The remarkable discovery of the Amarna Letters, the personal correspondence of the pharaohs

Among the most valuable sources for understanding international diplomacy during the Late Bronze Age, the Amarna Letters have preserved the personal communications exchanged between the Egyptian pharaohs and the kings and rulers of neighbouring states.

Found at the site of Akhetaten, the short-lived capital city established by Pharaoh Akhenaten in the 14th century BCE, the tablets had survived beneath the sands of Middle Egypt for over three thousand years.

Once decoded, they exposed how rulers managed foreign alliances, negotiated marriages, arranged military aid, and requested shipments of gold or grain, plus so much more.

When were the Amarna Letters written?

In the final decades of the 18th Dynasty, Egypt experienced a period of unusual religious experimentation and administrative disruption.

The Amarna Letters come from this time, roughly from 1350 to 1330 BCE. The majority of the letters date to the reign of Akhenaten, who ruled from approximately 1353 to 1336 BCE.

A smaller number likely originated during the final years of his predecessor, Amenhotep III, and a handful may have been sent during the brief and chaotic reigns of Akhenaten’s successors, including Smenkhkare, Neferneferuaten, and Tutankhamun.

During these decades, Egypt maintained an extensive network of influence that stretched across the Levant and deep into Mesopotamia.

The correspondence records the management of this network. Letters from foreign kings appealed to the pharaoh for assistance, acknowledged shared loyalties, or complained about Egyptian governors in their regions.

As Egyptian power weakened during Akhenaten’s reign due to internal upheaval, local rulers increasingly expressed anxiety about growing threats from outside powers and rising local warlords.

As such, the letters offer a window into this fragile balance and reveal how imperial diplomacy struggled under the strain of domestic transformation.

What language were the letters written in?

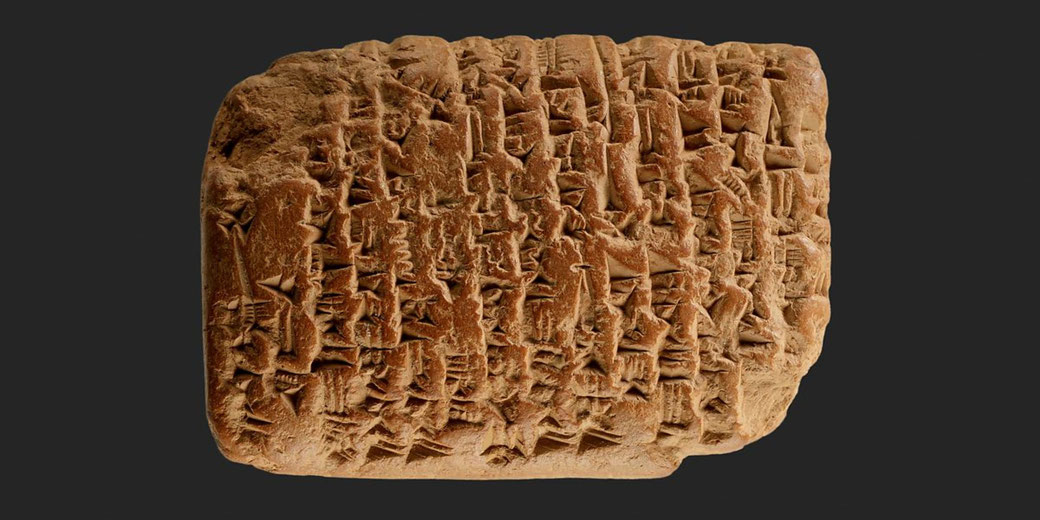

Rather than Egyptian, the Amarna Letters were written in Akkadian cuneiform, which was the diplomatic common language of the time.

Akkadian originated in Mesopotamia and had long was the common written medium across empires from Babylon to Hatti.

Its grammar and vocabulary had been standardised centuries earlier, and scribes across the Near East received training in its use as part of their education.

Even regions that did not speak Akkadian adopted it for official correspondence, much like Latin in medieval Europe.

Egyptian scribes who worked in the foreign office at Akhetaten adapted their own writing materials and techniques to suit cuneiform.

The tablets were typically made of local Egyptian clayd an showed clear signs of stylus impressions that followed the conventions of Mesopotamian script.

