The Cadaver Synod: when the Catholic Church dug up a dead pope to put his corpse on trial

The complicated politics of the early Middle Ages frequently blurred the line between the sacred and the gruesome.

When the Church became both judge and political player, even the grave offered no refuge. In a chilling demonstration of spiritual authority turned dramatic, a pope’s corpse was dragged from its tomb to stand accused in a courtroom crowded with ambitious actors and fearful observers.

The spectacle provoked fierce outrage.

What was the 'Cadaver Synod'?

In January AD 897, the Catholic Church held one of the most strange and disturbing events in its long history.

Known as the Cadaver Synod or Synodus Horrenda, it was a posthumous ecclesiastical trial held in Rome by Pope Stephen VI against his predecessor, Pope Formosus.

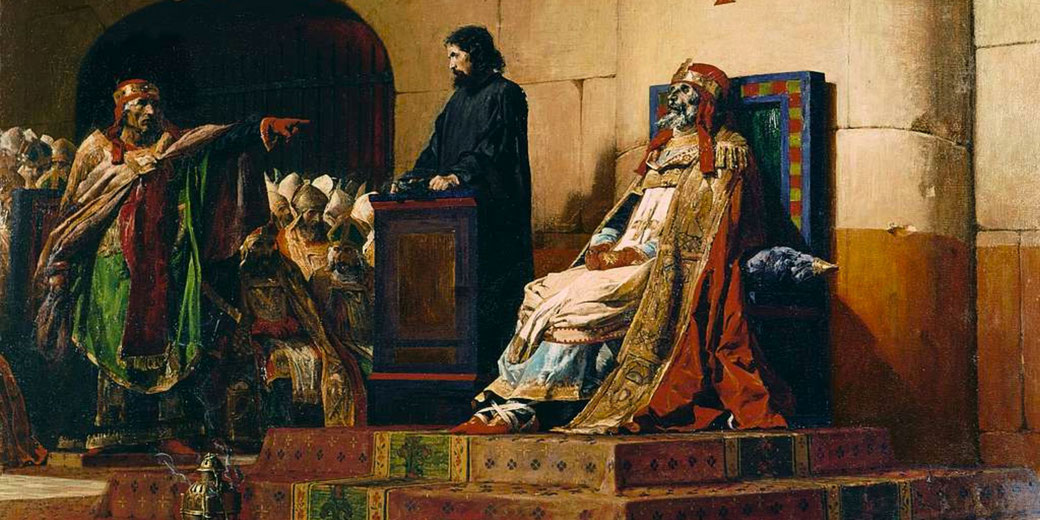

This grim spectacle took place inside the Lateran Basilica, the official cathedral of the bishop of Rome, and involved the digging up of Formosus’ body, which had been buried for about nine months.

The corpse was then dressed in papal vestments and seated on a throne to face formal charges.

The synod was both an act of official condemnation and a clear political statement.

At the time, the papacy was caught in a violent power struggle between noble Roman families and rival factions within the Church.

Formosus had been a controversial figure, having been involved in both secular and ecclesiastical disputes, and his decisions as pope had earned him powerful enemies.

The Cadaver Synod showed how unstable and divided papal politics were in late ninth-century Italy, a period when the office of the pope was often controlled by force and fear rather than by theological leadership.

Why did Stephen want revenge?

Pope Stephen VI had a personal and political motive to humiliate Formosus, even after death.

Before becoming pope, Formosus had clashed with various Roman nobles and had also angered supporters of the powerful Spoletan dynasty.

He had invited Arnulf of Carinthia, a Frankish king, to invade Italy and remove the Spoletan ruler Lambert from power.

Formosus had then crowned Arnulf as Holy Roman Emperor, which weakened Lambert’s authority.

Stephen VI was closely tied to Lambert and the Spoletans and, after their return to power following Arnulf’s defeat and illness, Stephen became pope with their backing.

Stephen’s decision to prosecute Formosus' corpse was a carefully planned move to discredit all of his rival’s actions as pope.

By canceling Formosus’ term as pope, Stephen aimed to undo his predecessor’s appointments, especially those that threatened his allies or his own legitimacy.

At the heart of this was a desire to remove the political gains Formosus had won and to weaken any remaining opposition to the Spoletan faction within the church leadership.

The macabre trial of the corpse

The trial itself was conducted with full ceremony, despite its disturbing nature.

Formosus’ decaying corpse, dressed in the official robes of a pope, was propped up on a throne inside the Lateran Basilica.

A deacon stood beside the body and answered questions on its behalf, speaking for the deceased.

The list of accusations included lying under oath, breaking church law by transferring bishoprics, and unlawfully serving as pope.

These charges were used to attack Formosus for political reasons rather than to clarify legal matters.

The outcome was already decided. The corpse was found guilty, and the synod declared that all of Formosus’ acts as pope were null and void.

His papacy was erased afterwards. His ordinations were declared invalid, removing the authority of the priests and bishops he had consecrated.

This decision sent shockwaves through the Church, since many active clergy owed their position to Formosus.

The trial not only disrespected a dead pope but also threw the authority of recent Church leadership into doubt.

What happened to the body of the former pope?

After the trial, Pope Stephen VI ordered that Formosus’ corpse be stripped of its vestments and treated like a common criminal.

Three fingers of his right hand, which had been used for blessings and church rites, were cut off to show the rejection of his spiritual authority.

His body was first buried in a graveyard for foreigners, chosen to heighten his disgrace. However, this punishment did not end there.

Soon after the initial burial, Stephen ordered that Formosus’ body be dug up again and thrown into the Tiber River.

This was meant to prevent any possibility of burial in holy ground. According to later accounts, some monks or sympathetic clergy retrieved the corpse from the river and reburied it in secret.

The treatment of the body became an example of how far Church politics could go when power took priority over religious tradition and basic human decency.

How did the church respond?

The event caused public anger and widespread unease. Many in Rome saw the trial as a shocking breach of both Christian teaching and common decency.

The idea of putting a corpse on trial, cutting parts of its body off, and throwing it into a river deeply disturbed the Roman clergy and laity.

The uproar led to riots in Rome, and Pope Stephen VI, the man responsible for the synod, was soon imprisoned.

He was strangled to death in his cell later that year, most likely because of public anger and political revenge.

In the aftermath, the Church tried to distance itself from the incident. Successive popes overturned the rulings of the Cadaver Synod, reinstated the acts of Formosus, and restored his honour.

Pope Theodore II had Formosus’ body recovered from the Tiber and reburied with dignity in St Peter’s Basilica.

Later, Pope John IX held two synods in AD 898 that condemned the Cadaver Synod, banned future trials of the dead, and declared Stephen’s actions invalid.

The Church never again attempted such an event, and the Cadaver Synod remains one of the most infamous episodes in papal history.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.