How Octavian crushed the combined forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra at Actium

Off the western coast of Greece, on 2 September 31 BCE, Octavian defeated the combined naval forces of Mark Antony and Cleopatra VII in a battle that helped decide the fate of the Roman Republic.

The battle took place near Actium, a narrow coastal area beside the Ambracian Gulf, where Antony had camped with a large fleet and thousands of troops.

As Octavian’s ships closed in under the command of Marcus Agrippa, the struggle that followed destroyed two of Rome’s most powerful rivals and removed the final obstacle to Octavian’s rise as the Republic’s unchallenged ruler.

Why were Octavian and Mark Antony at war with each other?

After Julius Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE, his supporters and enemies competed for control of the Roman state.

Within a year, three men, Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus, had formed the Second Triumvirate with official approval from the Senate.

Their goal was to punish Caesar’s killers and secure power, which they pursued by launching military campaigns and executing opponents across Italy and the provinces.

Over time, their alliance became unstable. By 40 BCE, Antony had established himself in the eastern Mediterranean, where he had aligned himself with Cleopatra and had governed Rome’s eastern provinces from Alexandria.

At the same time, Octavian strengthened his base in Italy and presented himself as a defender of Roman traditions.

Growing hostility between the two deepened after Antony distributed Roman territory to Cleopatra’s children, raising doubts about his loyalties.

Soon afterwards, Octavian obtained a copy of Antony’s will, which had been deposited in the Temple of Vesta and showed that Antony wished to be buried in Egypt, recognised Caesarion as Julius Caesar’s legitimate son, and intended to legitimise Cleopatra’s children as rulers.

Octavian made the document public and accused Antony of betraying Roman interests, which led him to arrange for the Senate to declare war on Cleopatra to avoid framing the conflict as a civil war between Roman citizens.

By shifting attention to a foreign queen, he turned public sentiment against Antony and ensured Senate approval for military action, though the campaign clearly targeted them both.

How both sides prepared for the final showdown at Actium

During the months that led up to the battle, Antony had concentrated his fleet inside the Ambracian Gulf, where he had fortified his camp near Actium and had gathered eastern allies.

His forces were reported to include more than 500 warships and tens of thousands of soldiers.

Cleopatra contributed money, men, and approximately 60 to 80 ships from Egypt, which allowed Antony to supply his position and prepare for a major naval confrontation.

Meanwhile, Octavian followed a different strategy: he chose not to seek a direct confrontation early and authorised Agrippa to disrupt Antony’s supply lines by capturing key ports along the western Greek coastline, which steadily diminished Antony’s access to food and reinforcements.

Agrippa’s swift victories at Leucas, Patrae, and Methone had isolated Antony’s fleet inside the gulf and had placed pressure on his commanders to act.

At the same time, Octavian regularly used political attacks on Antony’s decisions and character.

He circulated claims that Antony had abandoned Roman customs, surrendered his independence to Cleopatra, and intended to move the Roman capital to Alexandria.

As support for Antony weakened, people who switched sides began to weaken his command structure.

Most client rulers avoided openly switching sides and delayed action or withheld support, which significantly weakened Antony’s strategic position.

Over time, the combined effect of starvation and disease, coupled with widespread desertion, damaged both the morale and the stability of his camp, which meant the defensive works, which were constructed by Lucius Caninius Gallus at Actium, could not make up for dwindling provisions or declining loyalty.

How much stronger were Antony’s forces before the battle?

At the start of the campaign, Antony commanded a larger and more heavily armed fleet.

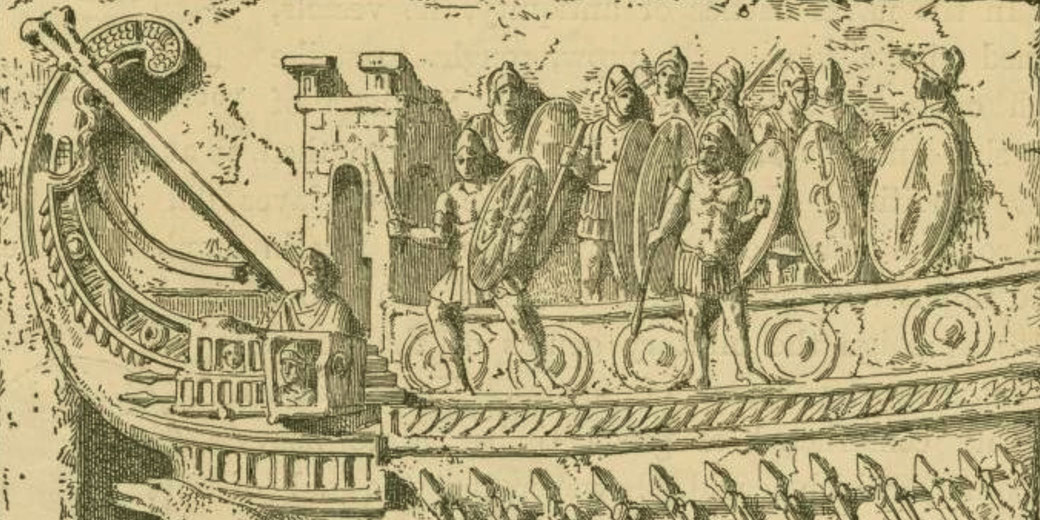

His ships included quinqueremes and deceres, which carried towers, archers, and marines trained for close combat.

