How Alexander the Great's only son became a tragic pawn in a bloody struggle for the throne

Alexander IV of Macedon was born into an empire already on the verge of collapse. As the son of a legendary conqueror and an heir who had been born after his father's death to a large but unstable kingdom, his life unfolded under the control of regents and senior generals whose rivalries largely prevented his rule.

The dramatic death of Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great died suddenly in Babylon in June 323 BCE, aged just thirty-two, without naming a formal successor to his empire.

He had led a rapid series of campaigns that stretched Macedonian control from Greece to the banks of the Indus, but he then fell ill and probably died of a high fever after several days.

Ancient historians included Arrian and Plutarch, who offered different theories about the cause.

Some suggested typhoid or malaria, while others repeated the rumour that he had been poisoned.

At court, confusion and fear spread rapidly and widely because the absence of a clear heir created immediate tension.

Philip Arrhidaeus, who was his half-brother, lived under constant supervision and reportedly suffered from a mental disability, though the exact nature of his condition was uncertain, and few among the ruling elite saw him as a viable long-term ruler at that time.

Roxana was one of Alexander’s wives and was pregnant at the time of his death.

For that reason, the generals agreed to a dual monarchy in which Arrhidaeus would reign as Philip III and the unborn child, if male, would share the throne once born.

To prevent a complete collapse of unity, the general Perdiccas took charge as regent because he had held a senior command under Alexander and now assumed responsibility for both the royal family and the empire’s future.

Under his authority, the empire remained officially intact for a time, but powerful commanders who controlled provinces had already begun to act independently because many now looked for ways to increase their authority.

These men were generally known as the Diadochi, who included Ptolemy in Egypt, Antigonus in Asia Minor, Seleucus in Babylon, and Lysimachus in Thrace.

Being born into a political storm

Alexander IV of Macedon was born a few months later, probably around August 323 BCE, in Babylon.

From the moment of his birth, he became the focus of a fragile agreement. He was recognised as king in name but held under the control of regents who largely acted in their own interest.

His mother, Roxana, stayed under the protection of Perdiccas, but he had begun to take active steps to impose his authority on rival generals, whom he ordered to obey decisions made in the name of the kings.

One key move had been his attempt to marry Cleopatra, Alexander the Great’s full sister.

If successful, the marriage would likely have strengthened his connection to the royal family and strengthened his claim to speak for the Argead line.

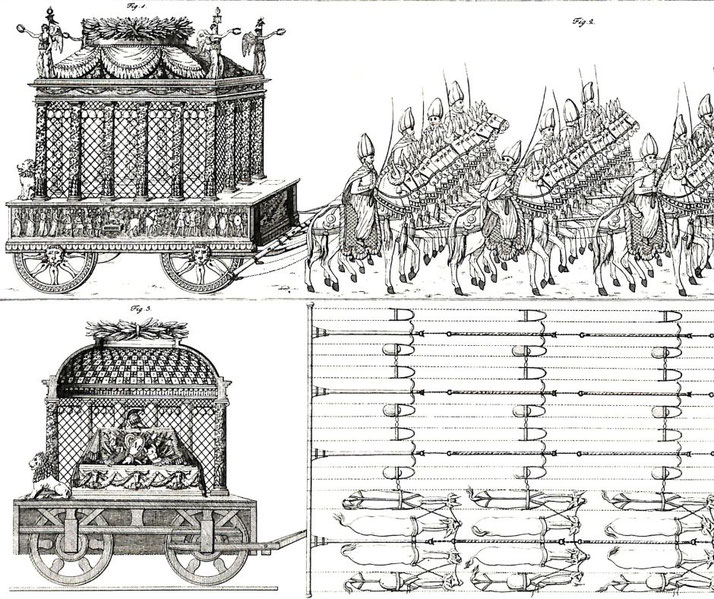

However, opposition to Perdiccas escalated quickly. In Egypt, Ptolemy seized Alexander’s body, diverted it to Memphis where he gave it an honoured temporary burial before its later transfer to Alexandria, and refused to obey Perdiccas' summons.

Elsewhere, Antigonus in Asia Minor ignored orders; meanwhile, Antipater in Macedon continued to control affairs in Europe.

Because Perdiccas had arguably stretched his power too far by attempting to invade Egypt in 321 BCE and punish Ptolemy, and because he had failed to cross the Nile and had faced disagreement among his officers, his own officers, including Seleucus, reportedly assassinated him.

Since the regency had largely collapsed again, Roxana and her infant son passed under the protection of Antipater, who brought them to Macedon.

On the surface, this seemed a move for safety. In reality, it placed the boy king in the hands of another powerful ruler who had no clear plans to surrender control of the empire.

Why Alexander was taken back to Macedon

For two years, Antipater acted as regent for both Philip III and Alexander IV. He generally ruled with stability and resisted provoking further civil wars.

However, his unexpected decision in 319 BCE to appoint Polyperchon as his successor triggered unrest because his son Cassander, who had expected to inherit the role, saw this as a betrayal.

Soon after, Cassander launched a campaign to challenge Polyperchon’s authority because he had won at least some support from Ptolemy and Antigonus.

He raised an army and took control of key regions. Polyperchon tried to win support by restoring democratic governments in Greek cities and invoked Alexander the Great's name.

However, since Polyperchon’s attempts failed, Cassander’s military success and his political support gave him increasing control over Macedon.

After Cassander captured Roxana and the boy king, by 317 BCE he had imprisoned them in the fortress of Amphipolis, which was a secure stronghold in eastern Macedon.

He did not yet openly claim the throne for himself, as many Macedonians still viewed Alexander IV as the rightful heir.

Instead, Cassander ruled as regent and delayed any formal declaration because he hoped to secure his position and to avoid rebellion.

To support his authority, he married Thessalonike, who was the half-sister of Alexander the Great.

That marriage, along with his control of the royal family, helped to present him as part of the Argead house.

Still, as the boy grew older, his presence became more dangerous.

The assassination of Alexander IV

Cassander had held Roxana and her son in confinement for several years. Their survival had given him limited political cover, yet their presence also threatened his position.

Eventually, a growing number of Macedonians expected the boy to assume full power as he approached adulthood.

In 311 BCE, Cassander and other successors agreed to a peace that officially recognised Alexander IV and promised to install him as king once he came of age, although this promise probably did not reflect their true intentions.

That agreement created immediate problems because it would force Cassander to give up power and possibly face punishment for past actions.

So, around 309 BCE, Cassander ordered the assassination of both Roxana and Alexander IV.

The exact method is unknown, but ancient sources such as Diodorus Siculus and Justin agree that the killings took place in secret, most likely within Amphipolis itself.

He hid their deaths for as long as possible because that delay allowed him to prepare for potential resistance and avoid unrest.

By the time news of the murders spread, few could realistically challenge Cassander, as the Argead dynasty effectively had no surviving heirs.

Olympias was the powerful mother of Alexander the Great, and she had taken custody of Alexander IV in 317 BCE, had ordered the execution of many of his enemies, and had already been executed in 316 BCE on Cassander's orders.

The Diadochi, who had once claimed to act in the name of Alexander the Great, now ruled as independent kings.

Every powerbroker who controlled him did so to increase their own authority, and in the end, his death became the last step in their long campaign to divide the empire.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.