The strange occurrences when Julius Caesar and Augustus visited the tomb of Alexander

In two separate moments of crisis and conquest, Julius Caesar and Augustus visited the tomb of Alexander the Great in Alexandria.

The example of the Macedonian king deeply influenced both Roman leaders, and they looked for a physical connection to his memory during their rise to supreme power.

Why was Alexander the Great buried in Alexandria?

After his sudden death in Babylon in 323 BC, Alexander's body became the focus of keen political interest among his former generals.

Macedonian tradition generally required that deceased kings be interred in the royal cemetery at Aegae, where their ancestors had rested for generations.

His own wishes, however, if ever clearly stated, largely became secondary to the aims of those who hoped to benefit from possession of his remains.

While the funeral procession carried his body westward across Mesopotamia and Syria, Ptolemy I, who had secured control of Egypt, reportedly stopped the procession and sent it to Egypt in 322 BC, and he brought it first to Memphis before it was eventually moved to Alexandria.

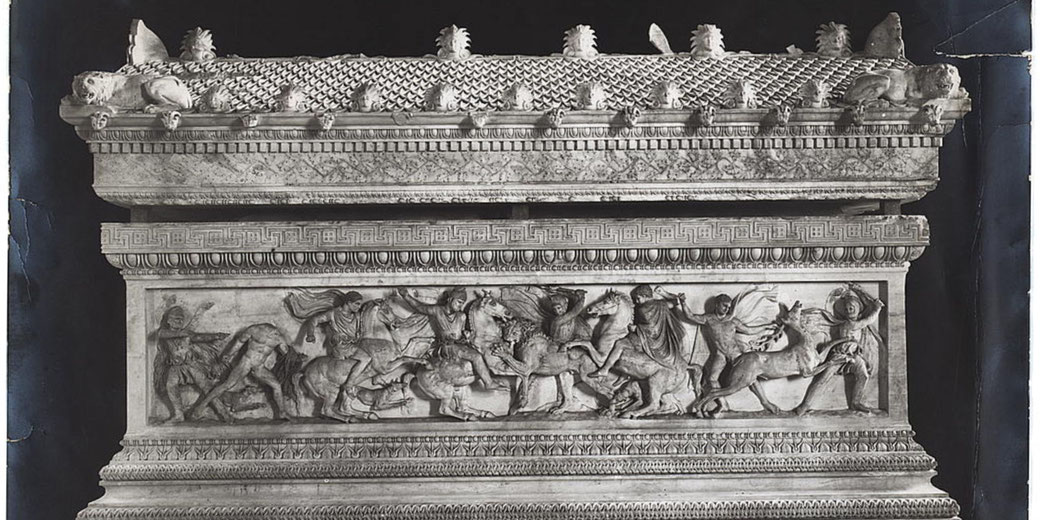

Diodorus Siculus described the funeral cart itself as a massive golden chariot which was constructed in the form of a temple, complete with detailed decorations.

When Ptolemy relocated Alexander's body, he largely ensured that his rule would draw legitimacy from the founder of the city, whom the Egyptian Greeks had already treated as a god.

Alexander himself had laid out Alexandria in 331 BC, but he had never lived to see it completed, and the city quickly transformed into both a cultural centre and a dynastic stage upon which his memory would be preserved.

People had originally called the tomb the Soma, which had begun as a large shrine, but later Ptolemy IV or one of his successors relocated it to a more prominent part of the city.

Surviving accounts described a structure whose Greek architecture included ceremonial spaces alongside rich ornamentation that expressed Hellenistic respect for the dead.

Within its chambers, Alexander's body had lain in a decorated sarcophagus which was possibly made of gold, though ancient sources had not confirmed this, and which later reports had suggested may have been replaced with clear materials such as glass or alabaster to allow public viewing.

Ancient writers such as Strabo and Pausanias had described its location and design in general terms, though their accounts had lacked the detail necessary for precise archaeological identification.

Over time, the tomb had gradually evolved into a place many people visited, where rulers, philosophers, and generals aimed to honour Alexander and to attach themselves to his reputation.

