Rome's addiction to deadly speed: The thrills and spills of ancient chariot racing

In the centre of ancient Rome, under the hot sun, the loud roar of the crowd filled the large Circus Maximus.

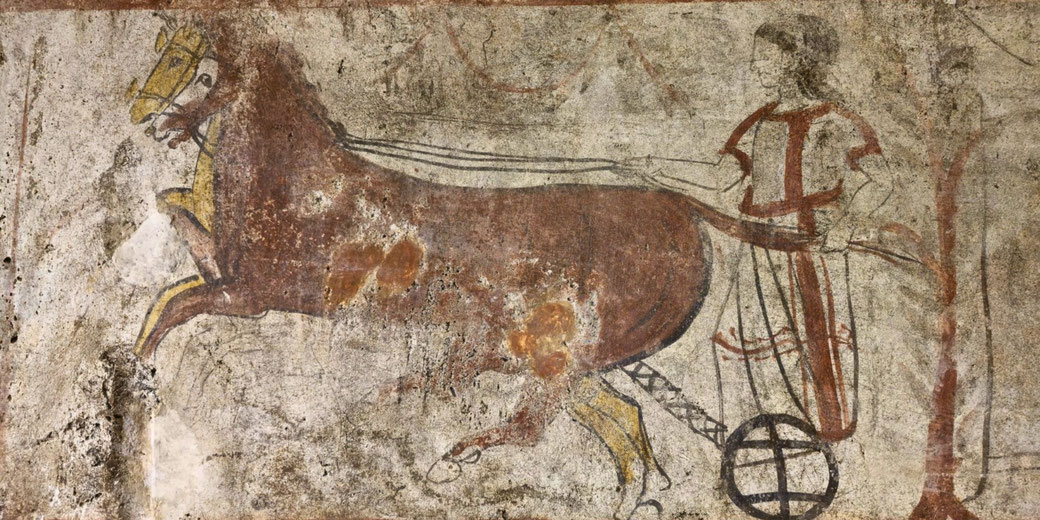

Chariots, which were pulled by horses that foamed at the mouth, raced very close to each other. Their wheels nearly touched as the chariots sped down the track.

Charioteers, who kept their jaws set and held the reins tightly, risked their lives for victory, praise, and loud cheers from the spectators.

What made these men risk everything in this deadly sport?

The origins of chariot racing in Rome

The Etruscans who once ruled much of Italy before Rome’s rise are thought to have introduced chariot racing to the Romans.

Later, the Romans added chariot races to their own festivals and celebrations.

Early races in Rome were closely connected to the worship of gods such as Mars, the god of war, and Consus, the god of grain and harvest.

These ceremonies took place at the base of the Palatine Hill.

Where were chariot races held?

According to tradition, the Circus Maximus was built during the rule of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (r. 616–579 BCE), and it quickly became Rome’s main racing site.

It started as a simple track and later became an impressive structure under various emperors, holding about 250,000 people.

The Circus Maximus measured about 621 metres long and had a U shape, with a spina, the central barrier, down its middle.

The spina held obelisks and statues, features that were thought to add a sense of imperial power to the excitement of the race.

Although the Circus Maximus was the most famous site for the races, Rome had a number of other circuses.

However, they had fewer spectators than the central city venues.

Interestingly, Roman chariot racing later had a strong influence on the eastern empire at the Hippodrome in Constantinople.

The Hippodrome became central to life in the eastern capital, where it combined politics, sport, and public celebrations, similarly to the Circus Maximus.

The most famous chariot racing teams

Initially, there were two main teams you could support. These were called 'factions': the Reds (Russata) and the Whites (Albata).

As the sport's popularity rose, two more factions appeared: the Blues (Veneta) and the Greens (Prasina).

Over time, their supporters showed a steady and often fierce loyalty.

While they started as dedicated sports fans, they quickly moved into politics.

Even the Emperors had to align with one of these leading factions in order to deal with frequent street riots between different groups.

One of the most notorious events was the Nika riots of AD 532 in Constantinople in which the supporters of the Blues and Greens joined in a rebellion against Emperor Justinian and almost ended his reign.

How to become a chariot racer in ancient Rome

Many charioteers were initially as slaves or freedmen (people who had been slaves but had been released).

Becoming a star racer could help them gain significance wealth and become household names.

There is surviving evidence that shows that the best of them accrued large fortunes and even appeared in romantic and heroic stories.

