The Battle of Leuctra: The dramatic day when Sparta was brutally crushed on the battlefield

One of the most famous moments in ancient Greek history happened on the day when the mighty Spartan army collapsed in open battle.

On the fields near the Boeotian village of Leuctra in 371 BC, the widely held, unbeatable reputation of Spartan hoplites fell apart in a single, shattering defeat.

The severe defeat inflicted by the Thebans largely broke the myth of Spartan superiority, shifted the centre of power in Greece and showed the weaknesses beneath Sparta’s strict discipline.

How Sparta rose to power in Greece

Sparta's geographical location shielded it from frequent invasion, as it was surrounded by mountain ranges and far removed from the political struggles of other city-states.

As a reuslt, the city developed its systems with little outside interference. Over time, it built a strict social order that focused on military service and civic control.

At the top stood the Spartiates who were full citizens and who trained as warriors, while below them were the perioikoi who handled trade and industry, and the helots who worked the land under severe conditions.

When Sparta secured control over Messenia, it ensured a steady supply of agricultural labour largely because the helots were forced into lifelong servitude and allowed the Spartiates to focus entirely on training and warfare.

From age seven, Spartan boys entered the agoge, a harsh regime that prepared them for life as hoplites, since they learned to endure hardship and to practise weapons and tactics until discipline became part of their routine.

After years of training, this system generally produced the most feared infantry in Greece.

As a result, Sparta earned a fearsome reputation during the Persian Wars because a Spartan-led army had helped repel the Persian invasion at Plataea in 479 BC.

That victory had confirmed Sparta’s military authority, and over the following decades, it expanded its control through the Peloponnesian League.

This alliance of southern city-states relied on Spartan leadership in wartime and helped keep Sparta as the leading power.

Then, during the Peloponnesian War, which broke out in 431 BC, Sparta presented itself as the defender of traditional values.

Athens, its primary rival, supported democracy and maritime power. After nearly three decades of conflict, Sparta was victorious.

Its victory in 404 BC, achieved with Persian support and the destruction of the Athenian navy, placed it at the head of Greece.

What were the causes of the Battle of Leuctra?

After its victory, Sparta took control of its former allies as it installed garrisons and enforced loyalty through force.

One of the most shocking examples occurred in 382 BC, as a Spartan commander, Phoebidas, seized the Theban acropolis in a surprise attack.

The city’s traditional leaders had been expelled, and a puppet regime had been installed.

Eventually, Theban patriots led by Pelopidas expelled the Spartans and restored local rule, and as a result, after they had regained their independence in 379 BC, the Thebans rebuilt the Boeotian League and prepared for retaliation.

Led by Epaminondas and Pelopidas, they formed new alliances and reorganized their army.

For several years, Sparta attempted to reassert control, but its efforts only hardened Theban resistance.

Tensions reached a breaking point in 371 BC. At a pan-Hellenic peace conference, Epaminondas demanded that Thebes be recognised as the leader of all Boeotia.

The Spartan delegation rejected this claim and refused to sign a common treaty, and as a result, King Cleombrotus marched north with a large army.

His goal was clear: he planned to destroy Theban power before it could grow further.

When Cleombrotus crossed into Boeotia through Phocis, he hoped to avoid detection.

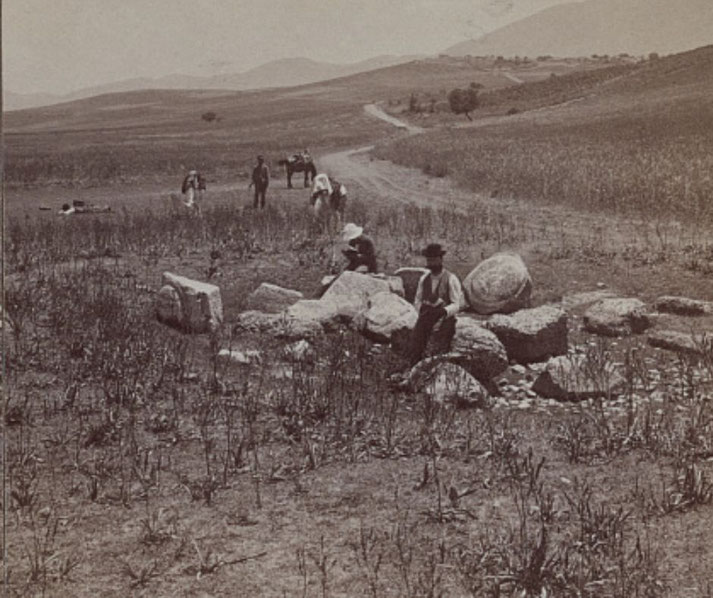

His troops advanced quickly and arrived near the village of Leuctra. Although the location had little strategic value before, it became the site of one of the most important battles in Greek history.

