The Code of Hammurabi: Law and power in ancient Babylon

During the eighteenth century BCE, King Hammurabi of Babylon introduced probably one of the earliest and most important legal codes known to history.

Hammurabi ruled from approximately 1792 to 1750 BCE during the Old Babylonian period and strengthened Babylon’s control through military conquest and calculated diplomacy, while bringing more power to the palace to bind newly acquired territories to the monarchy.

After he had defeated rival cities such as Larsa and Mari, he had effectively unified southern Mesopotamia and secured his rule.

To manage the populations that were under his control and assert authority over disputes, he had ordered the creation of a unified legal code that would make justice more consistent across his empire.

What was the Code of Hammurabi?

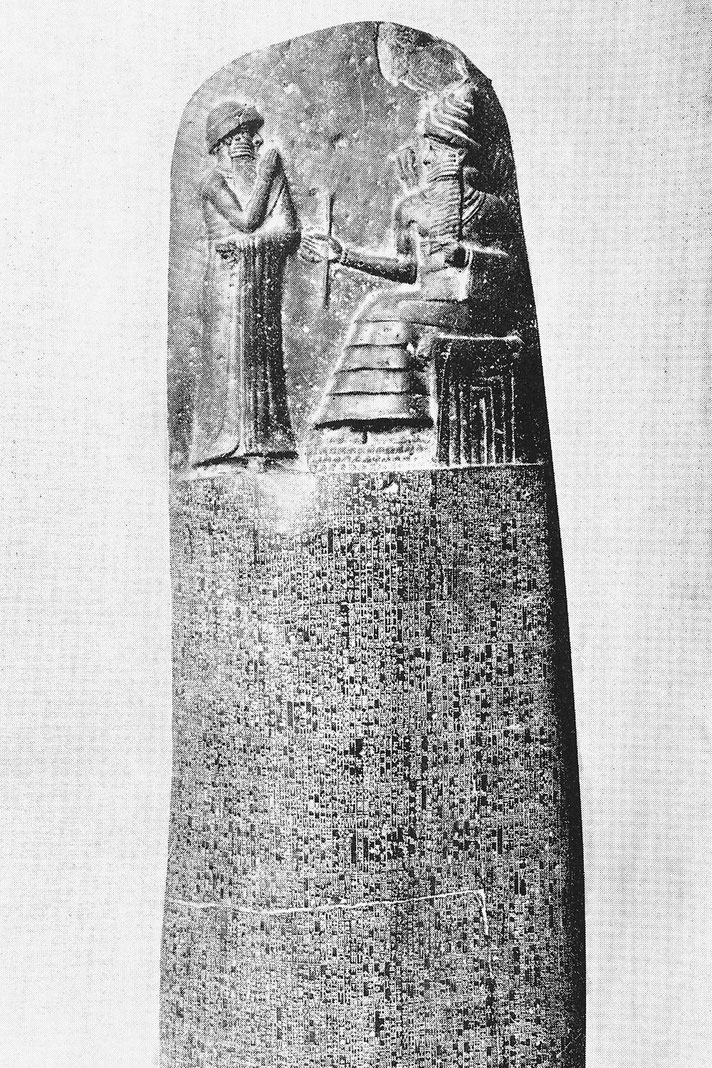

The law code stele of Hammurabi was carved into a single block of black diorite, which was over two metres in height and written in Akkadian cuneiform.

A carving at the top showed the Babylonian king standing before Shamash, the Babylonian god of justice, who hands him a rod and ring as symbols of rulership.

These items were often linked to religious measurement and moral order, and supported the image of Hammurabi as a religious lawgiver.

This divine endorsement placed Hammurabi in a position to administer justice with sacred authority.

Below the image, 282 laws were inscribed in conditional language that began with “If a man...” and ended with set punishments, fines, or solutions.

The laws dealt with practical concerns that affected Babylonian citizens in daily life, as they set rules for buying and selling, work contracts, farming duties, theft, and violent crimes.

For example, law 7 imposed death on those who knowingly received stolen goods under specific circumstances, such as receiving them from a minor or a fugitive slave, while law 42 fined people who let water escape from their property and damage others’ fields, and made them pay for the loss.