However, these men faced grave risks every time they took to the track, as many races ended in injury or death. Dozens of charioteers died each year.

One famous example was Gaius Appuleius Diocles, who raced for the Reds, Whites and Greens.

His career lasted over twenty years, during which he won a massive fortune and befriended some of Rome's wealthiest people.

An inscription records his total career earnings as 35,863,120 sesterces, with is roughly equal to $15 billion today.

Charioteers like Diocles became a romantisised symbol of hope to the poverty-stricken masses in Rome.

He showed that someone could rise from humble origins to the very top of society, if they were lucky.

What happened during a chariot race?

A typical race had twelve chariots that had to complete seven laps around the spina of the circus.

The most common type of chariot was the quadriga, which called so (‘quad’ means ‘four’) because it was pulled by four horses that galloped side-by-side.

While this provided significant speed, this meant that the charioteer had to manage to control the four horses.

Such situations required careful balance: both pushing for speed while keeping the horses working together using both a whip and shouted commands.

However, it was the turns at each end of the spina were the most dangerous parts of the race.

These were referred to as the metae (turning posts) and it is here that chariots often crashed into each other or the barrier wall.

Sadly, such crashes could be the most dramatic and the deadliest part of the event.

As a result, strategy became important. Charioteers had to decide whether to choose the riskier inner track, which was shorter but carried a higher chance of collisions, or the outer, longer, but safer route.

That being said, the danger added to the appeal of the race for the spectators. At those moments, the audience held their breath as chariots navigated these turns, and would often re-live each second of that moment in discussions afterwards, as they walked home from the circus.

For the charioteers, in the heat of the moment, there was a strong mental contest at play.

They had to try and read their competitors, anticipate moves and adjust their own strategies on the fly.

Before an event, some of them formed temporary alliances to team up against a particularly powerful charioteer before competing fiercely against each other in the final laps.

Others might employ deceptive tactics, feigning weakness only to unleash a burst of speed at the last moment.

However, there could only ever be one winner. The charioteer that crossed the line first would be praised as a hero and awarded a palm branch and a wreath of laurel, along with any prize money that had been on offer.

However, for some it was the glory, the praise of the crowd, and the chance to be immortalised in song and story that was the most valuable prize.

How the rich and poor were treated differently

But what was it like to be in the crowd of these events? Sadly, the very nature of the Circus Maximus, with its tiered seating, reinforced the rigid social divisions of Rome.

Senators and elite aristocrats usually occupied the best seats close to the track, with comfortable cushions and shaded covers. Meanwhile, the general populace filled the upper tiers.

The further away from the track you were, the worse viewing angle you had and the poorer you were.

Nevertheless, for all these divisions, the circus was one of the few places where the entire spectrum of Roman society, from the emperor to the commoner, gathered together.

This rare moment of somewhat societal unity often acted as a pressure valve. It gave the masses a temporary respite from the challenges of their daily lives.

Emperors clearly recognised the importance of 'bread and circuses' (panem et circenses) as a means to placate and control the populace, and, as such, invested heavily in the games.

They sponsored grand races to ensure that the populace was entertained, which was a tried-and-true way to divert attention from pressing political issues, economic downturns, or recent military disasters.

However, this strategy was a double-edged sword. While successful games could boost an emperor's popularity, any perceived mismanagement could incite the crowd's anger and become a potential site for political dissent.

The different colour factions further complicated this risk. In particular, as the Blues and the Greens became embroiled with political intrigues, different emperors and senators would use them against certain factions based on the changing nature of Roman politics.

Why chariot racing fell from popularity

Economically, chariot races became unsustainable, as the costs of organising them and repairing the circuses and stadia mounted every year.

As the western Roman Empire struggled with economic problems, invasions, and internal conflicts in the third century, funding for chariot racing began to decline.

Also, early Christian leaders saw the games as pagan shows full of excess and began to oppose them.

Subsequently, emperors, once the main supporters of chariot racing, especially after Constantine's turn to Christianity, sometimes openly against the games.

Later, Theodosius I, in the late fourth century AD, banned many pagan festivals and games.

However, chariot racing survived in the Eastern Roman Empire where the Hippodrome of Constantinople continued to hold chariot races long after they had disappeared in the west.

Finally, the sport’s popularity slowly declined and by the end of the first millennium AD, it had practically disappeared as an important social event.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.