Manipulating history: how Ramses the Great lied about the cataclysmic Battle of Kadesh

During the reign of Ramses II, one military encounter received more public attention than any other: the Battle of Kadesh.

It was fought around 1274 BCE between the Egyptians and the Hittites, and it became the subject of an organised state propaganda campaign unlike anything previously seen in Egyptian history.

Across his temples, Ramses ordered large inscriptions, detailed reliefs, and dramatic accounts that praised his battlefield decisions and highlighted his personal bravery in heroic verses.

The claim of Egyptian triumph was conveyed separately through temple reliefs. For centuries, this version of events influenced both popular and academic opinion about the battle.

However, a close study of the battle’s conduct, its immediate outcomes, and the limited but valuable Hittite records casts serious doubt on Ramses’ narrative.

The Battle of Kadesh offers one of the clearest examples of a ruler rewriting history for political advantage.

Background of the battle

Following the collapse of Egyptian control over Syria during the Second Intermediate Period, the 18th Dynasty pharaohs had gradually reasserted their influence over the region.

By the time Ramses II came to power in the 19th Dynasty, control of Syrian cities had become a key source of prestige and income.

However, these cities also lay within the Hittite area of control. From their capital at Hattusa, the Hittites had built a powerful empire under leaders such as Suppiluliuma I and Muwatalli II.

These kings had either forced or persuaded many Syrian rulers to abandon Egyptian allegiance.

As a result, conflict over this buffer zone was inevitable.

After consolidating his rule in Egypt and launching several campaigns into Canaan, Ramses II set out to recapture Kadesh, which was a militarily valuable city near the Orontes River.

Kadesh controlled access to key trade routes and offered a strong military base for further expansion into Syria.

Ramses led a massive force, reportedly consisting of four divisions named Amun, Re, Ptah, and Set, along with thousands of chariots.

His aim was to strike quickly and reassert Egyptian authority over the rebellious city.

Unbeknownst to him, however, the Hittite king Muwatalli had already expected this move and had prepared an ambush with a large coalition army, including allies from Anatolia and northern Syria.

What happened in the battle?

According to Egyptian sources, Ramses fell victim to a carefully planned Hittite deception.

Two enemy spies, posing as deserters, tricked the Egyptians into believing that the Hittite army was still far to the north.

Acting on this false intelligence, Ramses advanced too quickly and allowed his divisions to become scattered across the terrain.

When the Amun division made camp near Kadesh, it did so without the support of the other three divisions, which were still marching behind.

The Hittites, who had hidden their army behind the city, launched a surprise attack.

Their heavy chariotry crashed into the Egyptian camp, creating chaos and forcing many soldiers to flee.

Ramses, according to his own account, personally rallied a small group of warriors and fought off the Hittites until reinforcements from the Ne'arin, which was an Egyptian reserve force from Amurru, arrived.

The Egyptian inscriptions describe Ramses as turning the tide of battle by himself.

However, even those same texts admit that nightfall ended the fighting and that Ramses ultimately withdrew from Kadesh without capturing the city.

How do we know about the details of the battle?

Most of what is known about the Battle of Kadesh comes from Egyptian inscriptions.

These include the Poem of Pentaur and the Bulletin, both of which appear on multiple temple walls at Luxor, Karnak, Abydos, Abu Simbel, and the Ramesseum.

