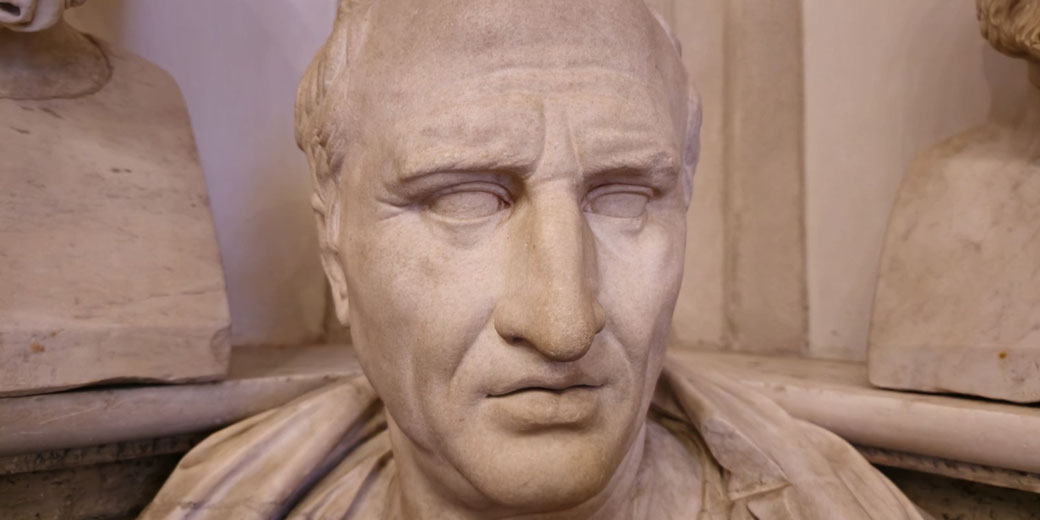

Marcus Tullius Cicero: the Roman who spoke passionately against tyrants and was killed for it

In the final decades of the Roman Republic, the voice of Marcus Tullisu Cicero cut through the chaos of civil unrest and widespread corruption of the age.

He claimed to defend the traditions of the Republic with clear eloquence and called out those who aimed for absolute power.

Yet the very system he fought to preserve abandoned him, and his enemies ensured that the mouth which had once ruled the courts of Rome would speak no more.

Cicero's early life and compulsion to succeed

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born in 106 BCE in Arpinum, a town located southeast of Rome that had only received full Roman citizenship a century earlier.

His family belonged to the equestrian class, and although they held wealth and status, they had no ancestral claim to Rome’s political elite.

Cicero pursued education with determination and learned from Rome’s finest teachers.

He mastered grammar, rhetoric, and philosophy before he travelled to Athens and Rhodes so that he could study under some of the most respected minds of the Greek-speaking world.

He listened to Posidonius, the Stoic philosopher, and learned oratory from Apollonius Molon, who had previously trained Julius Caesar.

He combined Greek rhetorical principles with Roman values, refining a style that relied on logical structure with moral clarity and purposeful argument.

When he returned to Rome, Cicero launched his legal career with a striking action.

In 80 BCE, he defended Sextus Roscius, a man accused of parricide, by directly challenging Chrysogonus, a freedman acting under the authority of Sulla.

This brought Cicero early fame and marked him as a courageous defender of justice.

Cicero understood the risks of such a case, but he believed that silence in the face of injustice would destroy the credibility he needed to enter Roman public life.

He used the case against Sulla's faction to show his legal skill, his command of Roman law, and his commitment to traditional Republican ideals.

After the trial, Cicero withdrew temporarily to Greece to improve his health and to polish his oratory, but his desire to return as a public figure never wavered.

Remarkable success in the cut-throat political life of Rome

By 75 BCE, Cicero had secured the office of quaestor in western Sicily, where his honesty and skill won the local support.

He returned to Rome with strong support and launched a case against Gaius Verres, the corrupt former governor of Sicily.

In 70 BCE, Cicero defeated Verres in a series of carefully prepared speeches that relied on documented abuse, detailed financial evidence, and the testimonies of Sicilian witnesses.

Verres chose exile before the trial had finished, and people began to associate Cicero's name with legal power.

He continued his rise with great speed, securing the offices of aedile in 69 BCE and praetor in 66 BCE.

In 63 BCE, he won the highest office of the Republic when he was elected consul.

He reached this position as a novus homo, or “new man,”, which meant he had no consular ancestors.

Few men had ever achieved this without noble heritage. His election relied on widespread respect for his speaking skills and his impartiality in court.

As consul, Cicero faced the Catilinarian Conspiracy, an armed plot to overthrow the Republic led by Lucius Sergius Catilina.

Cicero responded by delivering a series of four speeches to the Senate and the people, describing the plot clearly and driving Catiline out of the city.

After arresting five of Catiline’s supporters, Cicero consulted the Senate and arranged for their execution without trial.

The Senate praised his actions and awarded him the title pater patriae, 'father of the fatherland', but not all Romans agreed that his actions had upheld justice.

Why was Cicero such a powerful public speaker?

Cicero gained his reputation as Rome’s greatest orator because he understood that persuasive speech required a lot more than just sharp language.

He believed that an effective speaker needed to possess integrity, wisdom, and mastery of human emotion.

As a result, he viewed rhetoric as a tool to preserve public order and protect legal rights.

He did not speak only to win cases or elections: he used his words to defend the values he believed held Rome together.

