Tiwanaku: The lost city of the Andes and its unsolved mysteries

High on the Bolivian Altiplano, the ancient ruins of Tiwanaku sit silently. This forgotten city, once the centre of a powerful pre-Inca civilisation, contains some of the most puzzling structures in South America.

For over a thousand years, it had presented archaeologists with specific unanswered questions about who had built the city and about the roles its monuments had fulfilled, and it had left open questions about the processes that led to its decline.

The mysterious location of the city

Tiwanaku occupies a high-altitude basin over 3800 metres above sea level, situated near the southern edge of Lake Titicaca.

The region is known for its thin air, harsh climate, and frequent temperature extremes, which would have posed considerable challenges to permanent settlement.

Despite these environmental limits, Tiwanaku had developed into a regional centre that supported a substantial seasonal population and managed an effective agricultural system that sustained both local communities and groups that visited.

Rather than relying on simple subsistence methods, the Tiwanaku people engineered suka kollus, raised planting platforms bordered by water channels, which helped keep the soil warmer, reduced frost damage, and allowed year-round cultivation.

These fields produced high-altitude crops such as potatoes, quinoa, and cañihua.

After they had mastered this system, they turned a hostile terrain into areas that could feed more people and support long-distance trade.

Tiwanaku's position between different environments allowed its leaders to control access to coastal, highland, and jungle goods.

Archaeologists have traced roadways, canals, and agricultural terraces across the region, all linked to the central city.

These features suggest that Tiwanaku was a political centre and also as a religious and economic hub that organised labour and movement across a wide area.

Ritual pathways and stone causeways spread out from the central ceremonial core, many of which appear to line up with solstices, lunar cycles, or other astronomical markers.

Researchers have proposed that these alignments, combined with the seasonal rise and fall of nearby Lake Titicaca, may have supported religious beliefs about fertility and the order of the world that influenced Tiwanaku society.

What do we know about the people who lived there?

The society that flourished at Tiwanaku reached its height between 600 and 900 CE, when it exerted influence across much of the southern Andes.

Archaeological finds, including ceramics, textiles, metal tools, and carved monoliths, indicate that the people who lived there maintained distinct artistic styles and religious practices.

The population likely included farmers, craftsmen, priests, and administrators, many of whom lived in residential compounds arranged according to social rank.

Elite groups inhabited the ceremonial core, where finely cut ashlar masonry and large public buildings point to a class that controlled resources and ritual authority.

Workers and traders occupied the outer zones of the city, which expanded outward in a planned fashion and reflected a high degree of social organisation.

Burial goods found in these zones varied by material and craftsmanship, which suggested clear differences in wealth and status.

Central to Tiwanaku's belief system was the so-called "Gateway God," depicted on the Gateway of the Sun with a radiating headdress and sceptres held in each hand.

Scholars have proposed that this figure was likely a proto-Viracocha deity, possibly linked to solar cycles, agricultural fertility, or divine kingship.

This figure, who appears on multiple monuments and ceramics, may have acted as a unifying symbol of state religion.

Other motifs include winged attendants, animal hybrids, and scenes of ritual sacrifice, which imply several gods and a detailed ceremonial calendar.

Excavated skeletons showed that individuals came from across the Andes. Isotopic analysis showed that some people had been born far from Tiwanaku but had been buried within the ceremonial heart of the city, which suggested they had come as pilgrims, through marriage alliances, or as part of cultural integration.

The presence of Amazonian goods, coastal shells, and highland obsidian in residential areas supports the view that Tiwanaku sustained long-distance trade networks and acted as a meeting point of different cultures.

Distinctive ritual drinking vessels known as keros, along with finely woven textiles and decorated snuff trays, were also found at the site, which reinforced the ceremonial and feasting practices that likely accompanied elite governance and religious observance.

These artefacts help reconstruct aspects of Tiwanaku's ceremonial life in the absence of written records.

What happened to the city?

Tiwanaku began to decline around 1000 CE, when its population dropped and construction halted, and as a result major ceremonial spaces were abandoned.

No written records exist to explain this shift, but physical evidence points to a period of environmental stress.

Core samples taken from nearby lake beds and ice fields revealed that a prolonged drought had affected the region between 950 and 1100 CE, which had disrupted the delicate balance of the suka kollu agricultural system.

Without sufficient water to maintain their raised fields, communities would have faced repeated crop failures, food shortages, and internal unrest.

If Tiwanaku's leadership had relied on the promise of divine favour to justify its authority, then extended droughts may have triggered a loss of confidence, which contributed to social fragmentation.

Sites that once formed part of the Tiwanaku sphere began to withdraw allegiance, establish new centres, or collapse altogether.

Looted temples, broken statues, and abandoned buildings suggested that people had dismantled or desecrated sacred sites, either as part of a rebellion or as a symbolic act during a religious shift.

There is no evidence of a foreign invasion or mass conflict, which implies that the collapse was internal and accelerated by environmental and political crises.

By the time the Inca expanded into the Lake Titicaca region in the fifteenth century, Tiwanaku had become a ruin covered by earth and grass.

Inca oral traditions described it as a sacred site of origin and linked it to their creator god Viracocha, though it is unclear whether they understood anything of the city's original builders or purpose.