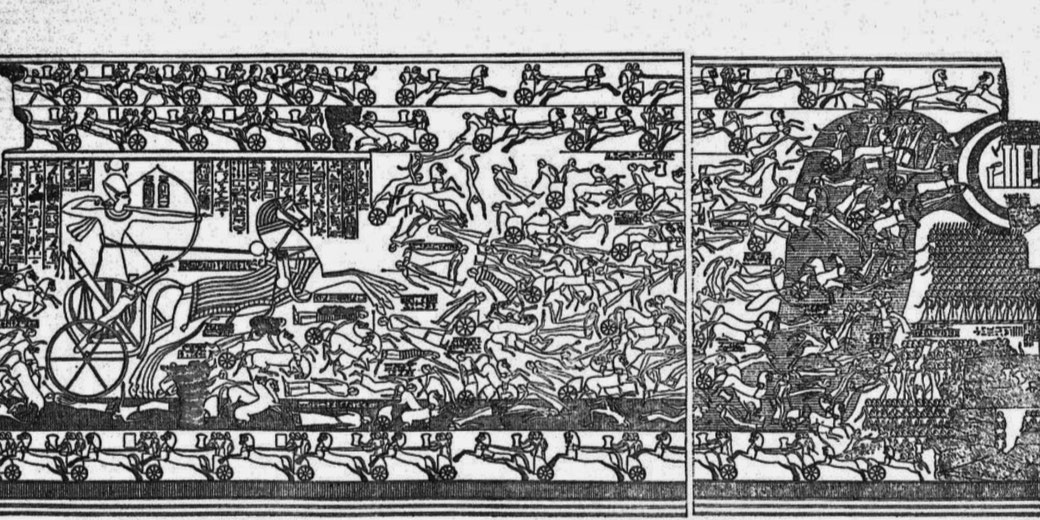

In addition to the texts, large carved reliefs show the scenes of battle in vivid detail.

These include chaotic fighting and fast-moving chariots and show Ramses in heroic poses as he defeats numerous foes.

The repetition of these accounts across different temples suggests a coordinated propaganda effort instead of presenting a neutral historical record.

The Poem and the Bulletin provide a relatively consistent sequence of events, although they exaggerate certain elements.

For example, they claim that Ramses faced thousands of enemy chariots alone and that the gods personally aided him.

The texts also describe the cowardice of Egyptian troops and the supposed blessing from the gods that allowed Ramses to prevail.

These literary flourishes, along with the stylised battle scenes, present a version of history crafted to glorify the pharaoh and promote the belief that the king had divine support.

However, they do not mention any long-term Egyptian occupation of Kadesh or a clear-cut military success.

Can we trust Ramses?

The self-promotion in Ramses’ accounts raises serious doubts about their reliability.

Egyptian kings often exaggerated their achievements, but Ramses took this practice to new levels.

By ordering the same version of the battle across multiple sacred sites, he ensured that future generations would see him as a heroic and victorious leader.

However, the actual results of the campaign tell a different story. Kadesh remained under Hittite control, and Ramses returned to Egypt without capturing the city.

This outcome contradicts the message of complete victory conveyed by the temple reliefs.

Furthermore, Ramses’ description of himself as the sole reason for the Egyptian army’s survival draws attention from his tactical mistakes.

He had allowed his divisions to spread out too far from each other, failed to verify intelligence, and made camp dangerously close to enemy territory without proper scouting.

Because he shifted the narrative to focus on his bravery and divine favour, Ramses avoided accountability and turned a military setback into a public relations success.

What do other sources say?

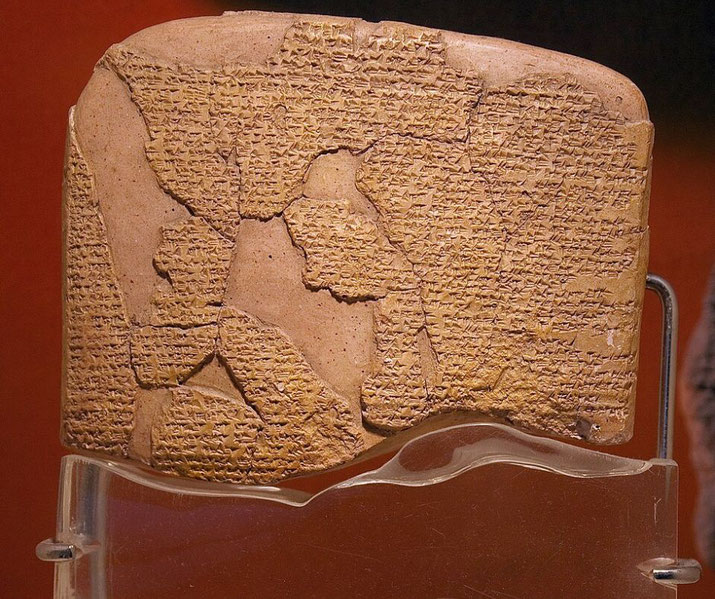

Unlike Egypt, the Hittites left fewer visual records of their military campaigns, but some written evidence survives.

