesar produced a son, Caesarion, and she travelled to Rome with her son in 46 BC, where she stayed in Caesar’s villa on the outskirts of the city.

His assassination in 44 BC left her exposed and isolated. She returned to Egypt and swiftly arranged for the death of Ptolemy XIV, elevating Caesarion to co-regent and securing her power against internal threats.

Cleopatra had also received an excellent education and spoke multiple languages, including Egyptian, which distinguished her from previous Ptolemaic rulers who had relied solely on Greek.

In the following years, Cleopatra faced new uncertainty as the Roman Republic broke apart.

With Caesar’s assassins pursued by his political successors, a new alliance formed between Mark Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus.

Antony took charge of the eastern provinces, and in 41 BC, he summoned Cleopatra to meet him at Tarsus in Asia Minor.

She arrived in splendour aboard a barge, who was dressed as the goddess Isis, and secured his support through a range of personal and political discusions.

Their relationship soon deepened into a partnership that produced three children, Alexander Helios, Cleopatra Selene II and Ptolemy Philadelphus.

Together, they planned to restore Egyptian and Hellenistic influence under Roman protection.

The dramatic closing stages of Cleopatra's life

Antony spent the next several years strengthening power in the eastern Mediterranean, while Cleopatra supplied ships, soldiers, and wealth.

In 34 BC, they held the “Donations of Alexandria,” a public ceremony in which Antony distributed Roman-controlled territories to Cleopatra and their children.

Cleopatra was declared “Queen of Kings,” and Caesarion was named “King of Kings,” which provoked outrage in Rome.

Octavian used this moment to convince the Senate that Antony had betrayed Rome by aligning himself with a foreign queen and planning a rival eastern empire.

Political tensions broke into open conflict in 32 BC.

As Octavian prepared for war, Cleopatra equipped Antony with Egyptian naval and financial support.

Their combined fleet met Octavian’s forces at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, off the western coast of Greece.

Cleopatra’s squadron retreated from the battle in a sudden manoeuvre, and Antony followed her.

This allowed Octavian to claim victory and portray his opponents as deserters who abandoned their forces in the face of Roman resolve.

Over the following year, Cleopatra and Antony gathered again in Egypt, while Octavian slowly advanced through the eastern provinces, gathering support and getting ready for his final campaign.

In July of 30 BC, Octavian’s forces reached Alexandria. Antony. was convinced that Cleopatra had betrayed him and attempted suicide, but survived long enough to be taken to her.

Ancient sources describe his death in her arms, though the details are unclear and likely influenced by Roman traditions.

Some accounts also claimed that Antony was hoisted by rope into Cleopatra's mausoleum through a window.

Cleopatra then withdrew to a mausoleum she had prepared, which contained treasures and funeral goods, and was likely located near the royal palace close to the harbour.

There, she made several attempts to negotiate with Octavian, offering wealth, her throne, and even her life in exchange for clemency for her children.

However, Octavian refused all terms, and according to ancient writers, Cleopatra decided to end her life.

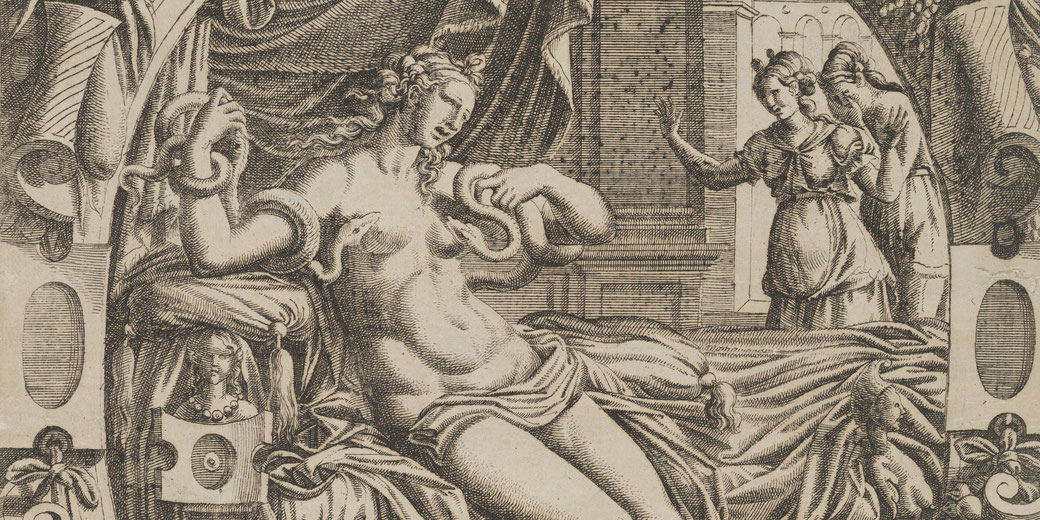

Roman sources describe how she smuggled a venomous snake, possibly an Egyptian cobra, into her mausoleum which she had hidden in a basket of figs.

