The tragically short life of Caesarion, the only child of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra

In 47 BCE, a child was born who would live through both the height and the collapse of two ancient civilisations. He was named Ptolemy XV Caesar and nicknamed Caesarion, and people widely believed that he likely carried the blood of Julius Caesar and Cleopatra VII.

Those two rulers had shaken the foundations of the Mediterranean world. From the moment of his birth, Roman statesmen increasingly viewed him as a threat, while Egyptian priests elevated him as a divine heir.

Being a young pawn in the greatest struggle of the age

At the time of Caesarion’s birth, Cleopatra had regained the throne of Egypt with Julius Caesar’s support following the Alexandrian War.

She named her son in his honour and declared publicly that Caesar was the father.

By doing so, she strengthened her position in Egypt and asserted family ties with the most powerful man in the Roman world.

Julius Caesar, however, did not formally acknowledge Caesarion under Roman law, yet he allowed Cleopatra and her son to stay in his villa across the Tiber during their visit to Rome.

Since Roman law forbade citizens from marrying foreign monarchs, Caesar’s lack of legal recognition for Caesarion left his status unclear.

This arrangement, which was widely known among Rome’s political class, added considerable weight to Cleopatra’s claim and caused concern in the Senate, as Roman observers feared that Caesar's behaviour pointed toward monarchy and thought he might use Caesarion to establish a hereditary rule.

Although his will had named Octavian as his sole legal heir, it had made no mention of Caesarion.

Soon after Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, Cleopatra returned to Egypt with her son and, at that point, formally declared Caesarion co-ruler under the dynastic name Ptolemy XV.

Although he was only three years old, his image began to appear regularly alongside hers on official documents, public inscriptions, and religious monuments.

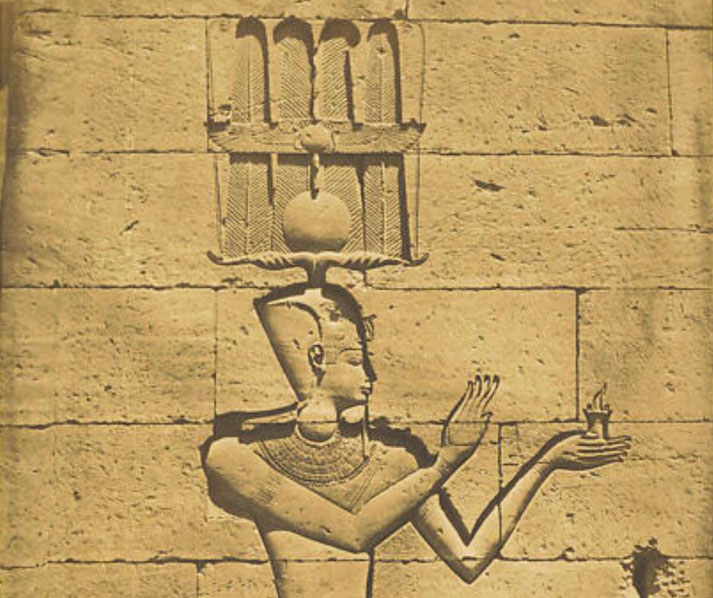

As part of a careful plan, Cleopatra promoted him as both pharaoh and son of a Roman declared a god.