A letter from Hattusa, preserved in the Hittite archives, discusses peace negotiations and confirms that Kadesh remained within the Hittite sphere of influence.

Later letters between Hattusili III (the brother and successor of Muwatalli II) and Ramses II shed light on diplomatic relations, including the famous peace treaty that was signed in the 21st year of Ramses’ reign.

This treaty, often described as the earliest known international peace agreement, implies that neither side achieved outright victory at Kadesh.

Hittite records also suggest that Muwatalli’s forces were far larger than Ramses claimed.

The presence of vassal states, allies, and reinforcements made the Hittite army a strong opponent.

The coordinated nature of the ambush indicates that the Hittites had superior intelligence and planning.

Egyptian descriptions of a sense of panic among soldiers, frequent desertion, and visible confusion on the battlefield support the idea that their army came close to collapse before the timely arrival of reinforcements.

Sorting truth from fiction

To piece together the real outcome of the Battle of Kadesh, one must strip away the self-serving layers of propaganda.

Ramses undoubtedly displayed courage during the battle, and his personal efforts may have stabilised the situation.

However, this should not obscure the fact that the Egyptian army was taken by surprise and suffered heavy losses.

The reliefs and texts imply a turning point in the battle, but do not show any conquest of Kadesh or permanent Egyptian control over the region.

Instead, the campaign ended in a military stalemate, followed by a gradual move towards diplomacy.

The decision to focus on religious monuments and poetic decorations suggests that Ramses understood the political power of narrative.

His inscriptions were less about historical accuracy and more about reinforcing his image as a warrior-king.

The absence of dissenting voices within Egyptian records further reveals how state-controlled history, which was carefully chosen, served the needs of the ruling elite.

If historians examine the few non-Egyptian sources and assess the practical results of the campaign, they can better separate reality from myth.

Aftermath of the Battle of Kadesh

In the years that came after the battle, neither the Egyptians nor the Hittites attempted another large-scale confrontation in Syria.

The heavy costs and inconclusive results of Kadesh had demonstrated the limits of military force in this contested region.

Eventually, a shift in policy led to diplomatic engagement. Around 1259 BCE,

Ramses II and Hattusili III made official a peace treaty that confirmed the existing borders and included clauses on mutual defence and the return of fugitives.

Copies of the treaty survive in both Egyptian hieroglyphs and Hittite cuneiform, which provides rare bilateral confirmation of terms.

This treaty did not result from a victorious campaign, but from the practical recognition that further fighting would risk more losses without clear gains.

Ramses married a Hittite princess as part of the agreement, further strengthening the new relationship between the two powers.

Publicly, Egyptian inscriptions presented this marriage as a sign of Ramses’ status and power, but it also acknowledged the growing influence of Hattusa.

The battle’s outcome, though publicly disguised, had set the stage for Egypt’s long-term shift towards diplomacy over territorial expansion.

What can we conclude?

The Battle of Kadesh illustrates how rulers can manipulate public memory to preserve their reputation.

Ramses II created a version of history in which he alone faced overwhelming odds, and emerged victorious.

This narrative, repeated across temple walls for generations, blurred the line between history and propaganda.

Yet, the military and diplomatic records tell a different story: a flawed campaign that ended in stalemate and was followed by political compromise.

Modern historians must weigh large inscriptions against archaeological evidence, foreign correspondence, and political outcomes.

In doing so, they uncover a more balanced account that reveals Ramses’ skill as a warrior as well as a master of image-making.

The real impact of Kadesh lies less in its tactics and more in its important lesson about how political authority, selective memory, and state propaganda can influence the historical record.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.