In particular, he combined logic and structure with vivid examples and historical comparisons.

In his defence of Archias in 62 BCE, Cicero argued that literature contributed to civic life, and he used poetry, memory, and legal argument to persuade the court.

In his Pro Milone speech, which defended Titus Annius Milo against the charge of murder, Cicero balanced technical legal defence with emotional appeals about fear, duty, and public safety.

Speeches such as the Philippics showed how he could undermine an opponent's reputation, and he kept his rhetoric balanced and clear.

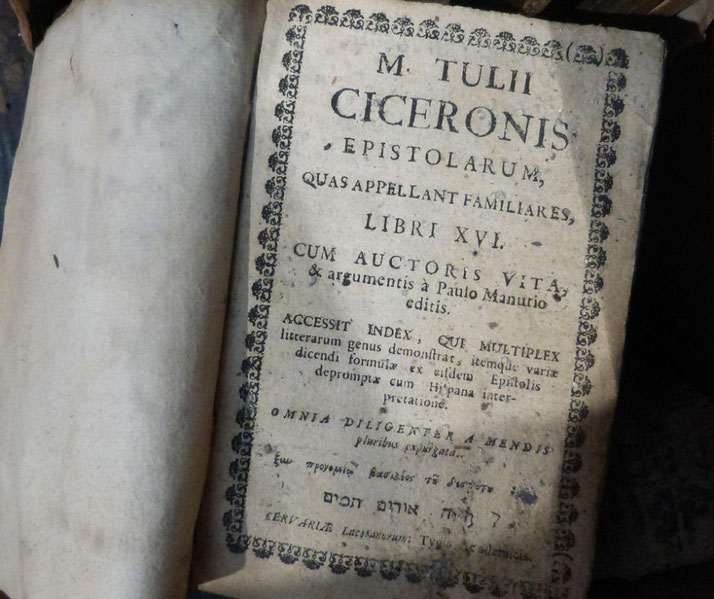

He also wrote extensively on the theory of speaking. In works such as De Oratore and Brutus, Cicero outlined the history of Roman rhetoric and explained how speakers combined elegance and humour with precise delivery.

His fusion of Stoic ethics with rhetorical training set a new standard for civic education in the late Republic.

How Cicero changed from hero to villain

After his consulship, Cicero expected Rome to reward him with continued influence and honour.

Instead, his political enemies began to undermine his position. The executions of the Catilinarian conspirators had violated the rights of Roman citizens, and this provided a legal basis for retaliation.

In 58 BCE, Publius Clodius Pulcher, who had become tribune of the plebs, passed a law that targeted anyone who had executed Roman citizens without trial.

Although the law did not name Cicero, it was clearly designed to remove him.

Because he feared arrest and humiliation, Cicero left Rome and travelled to Macedonia.

In his absence, his enemies destroyed his property, auctioned his possessions, and built a shrine on the site of his home.

His exile lasted just over a year, and he returned in 57 BCE after being recalled by the Senate.

The people greeted him with great enthusiasm, but his position in politics had weakened.

His reliance on Pompey for protection placed him in a difficult position, especially as conflict between Pompey and Caesar began to escalate.

As civil war loomed in 49 BCE, Cicero hoped to avoid taking sides, but pressure forced him to choose.

He declared support for Pompey and the Senate but avoided direct involvement in military affairs.

After Caesar’s victory, Cicero returned to Rome, where Caesar spared him. He withdrew from public life and focused on writing, producing some of his most famous philosophical works, including De Officiis and De Natura Deorum.

His political influence had faded, but he continued to argue that the Republic could still be restored.

Cicero's tragic role in the fall of the Roman republic

When Caesar was assassinated on 15 March 44 BCE, Cicero hoped that the Republic would recover.

He welcomed the conspirators as liberators and urged the Senate to restore constitutional order.

However, events moved quickly. Mark Antony tried to position himself as Caesar’s successor, and Cicero saw him as a tyrant who threatened everything for which he had argued throughout his life.

He delivered a series of speeches called the Philippics, which attacked Antony’s motives, accused him of violence and corruption, and praised Octavian, Caesar’s young heir, as a potential saviour of the Republic.

Cicero believed he could use Octavian to neutralise Antony, and he placed his trust in the boy’s inexperience.

In reality, Octavian had his own ambitions and no interest in preserving Republican traditions.

In 43 BCE, Octavian allied with Antony and Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate.

The three men agreed to eliminate their enemies and issued proscriptions against hundreds of citizens.

Cicero’s name appeared on the list. He tried to flee to Macedonia, but soldiers captured him near his villa at Formiae.

They cut off his head and hands and displayed them in the Forum. Antony’s wife Fulvia reportedly stabbed his tongue with a hairpin to symbolise her hatred for his voice.

Cicero's legacy has influenced western civilization

Although Cicero’s life ended in violence, his writings continued to influence future generations.

His speeches became models for rhetorical education, and his treatises on ethics, duty, and law informed Roman political thought.

Medieval scholars preserved his works, and Renaissance humanists praised his Latin style and civic ideals.

His letters provided historians with a detailed account of the collapse of the Republic and the personalities who shaped it.

In the early modern period, thinkers such as John Locke, David Hume, and Montesquieu cited Cicero’s ideas about natural law, constitutional balance, and individual duty.

His belief that moral responsibility must guide public service appealed to philosophers and revolutionaries alike.

In the United States, the Founding Fathers admired his writings and often quoted him in debates about liberty and law.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.