In total, he had between 500 and 700 vessels, supported by allied troops from Judea, Syria, Pontus, and Egypt.

Cleopatra’s presence added financial strength and additional ships, which made his fleet one of the most powerful naval forces in the eastern Mediterranean.

However, Agrippa understood the disadvantages of engaging Antony in traditional combat.

Instead of matching his fleet in size or weight, he deployed smaller, faster vessels that could operate in shallow waters and outmanoeuvre heavy warships.

He had trained his crews to slash rigging, disable sails, and avoid boarding actions, which helped them survive long enough to wear down enemy crews.

His earlier victories at Mylae and Naulochus had shown the effectiveness of such tactics.

Gradually, Antony’s larger numbers became less useful. His ships required large crews and steady supplies, but the blockade made resupply difficult, as many of his client kings delayed action or refused to assist, while others defected to Octavian.

Confidence in Cleopatra’s involvement also weakened the fleet’s unity, as Roman officers grew suspicious of her influence over strategy.

As a result, Antony’s superior fleet became vulnerable to disruption.

What happened at the Battle of Actium?

On 2 September 31 BCE, Antony launched his fleet in an attempt to escape the blockade.

His plan required a breakout through the narrow exit of the Ambracian Gulf, followed by a rapid retreat southward where he could regroup with his land forces and Egyptian treasure ships.

He arranged his largest vessels at the centre and placed his faster ships along the flanks to protect their escape.

Agrippa held the line across the mouth of the gulf and attacked Antony’s flanks.

Octavian’s ships avoided direct boarding and instead used grappling lines, slings, and manoeuvres to break up enemy formations.

Fighting continued for hours without a clear result, as the two sides clashed in tight waters under heavy missile fire and boarding attempts.

The battle began in the early morning and unfolded in light winds, which hampered the movement of Antony's heavier ships.

Then Cleopatra’s fleet sailed out of formation and broke southward, where it slipped through the chaos without engaging the enemy.

Her departure may have been prearranged with Antony and had allowed her to escape with her treasure ships, which led Antony, who saw her movement, to choose to abandon the battle and follow with a small escort.

His sudden retreat shocked his officers, who found themselves without leadership in the middle of a naval engagement.

Octavian’s fleet took advantage of the confusion, surrounded the remaining ships, and either captured or destroyed most of the fleet.

Why did Antony and Cleopatra lose at Actium?

Antony’s failure largely came from a series of poor decisions, since he had maintained his position at Actium for too long, which allowed Octavian to surround and weaken him gradually.

His reliance on massive warships, which was seemingly impressive in power, proved difficult to manoeuvre and supplied little advantage in confined coastal waters.

Most critically, he relied on a single major confrontation at sea without fully considering the weaknesses of his command structure or the unreliability of his officers.

Cleopatra’s presence appeared to create additional problems. Many Roman commanders disliked her influence, and rumours about her intentions damaged confidence.

Once she fled the battle, uncertainty spread among the ranks. Antony’s sudden decision to follow her, rather than continue the fight, destroyed any remaining order and left his men stranded.

Agrippa’s tactics ensured that Antony never gained the upper hand. Agrippa broke down Antony’s advantages over time, which he did by trapping the fleet, cutting off supplies and provoking mistakes.

Octavian’s refusal to rush the battle allowed him to maintain pressure without overcommitting, which ultimately gave him the freedom to exploit every error that Antony made.

Why the Battle of Actium was so significant

After the battle, Octavian moved quickly to invade Egypt, which led to both Antony and Cleopatra dying by suicide within a year, with him dying on 1 August and her dying around 10 or 12 August 30 BCE, possibly using an asp to end her life.

Egypt became a Roman province under Octavian’s direct control. Its grain harvests and treasure added to his growing resources, while his enemies’ deaths removed any remaining opposition.

Soon after, Octavian returned to Rome, and in 27 BCE he staged a formal restoration of the Republic and relinquished extraordinary powers in appearance, though he retained control over the army, the treasury, and the most important provinces.

The Senate rewarded him with the title Augustus, which indicated his authority without appearing to end the Republic.

His rule began the Principate, an era of imperial power that replaced the older system of shared magistracy.

The Battle of Actium was the final moment of resistance against Octavian’s path to one-man rule.

By removing Antony and Cleopatra from the stage, he ended decades of civil war and built a new political structure under his personal command.

His victory at Actium helped secure territorial control and the public support of the Roman people, who now looked to him for peace and a stable government that promised continuity.

Later, Octavian issued commemorative coinage and commissioned monuments such as the Tropaeum Augusti to celebrate his triumph, which further reinforced his image as the restorer of Rome.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.