A nation divided: The fiery conscription debates that shaped Australia's role in WWI

In Australia, the conscription of men for military service during World War One was a highly controversial issue. In the early years of the war, only those who volunteered were sent oversees to fight.

However, the Australian government wanted to change that by introducing forced conscription. The two referenda on the matter, held in October 1916 and December 1917, resulted in a defeat for the pro-conscriptionists.

This article will explore the reasons behind this strong opposition to conscription in Australia during World War One.

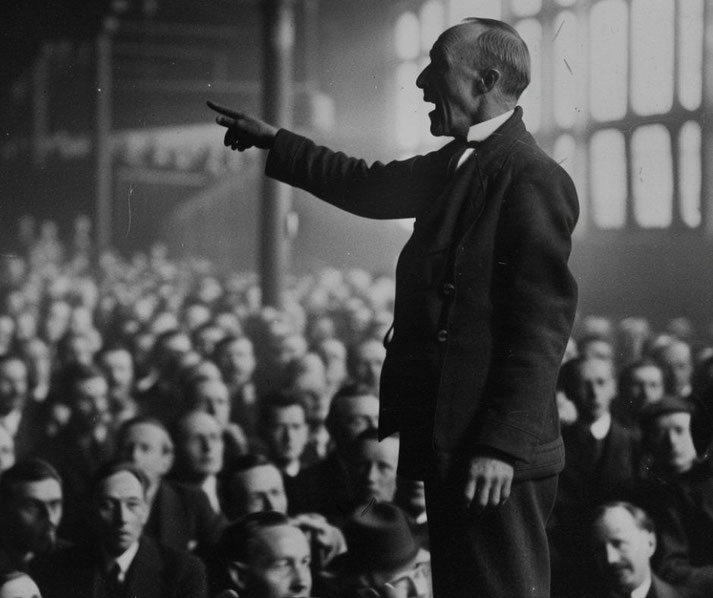

Billy Hughes

The Prime Minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923 was Billy Hughes. He was a strong advocate for conscription.

He argued that it was the duty of all Australian men to fight for their country in World War One.

At its core, Hughes believed that the war was a fight for democracy and freedom, and that it was essential that Australia do its part in defeating the Germans.

However, rather than ask his own political party to vote for conscription, Hughes sought to introduce it by using a referendum.

A referendum is a vote by the people of a country on a particular issue. Hughes knew that there was strong opposition to conscription within Australia, and he thought that it would be better to put the issue to a vote by the people.

In a speech to parliament on the 30th of August 1916, before the first referendum, Hughes said:

“To falter now is to make the great sacrifice of lives to no avail, to enable the enemy to recover himself, and, if not to defeat us, to prolong the struggle indefinitely, and thus rob the world of all hope of a lasting peace … Our national existence, our liberties, are at stake. There rests upon every man an obligation to do his duty in the spirit that befits free men.”

Hughes was not alone in his support for conscription. Many other politicians and members of the public also believed that it was essential for Australia to have a conscript army in order to win the war.

Early attitudes to the war

When World War One first broke out, there was a lot of enthusiasm among Australians for joining the war effort.

Many people believed that it was their duty to fight for their country.

Others enlisting for a variety of reasons, including patriotism, the chance to travel, adventure, and for the generous pay.

However, these attitudes changed as the war went on and it became clear that it was going to be a long and bloody conflict.

The most influential event in changing Australian attitudes towards the war was the Gallipoli campaign.

The Gallipoli campaign was a failed attempt by the Allies to capture the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey.

The campaign began in April 1915 and ended in January 1916 and more than 8000 Australian soldiers were killed or wounded during this time.

As a result, the disastrous Gallipoli campaign led to a growing disillusionment with the war among Australians.

This was reflected in the decreasing number of men who chose to enlist for military service.

Arguments against conscription

By 1916, there was also growing opposition to the war in Australia. One of the main reasons for this was the fear of being sent to fight in a foreign war.

Many Australians feared that they would be killed or wounded in battle if they were conscripted.

In addition, there was a general feeling that Australia should not be involved in a European war, as it was so far away from the conflict.

Another factor that contributed to the opposition to conscription in Australia during World War One was the perception that it would become an unfair system of recruitment.

The proposed draft process appeared to favour those who were wealthy and could afford to buy exemption from military service.

In contrast, those who were poor and would not afford to buy exemption would have no choice but to serve in the army.

As a result, this perceived inequality created a lot of resentment among the working class of the Australian population.

They felt like they would unfairly bear the brunt of deaths in war.

Also, the anti-conscriptionists also argued that there was already enough manpower in Australia to fight the war.

Consequently, there was no need to conscript more men, as they could be used in other ways, such as providing support for the war effort at home.

Finally, the Women's Peace Army, led by prominent feminist Vida Goldstein, was instrumental in the anti-conscription movement.

They were effective in organizing rallies and disseminating anti-conscription literature.

Arguments for conscription

Despite this strong opposition, a number Australians did support conscription during World War One.

They strongly believed that it was their duty to fight for their country and that conscription was necessary in order to win the war.

They argued that it was unfair that some men were able to avoid military service, while others were forced to serve.

They also believed that conscription would help to create a more unified Australian nation.

By 1916, there was a lot of division in Australia over the war. Some people supported the British Empire and wanted to fight for them, while others believed that Australia should be an independent country and stay out of the war.

It was though that conscription would have helped to overcome this division and unite Australians behind the war effort.

However, one of the most controversial aspects of the conscription debate in Australia during World War One was the religious divide.

The Catholic Church was strongly opposed to conscription, while the Protestant churches were generally in favour of it.

As is to be expected, this led to a lot of tension between Catholics and Protestants.

The first referendum

In February 1916 Hughes travelled to Europe to meet with British Prime Minister David Lloyd George.

While in Britain, Hughes learnt that the UK had already introduced conscription in January for their own armed forces, while New Zealand would do the same in June of 1916.

When he returned to Australia, he believed it was time to ask the Australian people whether they would support it as well.

When the referendum on conscription was held on the 28th of October 1916, it was narrowly defeated, with 54% of Australians voting against it.

Following the failure of the first referendum, Hughes left the Labor Party, who no longer supported him, and he formed a new political party, called the Nationalist Party of Australia.

Hughes remained as Prime Minister and tried a second time for a referendum on conscription.

The second referendum

On the 20th of December 1917, a second referendum on conscription was held.

In the lead-up to it, both sides of the debate used propaganda posters to try and persuade people to vote for their preference.

One of the most influential speakers in Australia that influenced the outcome of both referenda was Archbishop Daniel Mannix.

Mannix was the Catholic archbishop of Melbourne and he spoke out against conscription, arguing that it was wrong to force men to fight in a war they didn’t believe in.

He also argued that it was wrong to ask working-class men to fight while the wealthy class could buy their way out of service.

At the time, most Australian Catholics were of Irish descent and, as such, were predominantly from the working class.

As a result, Mannix's views received a ready audience among his congregations.

Even though he spoke on the topic only twice, Mannix’s speeches were very popular, and he managed to convince a lot of people to vote against conscription.

However, he also angered a lot of people with his speeches. Some people even called for him to be deported from Australia.

Despite the controversy, Mannix’s speeches played a major role in the outcome of the second referendum.

So, when the referendum finally occurred, once more, people voted against the idea.

This time, the margin of difference had grown, meaning that more people were voting against conscription.

As a result, Hughes never sought a third referendum on it, and conscription was never introduced in Australia during World War One.

Further reading

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.