Why Alexandria was the most important city in the ancient world

Of the many important cities of antiquity, none surpassed Alexandria's influence and prosperity in the Mediterranean world.

This city had been built at the command of Alexander the Great in 331 BCE, and it rapidly developed into a beacon of trade and scholarship that projected considerable political power.

For several centuries, it stood at the heart of Mediterranean civilisation and attracted some of the greatest minds and wealth of the ancient world.

The importance of Alexandria's location

At the northern edge of Egypt, where the Nile Delta met the Mediterranean Sea, Alexandria controlled a location that enabled it to control trade and communication between continents.

Because of its location, merchants could move Egyptian grain across the eastern Mediterranean while returning with goods from Greece, Asia Minor, and Phoenicia.

Each exchange strengthened Alexandria's role as the main centre of international trade.

To the northwest, the island of Pharos created a natural barrier that shielded Alexandria’s twin harbours from rough seas.

Early on, builders constructed the Heptastadion, a causeway that linked Pharos to the mainland and formed two separate harbours.

One opened westward for summer sailing, the other opened eastward for winter voyages, and as a result commercial activity continued all year.

Importantly, canals had linked Alexandria to the Nile, which allowed grain and other agricultural goods to reach the city quickly, and since grain was vital to the diets of people across the Roman Empire.

Alexandria’s control over its export made the city critical to Rome’s stability.

As such, Roman emperors had stationed troops in the city to protect this lifeline and prevent disruption.

At its height during the Roman period, Alexandria had likely housed between 500,000 and 1 million residents, making it the second-largest city in the Roman Empire after Rome itself.

The genius of Alexandria's planning and design

From its foundation, the city’s planners introduced a street grid that brought clarity and order to urban life and established a large scale across the city.

Wide streets lined with columns intersected at regular points, creating public squares, housing blocks, and markets that followed the same regular layout.

At its centre, the Canopic Way likely formed the main road and connected the royal palace precinct to major temples and civic buildings.

Along this route, state processions and festivals could proceed without obstruction.

To the east, the royal quarter held the palaces of the Ptolemies and their court.

Within that district stood the Mouseion and the Great Library. The Mouseion, supported by the state, operated as a scholarly institute that housed resident scholars, supported research, and operated as a centre for scientific and literary study.

Scholars who lived and worked there received accommodation, food, and access to one of the greatest collections of texts ever assembled, and as a result, Alexandria quickly developed a reputation as the intellectual centre of the ancient world.

Some ancient estimates claimed that the Great Library housed between 400,000 and 700,000 scrolls, covering texts from Egypt, Greece, Persia, India and Mesopotamia.

To the south, the Serapeum towered over the lower city. Built in honour of Serapis, a god invented by the early Ptolemies to unify Greek and Egyptian religious beliefs.

Its large statue halls, sacred texts, and rituals attracted worshippers from across Egypt and further afield.

The Serapeum included lecture halls, reading rooms, and a daughter library that added to the library's collection and linked state religion with scholarly life.

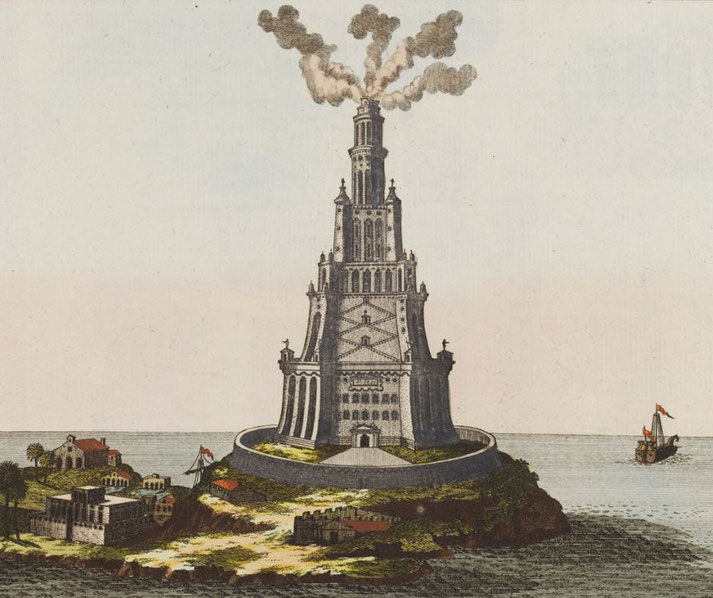

Near the harbour mouth, the Lighthouse of Alexandria, which had been built during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, likely stood over 100 metres tall, shone across the sea and guided sailors day and night with its bronze mirrors.

Traditionally attributed to the architect Sostratus of Cnidus, the lighthouse featured three tiers, square, octagonal, and cylindrical, and may have used a ramp or spiral staircase to carry fuel to the beacon chamber.

In practical terms, it ensured safe passage into the harbours. Culturally, it represented Alexandria's leading role at sea.

The incredible wealth that flowed into the city

At the height of its prosperity, Alexandria operated as a global trade centre where merchants, ships, and currencies moved in large quantities.

Tax collectors stationed at the harbours collected taxes on all incoming and outgoing goods, ensuring a constant flow of revenue to the state.

As a result, the royal treasury stayed full, and public works expanded.

From Egypt’s interior, grain travelled down the Nile and passed through Alexandria before being shipped to cities across the Roman world.