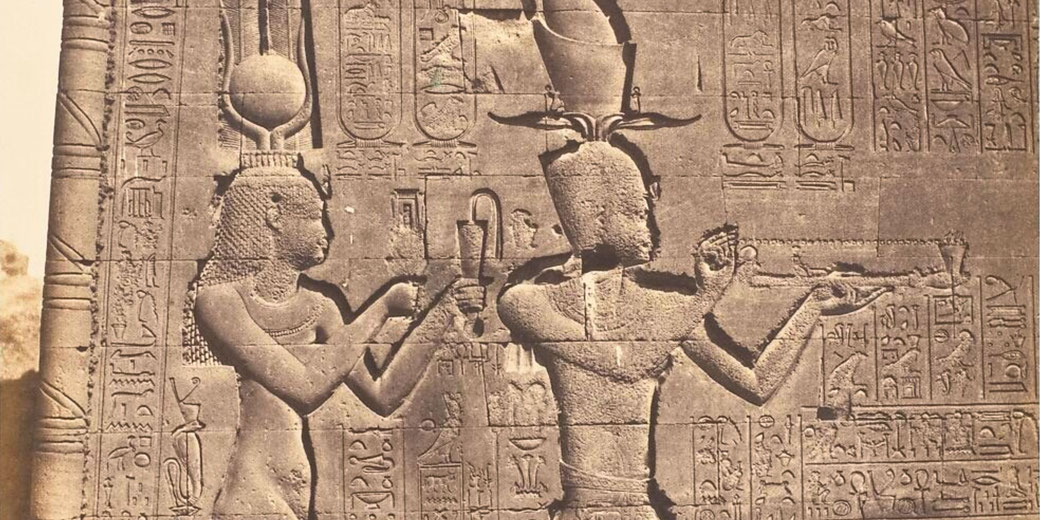

Temple carvings at Dendera showed him as one who made offerings to the gods, and some claims from Hermonthis (which still remain debated) but nevertheless helped support his sacred image.

As a result, Caesarion became largely a political tool within Cleopatra’s efforts to maintain Egypt’s independence.

She raised him to be seen as a rightful heir to both Egyptian and Roman traditions, and she used temple rituals and royal processions to gradually familiarise the population with his status.

She drew on Ptolemaic religious images and styled herself as Isis and Caesarion as Horus.

Even though his rule remained symbolic, it gradually became central to Egypt’s foreign diplomacy and public messaging.

Why was young Caesarion seen as such threat?

After Caesar’s death, his former allies and enemies split into opposing groups. Two men rose to power during this crisis: Octavian, who was named as Caesar’s adopted son, and Mark Antony, who was a senior military commander and statesman.

By 34 BCE, Mark Antony had formed a personal and military alliance with Cleopatra, and together they effectively used Caesarion to challenge Octavian’s authority.

During the Donations of Alexandria, held in the gymnasium of the city, Antony publicly presented Caesarion as Julius Caesar’s son and rightful heir, though this claim remained politically sensitive and unproven.

He then granted him rule over Egypt, Cyprus, and other eastern territories, while also declaring him “King of Kings.”

Cleopatra received new titles as “Queen of Kings”. A public show followed Antony’s campaign in Armenia and posed a serious challenge to Roman traditions, where only the Senate could assign provinces.

At once, this announcement transformed Caesarion from a regional prince into a direct threat to Rome’s political future.

Octavian used the Donations to create considerable public anger, as he accused Antony of weakening Roman values and betraying the Republic to a foreign queen.

Ultimately, he emphasised that Antony’s recognition of Caesarion violated the authority of Caesar’s will, which had adopted Octavian as his only legal heir.

For Octavian’s cause, Caesarion’s existence became a dangerous liability. He showed the idea that Caesar had a true son who might claim both Egypt and Rome.

Roman senators, poets, and writers began publicly attacking the boy’s right to rule, portraying him as a child who was born of seduction and manipulation, who was raised outside Roman traditions and who was destined to undermine its laws.

Octavian’s campaign of public messaging had widely used publications in the Acta Diurna and pro-Augustan literature such as poems by Virgil and Horace, which celebrated Octavian’s right to rule and which portrayed Egypt as a harmful influence.

The Res Gestae Divi Augusti, written years later, even omitted Caesarion altogether.

Eventually, the issue of Caesarion’s status helped Octavian win support for war, because his campaign against Antony and Cleopatra largely focused less on Antony’s personal betrayal and more on the threat that Caesarion’s future rule posed to Rome's control.