Plutarch claimed that she was found with two puncture wounds on her arm, flanked by two dying attendants.

The story’s dramatic details that carried meaning for Roman audiences, who were fascinated by tales of royal suicide and exotic death.

The leading theories of her cause of death

Ancient accounts generally agree that Cleopatra committed suicide, but they offer conflicting versions of how it occurred.

Plutarch described a snakebite, while Dio Cassius mentioned the use of a poisoned hairpin.

Both accounts present the death as quick, yet they differ in practical detail. Roman authors had little direct knowledge of what happened inside Cleopatra’s mausoleum, as Octavian’s men only arrived after the event.

Therefore, their stories rely on political messaging based on rumour and faulty assumptions.

Modern historians question the snake theory for several reasons. Egyptian cobras are large, difficult to conceal, and unlikely to kill three people simultaneously in a short time.

The process of bringing such a dangerous animal into a guarded and carefully watched area also raised doubt.

Moreover, no reliable eyewitness described the moment of death. The meaning of the asp, which was more a picture of pharaonic power and royal status, made the story appealing to Roman propagandists who they framed her death as noble but exotic.

A more plausible explanation involves the use of fast-acting poison. Cleopatra had access to some of the most advanced medical and pharmaceutical knowledge of the ancient world, as Alexandria remained a centre for science and medicine.

Texts on poisons preserved in the Mouseion and Library of Alexandria may have informed her methods.

Writers such as Galen and Pliny the Elder described various poisons known to produce painless and reliable death.

So, Cleopatra may have tested these in advance and selected a method that would allow her to die with control and dignity.

Other historians argue that her death may not have been voluntary at all. Octavian had every reason to prevent Cleopatra from becoming a political threat.

As the mother of Caesarion and the former partner of Antony, she embodied potential future resistance or rebellion.

If she had lived, she could have been paraded through Rome in a triumph, which risked stirring public sympathy or undermining Octavian’s claims to legitimate power.

Eliminating her, whether by direct order or quiet coercion, removed a dangerous rival.

What do modern historians think?

Most modern scholars accept that Cleopatra died in 30 BC but approach ancient accounts of her death with caution.

The reliability of Plutarch, Suetonius, and Dio Cassius is limited by the time that had passed, their use of earlier sources, and their closeness to Roman imperial power.

These writers often repeated convenient narratives that suited the political aims of Augustus and his supporters, who wished to portray the victory over Egypt as a triumph of Roman discipline over foreign decadence.

Historians who favour the poison theory cite the inconsistencies in the snake story and the practical challenges it presents.

Poison could be prepared quietly and taken without ceremony, while Cleopatra had time, resources, and the knowledge to arrange her death carefully.

The simultaneous deaths of her two attendants, if true, also support the idea that a shared poison was used, rather than a single reptile.

Some modern researchers have also explored the political messaging behind her death.

When Octavian presented her suicide as voluntary and noble, he removed any suspicion of cruelty and strengthened the belief that his victory had restored Roman virtue.

Cleopatra’s death, therefore, became part of a myth that supported the transition from Republic to Principate.

Her body was never recovered, and no physical evidence survives to support any specific cause, which leaves historians to consider likelihoods rather than certainties.

No modern scholar accepts the old romantic belief that Cleopatra chose death purely for love.

She had demonstrated political cunning throughout her reign and consistently prioritised the survival of her kingdom and her children.

Her decision, whatever the method, likely arose from the collapse of her final options and her understanding of what awaited her under Roman control.

The problem of Octavian (who became Augustus)

Octavian emerged from the crisis as the dominant power in the Mediterranean world.

With Antony and Cleopatra gone and Egypt a Roman province, he controlled both the eastern and western parts of the empire.

Also, his adoption by Julius Caesar gave him a dynastic claim, and his military success secured the loyalty of the legions.

In 27 BC, the Senate granted him the title Augustus, which formally ended the Republic and began the Roman Empire.

Cleopatra’s survival would have posed several dangers to his authority. Her presence in Roman politics, whether in captivity or exile, would have provided a rallying point for opponents of Octavian’s rise.

By eliminating her and Caesarion, Octavian removed all rivals with direct links to Caesar’s bloodline and consolidated his claim to supreme authority.

According to ancient sources, Caesarion was captured and executed on Octavian’s orders, who allegedly declared that "Too many Caesars is not a good thing."

Utlimately, Roman propaganda recast Cleopatra’s memory with poets such as Horace and Virgil described her as a dangerous seductress, while historians portrayed her as a foreign queen who had led Antony astray.

These stories helped position Augustus as a defender of Roman values against outside corruption.

As a result, her death became a useful ending to a narrative in which Rome triumphed over excessive luxury that had undermined Roman values.

The truth behind her final moments was less important than the message it served.

The silence of reliable witnesses, combined with the political interests of those who told the story, ensured that Cleopatra’s death would remain one of history’s most persistent mysteries.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.