Who was Alexander the Great’s real father?

Ancient sources claimed that Alexander the Great accepted or encouraged the belief that Zeus, rather than Philip II, was his real father.

This very strange declaration, which was actually supported by his own mother, shocked both his contemporaries and modern historians.

However, the claim seemed to be caused by a mixture of political manipulation and religious strategy during his reign.

Why did Alexander think that Zeus was his father?

Apparently, Alexander believed in his divine parentage from a very young age, and sources suggest that this belief stemmed from stories encouraged by his mother Olympias.

According to Plutarch, she told him that a thunderbolt struck her womb in a dream before her marriage and that Zeus visited her in the form of a serpent, which Philip saw in her bed.

Olympias was a known devotee of Dionysian cult practices that often included serpentine symbolism, and reportedly forbade Philip from touching her afterward.

These accounts, whether based on actual belief or political storytelling, provided Alexander with an otherworldly narrative that could distinguish him from ordinary mortals.

Ancient sources also recorded that Alexander’s birth coincided with several dramatic signs, including the destruction of the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus in 356 BCE, which some interpreted as evidence that a god had entered the world.

These omens added weight to the claim that Alexander had a special connection with the divine.

Over time, Alexander appeared to absorb this belief, as reflected in his actions and ceremonies.

In 331 BCE, during his time in Egypt, Alexander visited the oracle of Zeus-Ammon at Siwa, where priests reportedly gave him an oracle that confirmed divine favour.

The oracle had previously attracted rulers such as Cambyses II, and its statements held deep significance for both Egyptians and Greeks.

Although the priests' exact words remain unknown, ancient authors such as Arrian and Plutarch claimed that Alexander emerged from the temple convinced that Zeus had confirmed his divine paternity.

This episode strengthened his public embrace of the myth and influenced how he presented himself to others.

As a result, Alexander began to incorporate divine symbols into his image and expected others to address him in religious terms.

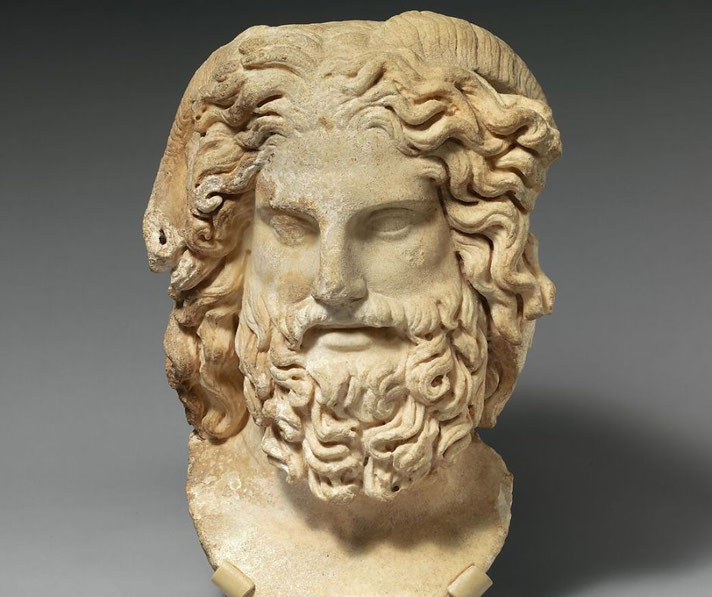

He encouraged portraits that displayed him with features of Zeus-Ammon, including the ram’s horn, and introduced customs such as proskynesis, which demanded that subjects bow before him.

The philosopher Callisthenes, who refused this act, later fell from favour and died in captivity under uncertain circumstances.

These practices reflected both Eastern traditions of divine kingship and Alexander’s growing conviction that he had a sacred role.

Coinage from this period showed Alexander with attributes linked to the gods, and court poets compared him to Heracles and Achilles.

In fact, his mother claimed descent from Achilles, while Philip traced his line to Heracles, both sons of Zeus.

These ancestral links explain why he no longer saw himself as an ordinary mortal but as someone chosen by a higher power to conquer the world and rule over many peoples.

The role of myth and divine ancestry in Ancient Greece

Myth functioned as a tool of authority in ancient Greek society, especially for those who claimed heroic or divine descent.

Many ruling families traced their ancestry to legendary figures such as Heracles or Perseus, and these connections provided both a sense of inherited authority and heroic lineage.

Macedonian kings already used this tradition to claim heroic status, and Alexander’s claim of divine parentage fit within this framework.

Greek religion accepted the idea that gods intervened in human affairs, especially to support individuals of remarkable ability.

Epic heroes such as Achilles and Odysseus received guidance from the gods. By claiming Zeus as his father, Alexander aligned himself with this heroic tradition and framed his military success as a continuation of divine will.

Public reactions to Alexander’s claim varied depending on cultural background.

Among Macedonians, the myth received doubt and sometimes open resistance, as traditional Greek society did not generally venerate living rulers as gods.

Cleitus the Black openly mocked Alexander's divine claims during a banquet in 328 BCE, which led to his death at Alexander's hands in a drunken rage.

However, among Egyptians, Persians, and others within his growing empire, divine kingship already existed as an accepted concept.

These subjects saw no contradiction in viewing Alexander as the son of a god and ruler of the world.

Alexander’s myth allowed him to unite diverse populations under a shared vision of sacred authority, which reduced the need for constant military force and encouraged voluntary submission.

This also helped stabilise his rule as he moved further from the Greek heartland and into culturally distinct territories.

The claim to divine ancestry also influenced the actions of his successors. After Alexander’s death, the Diadochi used the idea of his godlike nature to justify their own rule over different parts of his empire.

In fact, Ptolemy I placed Alexander’s body in Alexandria and constructed the Soma, a shrine that helped reinforce his claim to right to rule in Egypt.

The religious utility of the myth

The divine parentage myth gave Alexander access to multiple religious systems and allowed him to act as a sacred figure across many cultures.

In Egypt, his identification with Ammon linked him directly to the pharaonic tradition, while in Babylon, he entered the temple of Marduk and performed rituals expected of a king.

In India, he honoured local gods and performed rituals at major sanctuaries, as he used divine identification as a means to fit himself into each region’s belief structure.

Some Indian philosophers, such as the gymnosophists, reportedly mocked or dismissed his claims of divinity, which suggests that not all cultural encounters affirmed the myth.

By acting as a bridge between religious traditions, Alexander positioned himself as a kind of 'universal ruler'.

His religious flexibility allowed him to move from Greek to Egyptian to Persian practices without alienating his subjects.

In each case, the myth of Zeus as his father provided a narrative that could absorb local traditions while maintaining his own superiority.

In a similar way, Alexander built temples, conducted public sacrifices, and promoted the worship of his image, which created a form of imperial religion that connected political power with divine favour.

His subjects began to see him as both a military commander and a religious figure whose rule had universal significance.

Following his death in 323 BCE, many cities developed cults to honour Alexander as a hero or demigod.

Ultimately, the story of Zeus as Alexander’s father influenced both how he ruled and how others remembered him.

It offered sacred status in foreign lands, reinforced his control among rivals, and cloaked him in divine symbolism, which few other leaders could match.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.