Caesarion's brief reign as pharaoh of Egypt

While Cleopatra controlled the affairs of state, Caesarion was gradually introduced to the duties of Egyptian kingship.

From 44 BCE onward, his name had begun regularly appearing on public inscriptions and religious dedications.

Priests in Upper Egypt had made carvings that notably showed him as one who made offerings to the gods and that depicted him dressed in the pharaoh's royal dress.

By placing Caesarion at the centre of public rituals, Cleopatra asserted that her son had inherited sacred favour, as he was referred to as “Son of the god Caesar,” and his image reinforced the claim that Egypt’s monarchy could continue through Roman ties.

On coins issued in Alexandria, Cleopatra paired her face with his and presented a unified royal authority based on lineage and religious claim.

As Caesarion grew older, his official role in court increased, and Cleopatra included him in state receptions, religious festivals, and meetings with foreign representatives.

These activities gave him no real power and nevertheless shaped public perception of him as the next ruler of Egypt.

Nevertheless, his status depended entirely on Cleopatra’s authority. He had no political independence, commanded no troops, and made no decisions regarding administration or foreign policy.

His brief reign was the final extension of the Ptolemaic tradition, and his role was to preserve continuity rather than to create change.

The final conquest of Egypt by Rome

By the end of 32 BCE, tensions between Octavian and Antony escalated into war and, on 2 September 31 BCE, the opposing fleets met at the Battle of Actium.

Octavian’s navy, commanded by Agrippa, forced Antony and Cleopatra to retreat.

Afterwards, they fled to Egypt and attempted to rebuild their position, but Roman forces advanced rapidly towards Alexandria.

As Octavian closed in, Cleopatra placed Caesarion at the centre of her final diplomatic efforts.

She sent messages offering to surrender her throne if her son could be spared.

Ancient accounts suggest that she also prepared Caesarion’s escape and may have sent him eastwards, either towards India or the court of a friendly Arabian king.

Some later sources alternatively claimed that he was sent south towards Berenice on the Red Sea coast.

Either direction provided established trade networks that linked Egypt to the east.

Meanwhile, Octavian entered Alexandria in August of 30 BCE where Antony committed suicide after hearing a false report of Cleopatra’s death.

Cleopatra herself was soon cornered and, realised that negotiations had failed, ended her own life shortly after.

At that moment, Caesarion was no longer a prince-in-waiting and became the final element of resistance to Roman rule.

What happened to Caesarion?

According to Roman sources, Caesarion was reportedly intercepted on the road south, either by Octavian’s agents or by Egyptian officials who acted under Roman pressure, and, once captured, he was returned to Alexandria and held in custody.

Advisors close to Octavian privately debated his fate, as some warned against executing the boy, suggesting that it would turn away Egyptian elites or dishonour Caesar’s memory.

Even so, the political risk remained too high, since Caesarion had borne the name of Caesar and had enjoyed the favour of the Egyptian priesthood: circumstances that could make him a rallying figure for unrest in the eastern provinces.

Many ancient writers suggest that Caesarion had been executed on Octavian’s command, although they do not confirm the exact method used in late August 30 BCE, when he was seventeen years old.

After Caesarion’s death, Octavian had formally made Egypt part of Rome and declared it a Roman province.

He placed it under the direct control of a Roman governor and forbade senators from entering the province without permission.

Cornelius Gallus, who was a trusted colleague of Octavian, became Egypt’s first Roman governor.

That meant that the Ptolemaic dynasty had ruled Egypt since the time of Alexander the Great now ended with the death of Cleopatra’s son.

Caesarion left behind no known burial site, though a few reliefs and coins that bear his image still survive.

His image largely disappeared from official records, removed by a government that feared what he represented.

This erasure resembled a form of damnatio memoriae, used to eliminate a rival’s presence from public memory.

Ultimately, through his birth, he had united two of the most powerful empires of the ancient world for a time but, through his death, Rome ensured that no such union would threaten its authority again.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.