At the same time, emperors closely monitored Alexandria to prevent famine or rebellion.

From Arabia and India, traders delivered incense, spices, gemstones, and silk. Once these goods reached Red Sea ports, caravans brought them to the Nile and then to Alexandria.

At the same time, workshops in Alexandria made papyrus scrolls, linen, glass, and perfumes for export.

Every stage of this trade enriched the city and expanded its international reach.

Evidence of this wealth appears in coin hoards buried across Egypt. Many of these contain silver drachmas and gold staters minted in Alexandria, which circulated widely across the Mediterranean.

The different religious groups in Alexandria

Among the most varied cities of the ancient world, Alexandria brought together Egyptians, Greeks, Jews, Syrians, and others who maintained different religious practices.

Greek religion was the official public religion, and public ceremonies celebrated gods such as Athena, Zeus, and Serapis.

At the same time, Egyptian temples continued to honour traditional deities including Isis and Horus. Both sets of worship practices occurred side by side.

The Jewish community made up a large part of Alexandria's population, many of whom spoke Greek and used the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures.

According to tradition, the Septuagint was translated in Alexandria by seventy-two Jewish scholars during the reign of Ptolemy II, to provide a Greek version of the Hebrew Torah for the royal library.

Jewish leaders governed their internal affairs and often held positions of influence under both Ptolemaic and Roman rule.

Occasionally, tensions flared between Jews and Greeks, especially during periods of political uncertainty.

The Jewish-Greek riots of 38 CE were provoked in part by the policies of the Roman governor Aulus Avilius Flaccus and led to mass violence and expulsions, showing how the city's mix of peoples could cause instability.

Christianity also became important early on in Alexandria. According to Church tradition, Saint Mark arrived in the first century CE and established a Christian congregation.

By the second century, theologians such as Clement of Alexandria and Origen were teaching there, and their ideas influenced the early Church and later theological debates.

From the fourth century onward, Alexandria became a battleground for competing religious beliefs.

As imperial policy shifted in favour of Christianity, pagan temples closed, and public discourse narrowed.

The violent death of Hypatia in 415 CE was carried out by a Christian mob and caused a collapse in tolerance and ended centuries of philosophical tradition in the city.

During the Byzantine era, Alexandria remained a centre of theological debate, which included the rise of Arianism and the Coptic Church’s resistance to imperial orthodoxy.

The famous people who called Alexandria home

During its peak, Alexandria attracted individuals whose work influenced fields such as astronomy, mathematics, literature and politics.

Euclid, who probably wrote his Elements there, laid out the principles of geometry in a form still studied today.

Eratosthenes, who also worked as librarian, likely used geometry and shadow measurements to calculate the Earth’s circumference with remarkable accuracy.

Herophilos, who likely performed some of the earliest recorded human dissections in Alexandria along with Erasistratus, identified the brain rather than the heart as the centre of intelligence.

Astronomers such as Ptolemy, who refined theories of the cosmos and recorded star positions, relied heavily on earlier work by figures like Hipparchus, who conducted his observations in Rhodes.

Ptolemy’s Almagest, written in Alexandria, remained the main guide to astronomy for over a thousand years.

Elsewhere in the Library, poets such as Callimachus created large catalogues of texts and works of literature, while Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria tried to combine Hellenistic philosophy with Jewish theology.

His writings would later influence early Christian and Islamic thinkers.

At the highest level of power, Queen Cleopatra VII, who was fluent in several languages and who was educated in science, literature and politics, held great influence.

Cleopatra VII personally supported Alexandrian science, inviting scholars to her court and encouraging intellectual life, although the Mouseion’s institutional influence had likely diminished by her reign.

She aligned with both Julius Caesar and Mark Antony in a bid to protect Egypt’s independence, and, although her efforts failed, her intelligence and leadership kept Alexandria at the centre of imperial affairs until the very end of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Why Alexandria fell into decline

Following its annexation by Rome in 30 BCE, Alexandria lost the royal support that had funded its cultural and scientific institutions.

Though still economically active, the city gradually became more dependent on Roman policies.

During Caesar’s siege of the city in 48 BCE, fires had damaged warehouses near the port that had reportedly held scrolls, though the extent of destruction to the Great Library itself is uncertain.

Later, unrest under emperors such as Caracalla and Aurelian led to further destruction.

From the third century CE onward, political instability and religious violence damaged Alexandria’s position as a centre of learning, and as Christian emperors introduced stricter religious controls, traditional temples closed and scientific study lost its public support.

With each new conflict, more damage accumulated.

In 641 CE, Arab armies under the Rashidun Caliphate took Alexandria. Although it remained occupied, the new rulers founded their capital further inland at Fustat.

Trade routes shifted and political attention moved away. Over time, Alexandria lost its role as Egypt’s primary city.

Although the Arab conquest ended Byzantine rule, Alexandria retained some of its commercial relevance until the rise of Cairo diverted administrative and economic activity inland.

Also, repeated earthquakes damaged buildings along the coast, which caused parts of the ancient harbour and the Pharos Island sank, and eventually the great lighthouse collapsed.

Traders, scholars, and patrons moved elsewhere, and Alexandria became a memory of a city that once dominated the ancient world.

However, underwater excavations, which were led by Franck Goddio in the 1990s, uncovered remnants of the ancient Royal Quarter, including statues, columns and temple ruins long thought lost to the sea.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.