In matters that concerned structural safety, law 229 sentenced careless builders to death if a poorly built house collapsed and killed the owner.

By contrast, Law 218 ordered the amputation of a physician’s hand if a surgical operation caused the death of a free man, though fines applied when treating lower-status individuals.

As a result, the law made professional responsibility a formal expectation within the code, especially for skilled trades such as medicine and construction.

Punishments by social class

Legal outcomes depended heavily on the social rank of the people involved. The code divided Babylonian society into three broad categories: the awilu (free person), the mushkenu (dependent), and the wardu (slave).

Penalties shifted according to these classes. For instance, law 196 declared, “If a man destroys the eye of another man, they shall destroy his eye.”

However, if the injured person belonged to a lower class, the punishment often required a fine rather than retribution.

Law 195 punished sons who struck their fathers by cutting off their hands. In this way, the laws put social hierarchy at the centre of legal decisions.

Slaves received the harshest outcomes, yet the code still acknowledged some rights, such as the opportunity to purchase freedom or be freed for service.

Marriage, family, and inheritance laws took up much of the code, since the rules clarified the obligations of spouses, the inheritance rights of children, and the status of concubines and dependents.

For example, law 138 allowed a husband to divorce his wife for negligence or infertility.

To enforce this, the husband had to return her dowry and, if she had borne him children, provide ongoing support.

By contrast, law 129 punished adultery with death by drowning for both participants, though the husband or the king could grant a pardon in certain cases.

Law 148 protected women who became ill after marriage and allowed them to remain in the home and receive support.

As a result, the code treated faithfulness in marriage as essential to the family unit’s legal and moral integrity.

However, women retained some legal protections and, in some cases, could own property or act as priestesses, yet they remained under male control in most areas of life.

Role of religion in Babylonian laws

Religious institutions appeared frequently in the code. They held land, stored wealth, and operated as economic centres, and, as such, the laws safeguarded temple property, outlined the rights and duties of priests, and forbade the misuse of offerings.

To enforce this, law 6 ordered execution for those who stole from a temple.

This is because temples housed records and administered legal contracts, worked closely with the palace, and became key locations for enforcing state power.

As mentioned above, Hammurabi framed himself as the chosen of Shamash and as a shepherd-king who promoted justice.

However, practically speaking, justice relied on official enforcement. Local judges and scribes handled legal cases, recorded transactions, and settled disputes.

Law 5 punished judges who issued false rulings with dismissal and fines, and made judges accountable for their conduct, while witnesses had to verify business dealings, marriage arrangements, and criminal accusations.

Law 2 required that those accused of sorcery or serious crimes undergo an ordeal by river to prove their innocence.

When completed, Hammurabi had placed the stele in a prominent location where it could be seen and read by anyone literate.

Scholars who study its origins suggest it may have stood in a major temple such as that of Marduk in Babylon, and to enforce this the text warned that kings who ignored or altered the laws would be cursed by the gods.

Transmission of the Code

Over time, copies of the laws had appeared in other parts of the empire since scribes may have used them in training exercises or to resolve difficult cases.

However, the laws did not form a uniform legal system in practice because local judges, who also relied on precedent and customary rulings, often made decisions based on local custom.

Regardless, the laws influenced expectations and strengthened royal authority across the region.

Some versions were likely written on clay tablets and stored in temple archives. In the final section, Hammurabi described himself as “the king who caused justice to prevail in the land,” and, ultimately, the laws supported that claim by defining acceptable behaviour and the penalties for disobedience.

Centuries later, Elamite forces had looted Babylon and taken the stele to the city of Susa in modern-day Iran, where it had lain buried until French archaeologist Jacques de Morgan discovered it in 1901.

Today, it sits in the Louvre Museum in Paris, where scholars continue to study its content and its significance, and it still is the most complete legal document from ancient Mesopotamia.

Although earlier law collections existed in Sumer, such as the Code of Ur-Nammu and the laws of Lipit-Ishtar, Hammurabi’s code provided the most detailed and well-preserved legal framework from the region.

Later rulers, including those from the Kassite and Assyrian dynasties, used similar phrasing and format in their own laws.

Lastly, some modern historians argue that the code may have functioned more as royal propaganda than as a reflection of daily legal practice.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.