Many tablets contain grammar quirks that suggest the scribes learned Akkadian as a second language and sometimes relied on Egyptian sentence patterns.

In some letters, especially those sent from Canaanite city-states, a regional version of Akkadian appeared, blended with West Semitic words and phrases that reflected the speaker’s native tongue.

This mix of formal protocol and regional expression gave each message a distinct flavour.

What was written in the Amarna Letters?

The content of the letters varied depending on the status of the sender and the relationship between the courts.

Correspondence between Egypt and powerful independent kingdoms such as Mitanni, Babylonia, Hatti, and Assyria focused on affirming equal status between rulers.

Such letters frequently discussed dynastic marriages, with foreign kings requesting Egyptian princesses as wives, and negotiations over gifts of gold, horses, ivory, and other high-status items.

Egyptian rulers typically refused to send their daughters abroad, and the letters document how foreign rulers protested this policy and expressed offence at perceived insults.

In contrast, letters from vassal states in Syria and Canaan tended to follow a more servile tone.

Local governors referred to themselves as “the dust under the feet of the king” and pleaded for military aid, supplies, or relief from rival factions.

Several letters describe raids by groups such as the Habiru, often portrayed as outsiders who disrupted trade routes and attacked towns.

The Egyptian court received frequent complaints about their own officials, accused of corruption or neglect.

Some vassals attempted to outdo each other in flattery, hoping to gain favour and resources.

Occasional letters included urgent calls for military intervention, such as those from Rib-Hadda of Byblos.

His detailed account of political manoeuvring gave historians valuable information, and his descriptions of betrayal illustrated how alliances shifted during the unstable situation in the eastern Mediterranean in the late 14th century BCE.

The most famous authors of the surviving letters

Rib-Hadda, the governor of Byblos, authored at least sixty letters, which means that he was the single most prolific correspondent.

His pleas for assistance were laced with frustration and loyalty, and it forms a continuous narrative of decline as Egyptian influence in the region eroded.

He accused rival city leaders of treachery and warned that Byblos would fall without swift support.

His persistence and eventual silence suggested a tragic end to a loyal servant abandoned by his imperial masters.

From the royal courts of the great powers, kings such as Tushratta of Mitanni and Burnaburiash II of Babylon sent letters seeking diplomatic balance with Egypt.

Tushratta’s letters showed a keen awareness of the need to maintain close ties through intermarriage and lavish exchanges.

He referred to earlier arrangements made with Amenhotep III and expressed dissatisfaction with Akhenaten’s less enthusiastic treatment of their alliance.

Burnaburiash focused on fairness and equivalence, repeatedly requesting that Egypt match his own generous gifts and honour prior agreements.

In one letter, he protested the poor quality of gold received from Egypt, accusing the pharaoh of disrespect.

Several tablets originated from the Hittite court. Though fewer in number, they highlighted the growing power of the Hittites under Suppiluliuma I and tensions between the two powers and indicate the military confrontations that followed in the 13th century BCE.

How the Amarna Letters were rediscovered

In the late 19th century, local villagers near the ruins of el-Amarna (ancient Akhetaten) began uncovering unusual clay tablets while digging for bricks and other construction material.

News of the finds quickly reached European antiquities dealers, and a number of tablets entered the international market without proper excavation records.

By 1887, formal archaeologists began systematic investigations of the site, and more letters were recovered from the archives of official buildings, especially the Bureau of Correspondence of Pharaoh.

The early finds triggered a rush among scholars, particularly in Germany and Britain, to translate and study the cuneiform tablets.

The decoding of Akkadian had already progressed by the mid-19th century, so the task of understanding the letters moved quickly. H

ugo Winckler, Knudtzon, and other language experts led the early publication of the texts.

When historians compared them with diplomatic archives from other regions, they confirmed the authenticity of the letters and situated them within a much larger international background.

Many of the original tablets now reside in the collections of major institutions such as the British Museum, the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Ongoing excavations and satellite studies of the Amarna site have provided additional information about the scribal schools and administrative offices where the letters were written.

Today, the Amarna Letters are one of the most direct sources for understanding how Egyptian power operated on a global scale and how fragile that influence became when internal disorder weakened the ability to respond.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.