Great Hymn to the Aten in modern English

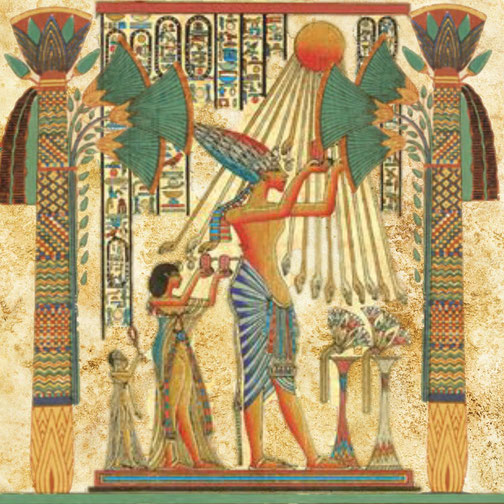

Among the most striking religious texts to survive from ancient Egypt is the Great Hymn to the Aten. It was part of the sweeping changes introduced during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten in the 14th century BCE.

His devotion to the Aten, the visible sun disk, transformed the traditional polytheistic belief system into an almost singular focus on one god.

When modern scholars eventually translated the hymn into modern English, it reads as a lyrical celebration of the sun’s life-giving power and a recognition of its hidden presence across the entire world.

What was the Great Hymn to the Aten?

The Great Hymn to the Aten, which was written in the late Eighteenth Dynasty, appeared in the tomb of the high official Ay at Amarna, the city Akhenaten.

The hymn survives as a lengthy inscription in hieroglyphs carved onto a limestone wall, which covers over 1,200 words in translation.

It presents the Aten as a universal deity whose light allows all living things to flourish and whose movements govern the natural rhythms of the world.

The hymn begins by describing the rising of the Aten at dawn and follows its arc across the sky, and it focuses on how people awaken, animals stir, and fields come to life under the sun’s influence.

By night, when the Aten disappears, the world retreats into profound stillness under enveloping darkness.

In its structure and language, the hymn abandons the traditional pantheon and emphasises the Aten’s direct connection to Akhenaten, who alone understands the god’s will.

In fact, the text is often compared to Psalm 104 from the Hebrew Bible due to thematic similarities.

Who was Akhenaten?

Before changing his name, Akhenaten ruled as Amenhotep IV, son of Pharaoh Amenhotep III and Queen Tiye.

Early in his reign, he began to favour the Aten above the other gods of the Egyptian pantheon.

Around his fifth regnal year, he ordered the construction of a new city, Akhetaten (modern Amarna), which he dedicated entirely to the Aten’s worship.

He closed temples dedicated to other gods, especially those of Amun, and erased their names from monuments and inscriptions.

Akhenaten’s reforms reached into art, which began to portray the royal family in more relaxed, naturalistic poses, and they often basked in the rays of the Aten.

The Great Hymn was part of this religious transformation. It supported the idea that Akhenaten, through his relationship with the Aten, served as an intermediary between god and people.

His revolutionary approach to theology later provoked strong reactions. After his death, traditional religion returned rapidly, and subsequent pharaohs condemned his memory.

His monuments were dismantled, and his name was omitted from king lists compiled in later periods.

The rediscovery of the hymn

Archaeologists uncovered the text of the Great Hymn to the Aten during the excavation of Amarna in the late nineteenth century.

The site had been abandoned shortly after Akhenaten’s death, which meant that many inscriptions to stay undisturbed under layers of sand and debris.

British archaeologist Flinders Petrie began early excavations at the site in the 1890s, followed by Norman de Garis Davies, who documented the tombs of Amarna’s nobles.

In Ay’s tomb, designated Amarna Tomb 25, Davies recorded the full text of the hymn.

Scholars soon saw its importance, because its considerable length and the quality of its literary and theological expression.

Modern translations aim to capture its poetic style, and they make its content accessible to contemporary readers.

Egyptologists use the hymn to explore how Akhenaten’s religious thinking diverged from tradition and how it influenced later ideas about divine authority.

As a result, the hymn is one of the most important main sources for understanding Amarna religion, royal ideology, and ancient Egyptian views on the natural world.

A new, modern English version of the hymn

We have created a new interpretation of the Great Hymn to the Aten which focuses on an easier to read text, with the natural poetry of a hymn.

It aims to express the same philosophical and theological themes, as well as trying to retain the imagery used to convey the power and glory of the Aten

We would love to hear your thoughts on our attempts.

The Great Hymn to the Aten

Oh, brilliant Aten, appearing on high, Bringer of life, adorning the sky;

Every dawn, you shine so bright, Filling every corner with your light.

Great and gracious, shining with might, your rays stretch forth, encompassing the sight;

Reaching every end of Your domain, And subduing all for Your beloved son's gain.

Though distant from us, your rays still reach, Beyond our grasp, your movements teach;

As you set, darkness covers the land, And creatures slumber, in stillness stand.

Asleep in their beds, serene and still, Each face hidden, no longer a thrill.

Your rays can't pierce, through their deep sleep, for darkness reigns, and secrets you keep.

But at Your rising, darkness does flee, your rays bring light, and set all beings free;

Two Lands in joy, with open arms, Praising Your glory, and chanting Your charms.

All creatures stir, at Your wondrous sight, Beasts in the fields, in pastures delight;

Trees and plants, all flourish and grow, Birds take flight, in Your warm glow.

Ships sail north and south, in Your wake, all paths are clear, as they make their break;

Fish dart beneath the green sea, your rays shine bright, for all to see.

You who bring forth life, in mother's womb, creating each child, a miracle to assume;

In the mother's belly, where he grows, you do sustain him, with all he knows.

Oh, how wondrous are Your creations, Hidden from man's sight in all nations;

The only god, unmatched in power and might, you shaped the world with Your own insight.

Alone, you created men and beasts of every kind, On the ground and in the sky, with a masterful mind;

From Syria to Nubia and Egypt's lands, you have set each person's place with your hands.

Their tongues, natures, and skin tone, you crafted and distinguished on Your throne;

You made a Nile in the underworld to flow, and one in heaven, so foreign lands can grow.

Cities, towns, fields, roads, and rivers, all bask in Your radiant light that shivers;

In my heart, you are enshrined, No one knows You like Your son refined,

Akhenaten, your son and heir, Well-versed in Your plans and strength to bear.

By Your hand, the world came to be, According to Your will and decree;

When You rise, life awakens, And when You set, all is taken.

You are the essence of life and breath, Through You alone, we escape death;

For You did create the earth and sky, and raised them up for Your son on high

From Your body, the King of Egypt emerged, Akhenaten, whose power surged.

And by his side, the Chief Wife so fair, Nefertiti, youthful and beyond compare;

Forever and ever, they reign supreme, In the land of Egypt, a timeless dream.

We have created a video version of this as well:

How students and teachers can use the new version

The new translation of the Great Hymn to the Aten is designed to be a helpful resource for students and teachers of ancient history and religion.

Teachers can use the hymn as a primary source to teach students about ancient Egyptian religion, language, and culture.

While, students can analyze the hymn's themes, language, and imagery to gain a deeper understanding of Akhenaten's religious beliefs and the role of the Aten in ancient Egyptian society.

If you found this interpretation useful, we would love to hear how you're using it in your classrooms.

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2025.

Contact via email

With the exception of links to external sites, some historical sources and extracts from specific publications, all content on this website is copyrighted by History Skills. This content may not be copied, republished or redistributed without written permission from the website creator. Please use the Contact page to obtain relevant permission.