The mysterious structures of Tiwanaku

Several of the stone structures at Tiwanaku are hard to explain. The Akapana Pyramid, which once rose to more than 15 metres, was built with massive stones and included an internal drainage system, though parts of the structure have undergone significant 20th-century reconstruction that may affect interpretations of its original role.

Channels inside the pyramid directed water through its core and expelled it from stone-carved animal heads, which suggested that ritual water flow was part of its role.

Excavations have uncovered ceramic offerings, animal remains, and burnt material, which point to religious ceremonies associated with fertility and the seasonal cycle.

The Kalasasaya platform was constructed from sandstone slabs and surrounded by a perimeter wall and contains astronomical alignments that track solstices and equinoxes.

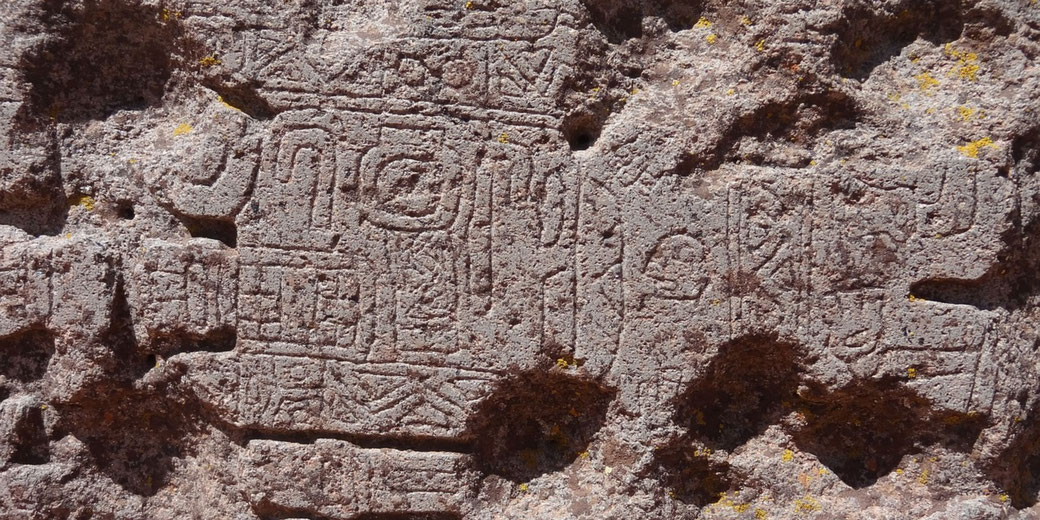

Inside this platform stands the Gateway of the Sun, a single monolith carved with symbols, deities, and solar imagery.

Researchers proposed that it may have acted as both a ritual gateway and a calendar device, though the full meaning of the glyphs remained unknown.

To the southwest lies Puma Punku, a partially collapsed temple site made from massive andesite blocks, some estimated to weigh up to 80 tonnes based on current archaeological assessments.

These stones were likely quarried from locations such as Cerro Khapia, which some researchers estimated to be over 90 kilometres away (although the exact source was debated), while red sandstone blocks came from Querimita, around 10 kilometres distant.

They were moved and cut with careful workmanship. The modular H-shaped blocks, carved with interlocking joints and right angles, fit together without mortar and suggest a good understanding of geometry and planning.

Carvings across these monuments included stylised animals, stepped motifs, and ritual scenes, yet no agreement existed on the meaning or purpose of many of these elements.

The absence of inscriptions or a writing system had left scholars to interpret the site through comparative iconography and context, and this had led to different interpretations.

What we still don't know about Tiwanaku

Despite more than a century of excavation, Tiwanaku remained one of the least understood major cities of pre-Columbian America.

The lack of inscriptions prevents archaeologists from identifying kings, rituals, or political events with certainty.

Most reconstructions rely on material culture, architectural layout, and cross-cultural comparisons with later Andean societies.

Also, the techniques used to carve and move the largest stone blocks remain unknown.

Experiments by archaeologists have tried to copy the stonework using bronze tools and wooden levers, but results have been inconsistent.

The similar stone joins and cuts at Puma Punku continue to raise questions about the tools and skills available to the builders.

Archaeologists still debate whether Tiwanaku was primarily a city, a pilgrimage site, or a ceremonial capital.

Residential zones suggest that thousands of people lived there year-round, though some researchers argue that its size and design point to occasional gatherings rather than continuous urban activity.

No large-scale cemeteries have been found near the ceremonial core of the city, which adds to the uncertainty about how the population was distributed.

The name "Tiwanaku" likely developed from later Aymara or Quechua usage and does not tell us what the original inhabitants called the city or themselves.

Oral traditions preserved by local communities provide fragments of memory, but they cannot be used to reconstruct a full picture of the culture that once ruled this high-altitude centre of stone and mystery.

Excavations continue, yet every discovery brings new puzzles, and the ancient heart of the Andes stays silent.

In recognition of its archaeological importance, UNESCO designated Tiwanaku a World Heritage Site in 2000.

Early studies by Bolivian archaeologist Carlos Ponce Sanginés and interpretations in the 20th century by Arthur Posnansky, who had argued for a construction date around 15,000 BCE based on archaeoastronomical calculations that modern archaeologists had widely discredited, had shaped debates about the site's origins and purpose.

The absence of agreement showed the difficulties of interpreting a society that had left no written records but had produced large stone works that still puzzled researchers.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.