Overview of the two sides

On the morning of the battle, the Spartans sent nearly 10,000 men. Among them were approximately 600 to 700 Spartiates, who formed the core of Sparta’s forces, though the exact number remains debated by historians.

Their king, who was Cleombrotus I of the Agiad line, took command. As usual, they placed their best troops on the right flank of the phalanx.

This traditional structure had served them well for centuries. Allied contingents from the Peloponnesian League formed the rest of the line, which included the royal bodyguard of 300 hippeis.

In contrast, the Theban army was smaller. Estimates suggest it contained approximately 6,000 to 8,000 men.

Epaminondas led the Theban forces and knew he could not win by the usual methods.

Instead of copying the standard hoplite formation, he placed his best troops on the left.

Most important among them was the Sacred Band, which was a unit of 300 elite warriors known for their skill and unity.

The unit, which was traditionally attributed to Gorgidas around 378 BC, was composed of 150 pairs of male lovers, though the exact structure at Leuctra may not have been so strictly defined.

To make his left wing more powerful, Epaminondas intentionally arranged it fifty men deep, much deeper than the usual twelve.

He placed his weaker allies and lighter troops in the centre and right, where they would engage less heavily or hold position.

This plan aimed to defeat the Spartan elite quickly and roll up the enemy line before it could respond.

It was a risky strategy. No other Greek commander had tried it.

What happened on the day of battle

As both armies formed up, the Spartans assumed that the Thebans would follow convention, which meant that they expected a simple contest of strength.

However, the Theban left moved forward quickly. Epaminondas led the charge himself, supported by the Sacred Band and the best Boeotian hoplites.

Their concentrated formation hit the Spartan right with great force.

At first, the Spartans held their ground, but the deep formation of the Theban column put pressure on the Spartans to an extent they had not faced before.

During the clash, King Cleombrotus was killed in action, which left the Spartan command confused.

Soon, their right wing began to collapse under the strain.

Meanwhile, the centre and right of the Theban line remained less active. Their task was to hold position and delay contact, but once the Spartan right crumbled, the Theban left turned inward.

They struck the exposed flank of the remaining enemy troops, which quickly caused panic.

Quickly, the rest of the Spartan army retreated, and at least 1,000 men were left dead on the field.

According to Diodorus, about 400 were full Spartiates, which was a serious blow to a class already in declining numbers.

Many modern scholars, who disagree about whether that figure may have been exaggerated, agree that such losses greatly weakened Sparta's military capacity.

The consequences of the Spartan defeat

Immediately after the battle, the Greek world was stunned because Sparta had lost in open battle.

The defeat ended Sparta's long reputation for being unbeatable. Cities that once submitted out of fear began to question Sparta’s authority and its political control declined quickly.

More damaging than that was the loss of status among the casualties. The Spartiates had already been shrinking significantly in numbers and suffered a blow they could not recover from.

Their strict citizenship rules prevented new warriors from filling the gaps. For the first time, Sparta struggled to raise an army from its own citizens.

Plutarch later observed that by his own time, reportedly fewer than one hundred Spartiates remained.

In the years that followed, Thebes quickly took advantage of the opportunity created by the Spartan loss.

Under Epaminondas, it launched campaigns into the Peloponnese. In 369 BC, Epaminondas personally led the founding of the city of Messene, which effectively freed the Messenian helots, took away a key source of food and labour from Sparta.

The Arcadian League also formed during this period, further containing Spartan power.

Sparta never recovered its strength. Although Theban control also proved short-lived, the damage had been done.

The gap in power in Greece largely remained unresolved until Macedon rose under Philip II.

His later reforms, which included the use of deeper formations and concentrated force, followed Epaminondas' example.

Many historians now view Leuctra as a turning point that changed the future of warfare.

The Battle of Leuctra overturned a century of Spartan control and showed that new tactics could defeat established methods.

Arguably, among the many battles of the ancient world, none so clearly changed the balance of power in a single day.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.