Julius Caesar’s Visit (48 BC)

During the height of the Roman Civil War in 48 BC, Julius Caesar pursued his rival Pompey into Egypt, where he arrived shortly after Pompey's assassination at the hands of Ptolemy XIII's court.

Although Caesar had not intended to linger in Alexandria, the political chaos of the Ptolemaic succession crisis quickly drew him into a prolonged confrontation between Cleopatra VII and her brother.

Amidst these events, Caesar took the opportunity to visit the tomb of Alexander the Great, a man whose reputation had loomed large over Roman imaginations for generations.

According to Plutarch, Caesar had long viewed Alexander as a standard by which military glory should be measured.

When he saw the embalmed body of the Macedonian conqueror, Caesar reportedly wept.

He was said to have said that Alexander had achieved so much by the age of thirty-two, and that he had achieved less despite his high command in Rome.

Within the tomb, Caesar made offerings and showed public respect, likely as a means of displaying both piety and connection to a heroic past.

Augustus’ Visit (30 BC)

After his victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC, Octavian entered Alexandria as the master of the Roman world.

Following the suicides of Mark Antony and Cleopatra in the next year, he rapidly secured Roman control over Egypt and brought the Ptolemaic dynasty to an end.

As part of his planned efforts to present himself as a successor to legitimate rulers, Octavian, soon to become Augustus, demanded access to Alexander's tomb, which still stood intact within the city.

Suetonius and Dio Cassius both recorded the occasion. Augustus entered the tomb with a group of attendants and placed offerings before the body.

He put a golden wreath on the corpse to show respect and to connect himself with the ancient conqueror.

He also reportedly repeated Caesar’s earlier dismissal of the Ptolemies, stating that he had come to see a king and dismissed the mummified body, which he described as belonging to a failed dynasty.

Instead of acknowledging Cleopatra’s lineage, he identified himself with Alexander’s vision of empire.

Later images on coins and statues reinforced this comparison with the Macedonian conqueror.

During the ceremony, Augustus leaned in to view the body more closely. At some point during the visit, he accidentally damaged the remains, either by knocking the sarcophagus or by brushing against the body.

Apparently, Augustus accidentally broke off part of Alexander's nose when he examined the body, the incident disturbed those present.

Public reaction in Alexandria remained largely cautious, though the symbolism of Roman interference in the physical heritage of Alexander became difficult to ignore.

Some later emperors continued the pattern of visiting the tomb. Caligula reportedly removed Alexander’s breastplate for display, which people in Alexandria saw as disrespectful.

Septimius Severus ordered the tomb closed to the public, possibly to prevent further damage, while Caracalla, who was obsessed with Alexander, staged formal ceremonies at the site and declared himself a spiritual successor.

By then, the tomb had already begun to lose much of its importance, and records of its location became increasingly vague.

What happened to Alexander's tomb?

By the late Roman period, the tomb of Alexander had become forgotten, since earthquakes had damaged many of Alexandria's older buildings, and religious changes during the rise of Christianity had led to the closure or destruction of pagan shrines, the site likely fell into disuse or was taken down.

No clear record survived beyond the third century AD.

Later writers suggested possible locations for the tomb. Some believed it lay beneath what became the Nabi Daniel Mosque, while others proposed that it had been moved or hidden during civil unrest.

Archaeological efforts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries uncovered fragments of Greco-Roman buildings beneath modern Alexandria.

However, none could be confidently identified as the tomb. In the 1990s, Greek archaeologist Liana Souvaltzi claimed to have found the tomb in the Siwa Oasis, but Egyptian officials and scholars rejected that claim.

By then, centuries of rebuilding and urban growth had erased the original layout of the royal quarter.

Descriptions by Strabo and Pausanias, which were helpful in general terms, lacked the detail needed for accurate excavation.

For example, Strabo described the tomb as being near the city’s main colonnaded street, but that district had been rebuilt multiple times under Roman and later rule.

As interest in Alexander's memory had continued, the fate of his body had gradually taken on a legendary status.

The visits of Caesar and Augustus had been the last reliable accounts of the body's condition, and each man arrived at the tomb and looked for some affirmation of his own greatness.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.