De Re Coquinaria: the oldest surviving Ancient Roman cookbook

The De Re Coquinaria, or On the Subject of Cooking, is the most comprehensive Roman cookbook and provides remarkable understanding of upper-class cooking culture during the imperial period.

Although earlier Roman texts such as Cato the Elder's De Agricultura included individual recipes, De Re Coquinaria is the oldest full-length collection devoted entirely to cookery.

Who wrote De Re Coquinaria?

The surviving manuscript of De Re Coquinaria dates from the late 4th or early 5th century CE, though the contents themselves likely originated earlier, as they drew upon culinary traditions from the 1st century CE and possibly even before.

Scholars have attributed the work to a figure named Apicius, yet no firm evidence links the entire compilation to a single author.

The name probably refers to Marcus Gavius Apicius, a wealthy Roman renowned for his extravagant feasts and obsession with luxury dining during the reign of Tiberius.

However, there were several individuals named Apicius throughout Roman history, but ancient sources such as Seneca and Pliny the Elder mentioned him with disapproval, using his name as a symbol of excess and culinary decadence.

According to later tradition, he squandered a vast fortune, reportedly 100 million sestertii, on food and took his own life when he feared he could no longer sustain his lavish lifestyle.

The text includes over 400 recipes, organised into ten sections that roughly follow topic groups such as hors d’oeuvres, sauces, meats, fish, vegetables, and sweet dishes.

These divisions do not always follow consistent categories, and some overlap occurs across the books.

Its Latin displays considerable variation in vocabulary with fluctuating spelling and shifting syntax, which suggests the presence of multiple authors or the gradual development of the collection through repeated edits and additions by later copyists.

Rather than offering exact instructions, most recipes simply list ingredients and then outline general cooking processes in brief phrases.

One such recipe for pork stew instructs the cook to combine liquamen (a fermented fish sauce), wine, honey and vinegar.

It includes the vague directive to “cook it until done,” which indicates that the intended audience consisted of experienced cooks who already knew how to adapt recipes to taste and context.

Scholars have argued whether liquamen and garum were separate sauces or different names for the same fermented fish product, possibly differing in quality or origin.

The Roman recipes and ingredients it contains

The ingredients described throughout the book reveal a great deal about Roman trade networks, agricultural practices, and elite dietary expectations.

Recipes frequently include imported spices such as pepper, asafoetida, ginger, and cinnamon, which reached Rome through land and sea routes from Asia and the Near East.

Some dishes call for ingredients that are now unavailable or widely believed to be extinct, such as silphium, or feature extravagant choices like flamingo tongues, sow’s womb, and stuffed dormice.

Dishes often involve distinctive flavour combinations, such as meat cooked with sweet fruit and aromatic herbs or fish prepared with honey, wine, and vinegar.

Staples like olive oil, honey, and vinegar appear repeatedly, as do fermented condiments, which added depth and saltiness to Roman cuisine.

Wealthy households sourced many of these ingredients from across the empire, which meant that they had access to flavours unavailable to ordinary citizens.

Roman domestic kitchens operated as centres of skilled labour, where trained cooks used a variety of specialised tools and techniques to prepare meals for their masters and guests.

Households that could afford the recipes in De Re Coquinaria often employed slaves or freedmen with professional culinary knowledge, and the kitchens themselves contained bronze grills, iron spits, ceramic vessels, and mortars for grinding spices and blending sauces.

Some recipes instruct the cook to thicken sauces with wheat starch or enrich them with wine must, and others require techniques such as slow simmering, searing over coals, or finishing dishes with reductions.

The instructions in the cookbook assume access to this equipment and knowledge of detailed methods.

In contrast, most ordinary Romans sustained themselves on simpler meals based on bread, porridge, beans, and vegetables, and they rarely consumed the kinds of luxury foods described in the book.

Their main evening meal, or cena, typically lacked the elaborate presentations or exotic ingredients found at aristocratic banquets, and many urban dwellers relied on street vendors or the thermopolium for affordable hot food.

How did an ancient Roman cookbook survive?

The preservation of De Re Coquinaria relied on a limited number of medieval manuscripts rather than widespread copying in monasteries.

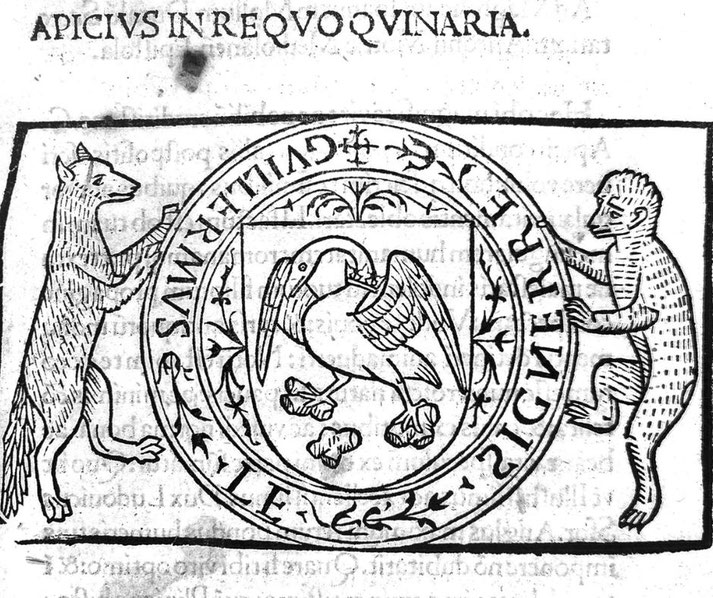

Nonetheless, the text survived long enough to reach Renaissance scholars, and one of the first printed editions appeared in Milan in 1498.

Interest in ancient Roman culture prompted renewed attention to the cookbook, and early modern humanists viewed it as both a linguistic source and a cultural artifact.

Translations into modern languages began to appear in the 19th century, though only in the 20th and 21st centuries did historians begin to study it as a serious source for reconstructing ancient foodways and the everyday practices of elite households.

In recent decades, chefs and scholars have attempted to recreate Roman recipes from the text by modifying proportions, omitting ethically problematic ingredients and substituting unavailable ones so that the dishes became comprehensible and acceptable to modern tastes.

Although it does not reflect the habits of all social classes, De Re Coquinaria is still one of the most important documents for understanding how food served in the Roman world as a indicator of wealth and health.

Thanks to its recipes and instructions, modern readers can explore how a society expressed its tastes through culinary art.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.